Kurds who became 'village guards' and fought PKK rebels in Turkey to be disbanded – but they fear a betrayal

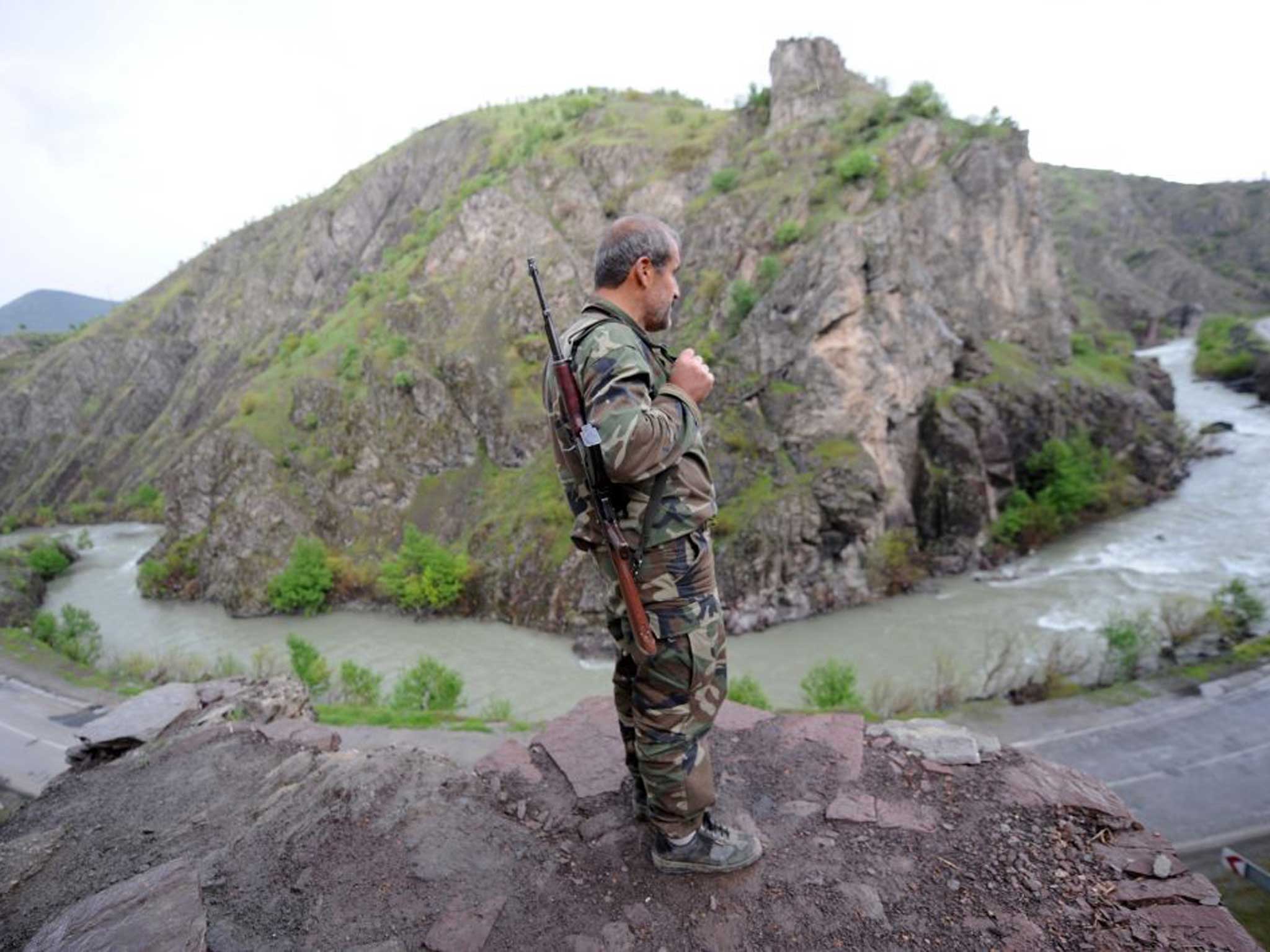

Tens of thousands, often under heavy state pressure, accepted the Kalashnikovs and started fighting against their own people

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dressed immaculately in a dark blue suit and with his hair perfectly combed, Seymus Akbulut was sitting in front of a portrait of Kemal Ataturk, Turkey's founding father, and a huge Turkish flag. On his desk were two more Ataturks: one on a silver plate, one a glass statuette in a red velvet box. "We love Ataturk," he said. "Whatever the state wants us to do, we do it."

Mr Akbulut, from the south-eastern town of Midyat, is one of many Kurds who in the early 1990s were branded traitors when the conflict between the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which wanted to carve out an independent Kurdistan, and the Turkish army was getting more violent every day.

The state needed helpers, and in the late 1980s started to set up the so called "village guard" system: citizens were given a weapon and a salary to help fight the PKK. Mr Akbulut, who became a village guard in 1992, was one of tens of thousands of Kurds who, sometimes voluntarily but mostly under heavy state pressure, accepted the Kalashnikovs and started fighting against their own people.

The system kept growing, and currently there are some 80,000 village guards in Turkey's southeast. Most of them earn about 900 Turkish lira (£235) per month, others get only the weapon and no salary.

Now in his late fifties, Mr Akbulut is head of an association of village guards that advocates their rights and supports the families of guards who died in the conflict. "Before, I worked in tourism," he said. "I made more money in a week than as a village guard in a month, but I did it willingly. We had to defend our lands. Nobody but the state can control our lands."

However, the end of the village guard system is approaching – at least if the peace process in Turkey continues. Almost a year ago, the PKK leader, Abdullah Ocalan, announced that the group would withdraw from Turkey. "We have now reached the point where weapons must be silent," he said.

The withdrawal had, by all accounts, been very well prepared. Turkish authorities for the first time admitted talking directly to Mr Ocalan, who is serving a life sentence in prison for high treason. And the development now means that the village guards must be disarmed.

Nesrin Ucarlar, a political scientist at Bilgi University in Istanbul who investigated the system, said: "Such a system has no place in a democracy."

But disarming the guards will not be an easy matter, Ms Ucarlar said, adding that the system had penetrated every layer of society in the region.

"In the past, many political parties have vowed to abolish the system if they came to power, but nobody did," she said. "They need it. The guards don't want to give up their arms without the PKK doing the same."

There is also the not insignificant matter of finding alternative employment for thousands of people in a region that already has a high unemployment rate.

"It needs a comprehensive plan to abolish the system," Ms Ucarlar said. "But the state is not working on it. It has even employed more village guards since the peace process started."

In Midyat, Mr Akbulut told The Independent on Sunday that he was not intending to give up his weapons easily. "I will not turn in my weapon until there is real peace," he said. "Peace for everybody."

In a small building which serves as the guards' headquarters, many said they were scared of what might happen to them if they disarmed.

"We want peace, but we want to be safe too," said one guard in his fifties who was unwilling to provide his name. "What if anybody wants to take revenge on us? We have to keep our weapons to be able to defend ourselves."

Ms Ucarlar says the fear is probably without foundation: "The PKK has been very harsh against village guards, but that is over now. It became more realistic and I don't think there is any danger. But their fears should be taken seriously." However, the village guards in Midyat do not trust the PKK. The head guard compared the state and the PKK to a father and son: "Imagine you have a child, and you take good care of him, you educate and feed him. And then, when he grows up, he betrays you by turning against you. That is unacceptable, right?"

Kurds who refused to become village guards often paid for it by having their villages burnt down in the 1990s and were forced to migrate to the cities.

Those who were pressured into the group despise the guards who took up the state's weapons willingly. They see them as traitors to the Kurdish cause of greater political and cultural rights. But Mr Akbulut and his men dismiss that criticism: "It is a lie," they say.

"There is no suppression of Kurds," Mr Akbulut adds. "Father State has always been good to us."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments