Nazi murder trial: Germany in one last push to bring remaining war criminals to justice before they die

After years of reluctance, Germany is moving to try the last surviving Nazi war criminals before they die. After long lives in hiding, nonagenarian Auschwitz guards and more finally face justice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

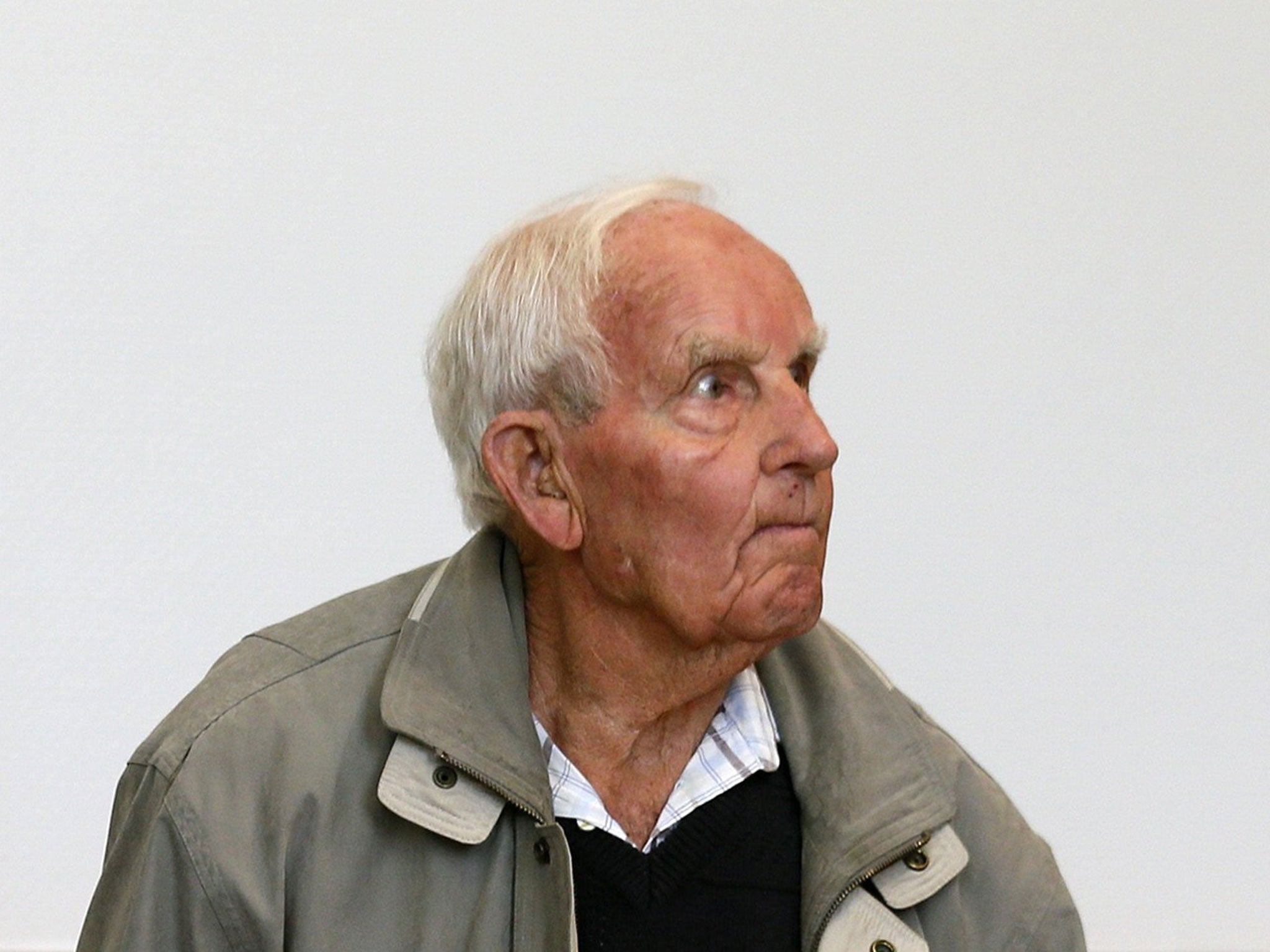

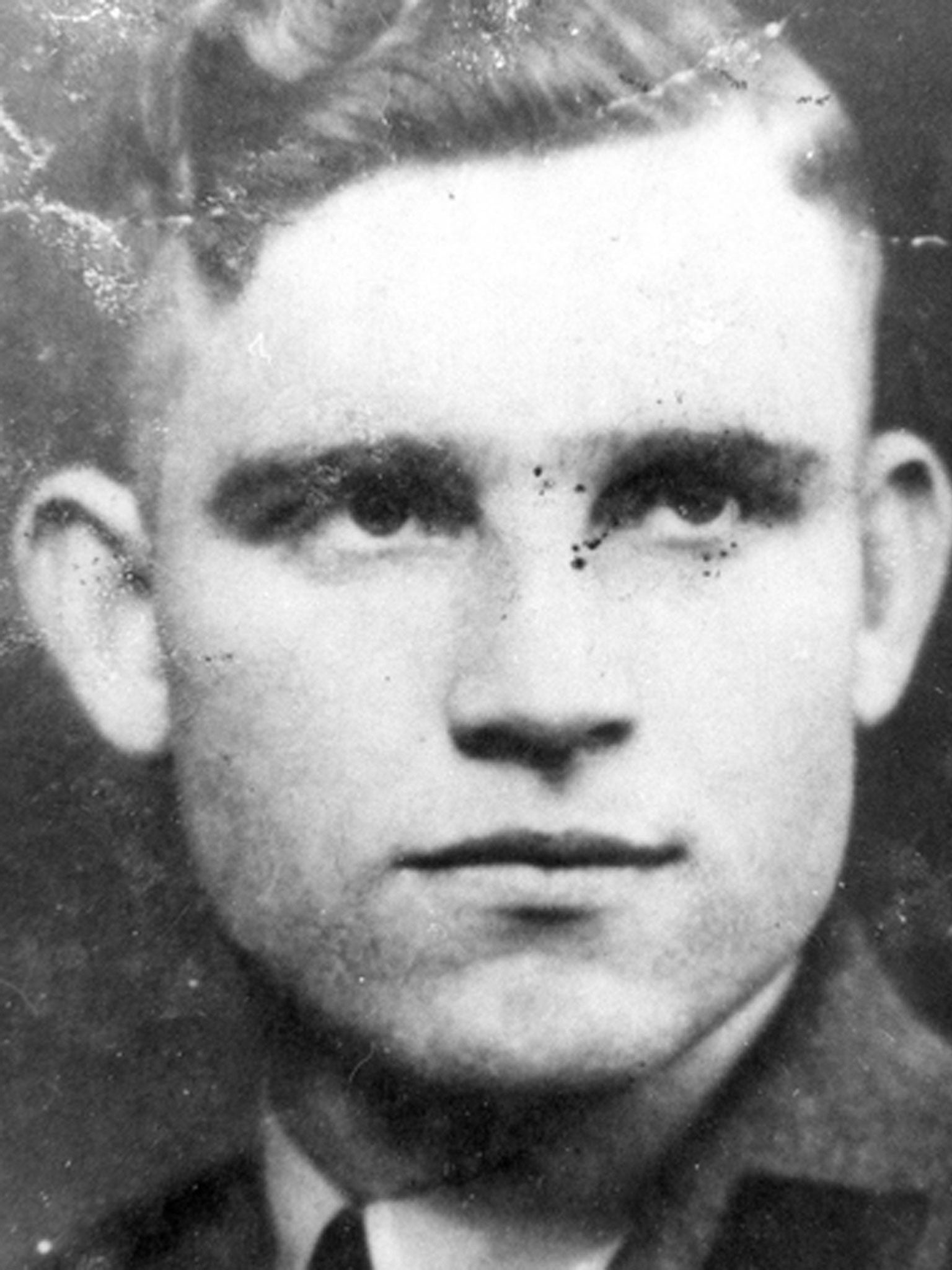

Your support makes all the difference.In Holland he is nicknamed the “Beast of Appingdam” – but white-haired, frail and aged 92, Siert Bruins hardly looked the brutal Nazi war criminal as he shuffled into a German courtroom on Monday to face charges of murdering a Dutch resistance fighter at the end of the Second World War.

In 1949, Holland sentenced the Dutch-born former Nazi SS officer to death in absentia for killing resistance fighter Aldert Klaas Dijkema in September 1944. Bruins is accused of shooting his victim four times in the back after he was captured by an SS squad near the town of Appingdam.

Yesterday, nearly 70 years after the murder, Bruins appeared for the first time in court in the town of Hagen to answer for the killing. But although he admitted joining the Waffen SS as a volunteer in 1941, he maintained a stony silence as judges read out the charges against him.

Bruins had managed to live undetected in Germany under an assumed name for 30 years. “He ran a fencing company and was a respected businessman whom people admired,” said his lawyer Klaus Peter Kniffa.

After obtaining German citizenship during the war, Bruins went to live with his family in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia after the conflict. Germany’s post-war authorities refused to extradite him to the Netherlands to serve his sentence, which was later commuted to life imprisonment, although by the 1970s he had been identified as a possible war criminal.

His appearance in court on Monday was due to a change of heart by German state prosecutors. They initially classified Bruins’ killing as manslaughter – an offence which had already passed the statute of limitations. However, they recently reassessed the case and concluded it was murder, a crime which does not become legally invalid over time.

Bruins’ case is one example of the sea change that has occurred in German justice circles over the past decade. Far from being one of Germany’s last Nazi war crimes trials, it may be the beginning of a new wave of prosecutions. The German authorities say they are poised to bring scores of other potential Third Reich war criminals to justice.

A younger generation of German judges and state prosecutors has dropped a previous reluctance to pursue Nazi war criminals and is striving to bring the few still alive to court. “There is a feeling that time is running out and that it is necessary to pursue the last war criminals before they die,” Efraim Zuroff, the chief Nazi hunter of the Jerusalem-based Simon Wiesenthal Centre – which in 2002 launched Operation Last Chance , a mission to track down ex-Nazis still in hiding – told The Independent yesterday.

Most of the top Nazi war criminals such as Adolf Eichmann have either been brought to justice or, as in the case of the infamous Nazi death camp doctor Josef Mengele, escaped by emigrating and living a life on the run. There is only a handful of top Nazis unaccounted for and most are presumed dead.

But in July the Wiesenthal Center launched a poster campaign in Germany displaying the entrance to the infamous Auschwitz death camp. The initiative aims to bring the estimated 60 lower-ranking Nazi war crimes suspects now living in the country to trial. Mr Zuroff said yesterday that the campaign had resulted in a “deluge” of emails from Germans who claimed to have information about war criminals.

The campaign follows the highly publicised trial of the Ukrainian-born former Sobibor death camp guard John Demjanjuk following his extradition to Germany from the US in 2010.

Demjanjuk was convicted of war crimes by a Munich court in 2011. He was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment on charges based solely on records showing that he served in the camp where 28,000 Dutch Jews were sent to the gas chambers on arrival. There were no witnesses who identified him as a camp guard.

Demjanjuk died last year at the age of 91. But his trial created a legal precedent in Germany which enables prosecutors to bring other former camp guards to trial simply on the basis of Nazi records. Last month Germany’s Central Office for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes announced that as a result of the Demjanjuk trial, it was ready to begin issuing arrest warrants for 40 men and six women suspected of having worked as guards at Auschwitz.

Kurt Schrimm, the organisation’s director, said his agency planned to recommend that state prosecutors bring charges against most of the 46. All the women under investigation were said to have been SS guards in the women’s section of Auschwitz. The youngest is 87. “We do not know of any executions committed by female guards but some treated prisoners very brutally and have already been convicted of war crimes,” Mr Schrimm said. His office has refused to name any of the suspected war criminals likely to be charged but one of the first to be indicted is expected to be the former Nazi SS Auschwitz guard, Hans Lipschis, who was recently tracked down by a German newspaper in a retirement home near Stuttgart.

Lipschis, who is 93, was born in Lithuania in 1919 and granted ethnic German status in 1943 following the Nazi invasion of the country. He is accused of working as a guard at Auschwitz from 1941 until 1945 and of participating in murder and genocide. He fled to the US after the war and lived in Chicago for 26 years before he was exposed. The authorities deported him to Germany for lying about his past to obtain a residence permit.

But once back in Germany, the authorities concluded that they had no evidence on which to prosecute Lipschis. Subsequent paperwork has since surfaced which showed that he was a member of an SS “Death’s Head” unit which, among other duties, supervised the unloading of trains carrying Europe’s doomed to Auschwitz. He denies involvement in the mass murder of Jews at Auschwitz and claims he was merely a cook at the death camp.

Given the new legal precedent set by the Demjanjuk case, Lipschis is unlikely to escape trial this time around. But Mr Zuroff argues that the final decision will be down to Germany’s state prosecutors and whether they opt to bring charges. He added: “We welcome the move, but Germany is legally a de-centralised country. It is up to individual state prosecutors. More may be pressing charges against war crimes suspects but some still don’t care.”

Trials pending: Nazi war criminals

Alois Brunner commanded the Drancy internment camp outside Paris and was responsible for the deportation of over 140,000 Jews. He fled to Syria after the war and is thought to have been living there ever since.

Aribert Heim was a doctor at the Mauthausen Nazi concentration camp who tortured and killed hundreds of inmates. He was tracked down in 1962 but then fled West Germany.

Gerhard Sommer – a second lieutenant in the Nazi SS, he was convicted by an Italian court in 2005 of “murder and special cruelty”, but Germany has refused to extradite the 94-year-old to Italy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments