New cold war in Europe as Russia turns off gas supplies

Fears of a deep chill spread across Europe yesterday after a row between Russia and Ukraine over gas prices cut supplies to the rest of the continent on a day of plummeting temperatures and heavy snowfalls.

The European Union said the situation was "completely unacceptable" as thousands of businesses were urged to switch fuels, and households struggled to keep warm in sub-zero temperatures. But there was no sign of an end to the standoff between Russia's energy monopoly Gazprom and Ukraine, locked in battle since New Year's Day.

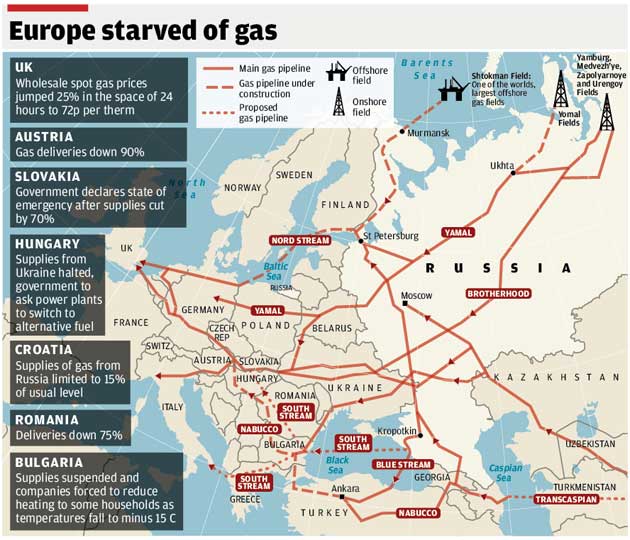

Gazprom stopped pumping gas to Ukraine for domestic consumption on 1 January after the two countries failed to agree on a fixed price for 2009. The pipelines that cross Ukraine also carry gas to Europe but that continued to flow, until Moscow accused Ukraine of siphoning off Europe's fuel and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin retaliated by ordering Gazprom to cut EU-bound exports by the amount being stolen.

Yesterday Russia stopped gas supplies through Ukraine to Bulgaria, Hungary, Greece, Turkey, Romania, Serbia, Bosnia and Macedonia. The government of Slovakia declared a national emergency; Austria and Italy reported falls of 90 per cent; France said Russian supplies had tailed off 70 per cent, and Germany also reported a decline although did not quantify it.

The Czech Republic, which took over the EU presidency this month, had sharp words for Moscow. "Drastically curbing deliveries this way is no solution to business disputes," said Alexandr Vondra, the Czech Deputy Prime Minister. "It is impossible to hold other countries hostage." He demanded the warring sides reach an agreement by the end of the week.

In Bulgaria, the government has declared a "crisis situation". The country not only has the lowest GDP per capita in the EU, but relies on Russia for all of its gas.

"Everyone was sent home from school after the gas suddenly went off," said Patrizia, an 18-year-old student in the provincial town of Pazardzhik, where the daytime temperature was minus 8C. "It's the first time I remember this happening, there was no warning, and people are worried because they have no idea how long it will last."

Douglas Erskine, a British expat, said many of Bulgaria's seven million residents would struggle. "Houses are poorly insulated, the electricity supply is unpredictable, and the elderly will struggle to get coal and wood. In many towns and villages, people gather in cafés to keep warm because they can't pay for heating at home. What will become of them if the heating goes off?"

Bakers say the price of bread could rise by 5 per cent because of gas shortages. The disruption has already forced two big fertiliser producers and a major brewery to stop production, and metals and pharmaceutical firms warned they may have to follow suit.

An EU delegation headed to Kiev for talks yesterday. Separate discussions are planned with Gazprom representatives today in Berlin.

Most European countries say they have enough gas in storage to cover at least a few weeks of disruption. The 27-nation EU gets about a quarter of its gas from Russia, of which 80 per cent is pumped through Ukraine.

Diplomatic chill: What caused it?

What sparked the gas wars?

On New Year's Eve, the deadline expired for Russia and Ukraine to agree a new contract for 2009 gas supplies. Moscow had wanted to raise its prices and charge Kiev $250 per 1,000 cubic metres, up from $179.5 last year. The Ukrainians thought that excessive and refused to pay a cent more than $201. Russia promptly put its price up to $450. Then at 10am on New Year's Day Russia's Gazprom halted supplies of all gas meant for domestic use in Ukraine.

So why are other European countries suffering?

It wasn't quite as simple as Moscow turning off the Ukraine gas tap. The EU gets about a fifth of its gas from Russia via the same pipes that pass through Ukraine. Russia cut the total volume of gas it was pumping by the amount Ukraine imports. But Russia says Ukraine stole some gas intended for Europe, and has cut deliveries by the same amount that was siphoned off.

Is this business or politics?

Russia's economy has been shaken by the credit crunch. Gazprom has debts of about $50bn and Russia's foreign reserves have dropped by more than a third, so Prime Minister Putin may be concerned about getting as much cash as possible for his gas. But the political dimension cannot be ignored given the bad blood between Kiev and Moscow. Mr Putin has not forgiven the Western-leaning President Viktor Yushchenko for sweeping to victory in the Orange Revolution in 2004, an animosity strengthened by Ukraine's ambition to join Nato and its support for Tbilisi in the Russia-Georgia war in August. Compare Ukraine with Belarus, which made supportive noises about South Ossetia and has been promised cheaper gas.

What happens next?

Kiev and Moscow need to return to the negotiating table, and with disruption starting to hit Europe, pressure for a deal is mounting. The EU is sending a mission to meet separately with Ukrainian and Russian officials, and if all else fails there could be a three-way EU gas summit. In the meantime, affected countries will have to rely on their gas stocks, which vary in size; for some, it's a matter of weeks, for others just days.

Claire Soares, Deputy Foreign Editor

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments