Mustafa the movie divides Turkey with a portrait of the 'real' Ataturk

National hero depictedas solitary hard drinker by documentary-maker

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Turks venerate Ataturk, the founder of the republic and architect of arguably the most successful social modernisation programme of the 20th century. How much they really want to know him is questionable, however, judging from the furore that has erupted since a new documentary on his life was released in cinemas last week.

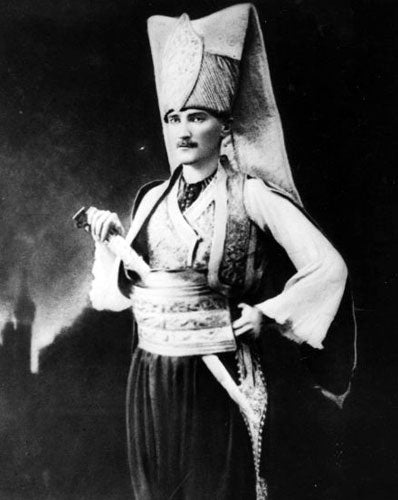

Directed by Can Dundar, a leading documentary-maker with an until now spotless secularist record, Mustafa is the first Turkish film to emphasise the private side of the man whose stern features preside over public buildings across the country. The documentary, which carries Ataturk's childhood name, breaks no taboos but presents Ataturk as a hard-living, hard-drinking and ultimately rather melancholy man who felt increasingly detached from the country he created. "Remember me," is scrawled in the margins of one of his last public speeches.

"I wanted to present Mustafa Kemal in a more intimate, affectionate light," Dundar said in a telephone interview. "All those statues, busts and flags have created a chief devoid of human qualities." Watched by 470,000 people in its first five days in cinemas, his film has been widely praised. The director and film crew received a standing ovation at its gala screening. But it has also attracted furious criticism.

"Ataturk raised up a people about to be excised from world history, and here he is presented as a drunken debaucher," said Israfil Kumbasar, columnist for Yeni Cag, an ultra-nationalist daily. "Would you accept such a portrait of Churchill?"

Some radical secularists go further, seeing the film as part of a Western-backed plot to weaken Turkey's Kemalist army – the chief obstacle to alleged plans to dump secularism in favour of "enlightened Islam". The United States, "treated our soldiers like common criminals in Iraq", says Yigit Bulut, a popular columnist in the secularist daily Vatan, referring to the 2003 arrest of Turkish troops that came close to destroying relations with the US. "This film is part of the same strategy."

Bulut concluded his column last Friday by begging readers: "Do not watch this documentary, dissuade others from watching it, but above all do not allow it to plant seeds belittling Ataturk in your children's minds."

In a quirky twist yesterday, two doctors announced they were taking the film to court for repeatedly showing scenes of Ataturk smoking cigarettes. "Ataturk is a national idol," said Orhan Kural. "Statements like 'Ataturk used to smoke three and a half packets of cigarettes a day'... harm his image and are illegal. We were left wondering whether it wasn't an advert for smoking."

The attacks seem to be having their effect. Watching Dundar's last Ataturk film has become a rite of passage for Turkish primary schoolchildren since it was released in 1993. Teachers seem to be more wary of taking their charges to watch Mustafa. "My son's class was supposed to go and watch it on Monday," said Rusen Cakir, a leading journalist. "But the trip was cancelled. They worried the film might not be ideologically suitable."

Such reactions are not surprising. As the film points out, the first steps to create a personality cult around Ataturk began in his lifetime, with statues erected in Turkey's three largest cities. After his death in 1938, and particularly after the 1980 military coup, the process accelerated.

A residue of the most brutal of Turkey's three military interventions, the country's current constitution enthrones Kemalism as the country's official ideology. Another remnant of 1980, requires university students to be raised, "devoted to Ataturk's nationalism ... revolutionary reforms and principles". Insulting Ataturk is acriminal offence.

Dundar thinks critics are missing the point. "My son is now reciting the same poems about Ataturk that I and my father recited when we were at school," he said. "The younger generation has reached saturation point. For young people, Ataturk has become a source of derision." A historian specialising in the early years of the Turkish Republic, Ayhan Aktar agrees. "The 1980 junta used Ataturk as a club to beat the Turkish people with – no wonder many are disgusted," he said. "Dundar's documentary has given Kemalism the kiss of life."

Opinion is divided as to how the Mustafa effect will pan out. Some think Dundar's prestige among secularist Turks may have imbued his vision of Ataturk with the force to begin a proper debate. Like Dundar, they think the time has come to publish the diaries and letters kept out of public view in military and civilian archives.

"It is a crime not to let people know how Mustafa Kemal explained himself," said Ipek Calislar, who was acquitted in 2006 of insulting Ataturk in the biography she wrote about his wife.

"Loving people when you have no means of understanding them is very stupid."

But she expresses deep concern at the way debates are developing over the documentary. "People are so angry, it's frightening," she said. "This is not an atmosphere conducive to reasoned debate."

Ataturk: A brief biography

* Mustafa Kemal Ataturk (1881-1938) was the founder of the Republic of Turkey. He received the name Atatürk (Father of the Turks) in 1934 from the Grand National Assembly as a tribute.

* He was born in Salonika, modern-day Thessaloniki.

* Ataturk opposed the conservative forces around the sultan. He believed Turkey's only chance of survival was to adopt European democratic principles.

* After the abdication of the sultan and the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey 1923, Ataturk was named president. His reforms included introducing Western law codes, dress, and calendar, the Latin alphabet and, in 1928, removing the constitutional provision naming Islam as the state religion.

* He founded the People's Party (renamed Republican People's Party in 1924) in August 1923 and established a single-party regime which, except for two brief experiments (1924-1925 and 1930) with opposition parties, lasted until 1945.

* Ataturk died in Istanbul on 10 November 1938.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments