'It was like a science-fiction movie': Chernobyl - site of the world’s worst nuclear accident revisited

A massive £1.2bn civil engineering operation is hoping to make Ukrainian site safe, but it is running a decade behind schedule and there are doubts whether it will ever be finished

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ever since he risked his life to fight the nuclear fires at Chernobyl, Anatoli Gubariev has dreaded a new catastrophe in the ruins of reactor No 4.

Hundreds of tons of radioactive dust and fuel are still buried there, covered with an edifice of concrete slabs and metal plates called the object shelter. It was hurriedly erected after the accident, and parts of the old reactor covering are now starting to collapse.

The worst recent incident was a radiation alert when the roof of the turbine hall fell in, forcing terrified workers to put on respirators and flee the site – and giving Ukrainians a nasty reminder that their Chernobyl problem has not gone away.

The solution, a gigantic £1.2bn metal shell called the Arch, is finally taking shape in a safe zone, 300m away from the reactor’s intense radiation. A stupendous feat of engineering, already taller at its highest point than the Statue of Liberty and wider at its base than a football pitch is long, the Arch is the gleaming creation of Western corporations, paid for by the G8 nations. One day its 15,000-ton weight will slide on specially laid tracks into place over the reactor, hermetically sealing it off.

But it is nearly a decade behind schedule, construction has not yet reached the half-way stage, and there are growing doubts about when it will finally be completed. “We want this Arch finished so Chernobyl is safe once and for all,” said Mr Gubariev, 52, head of an organisation for veterans of the accident in the industrial city of Kharkov.

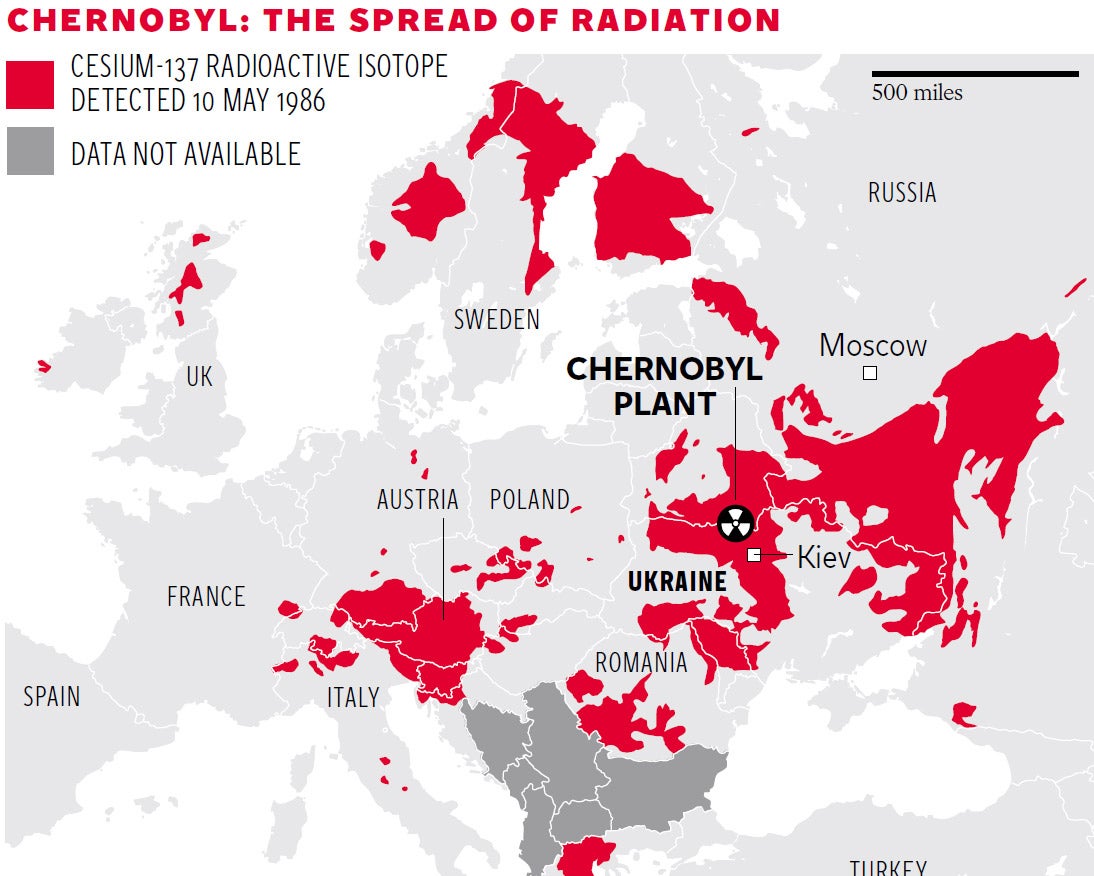

He has good reason to fear Chernobyl: he watched comrades die of acute radiation sickness, and in 1991 he survived cancer. A radioactive cloud sent blowing across Europe after the reactor exploded in 1986 has been blamed for an estimated 6,000 cases of cancer.

“Construction has been so slow, and we are getting worried by the state of the shelter that covers the reactor,” Mr Gubariev said. “Ukrainians are starting to ask will they ever finish the Arch? And in particular will it be ready before the shelter falls down and causes a second Chernobyl disaster?” The project to make Chernobyl safe matters to the people of the Ukraine – who are still at risk from its radioactive contents – and to the international nuclear industry, which is enjoying an unexpected renaissance in an energy-hungry world.

The disaster at Chernobyl made the nuclear industry look risky and expensive, and gave massive impetus to anti-nuclear movements around the world. The public relations damage of Chernobyl can never be undone, but the nuclear industry is keen to ensure that the Arch, when it is finished, will be a gleaming, spectacular new symbol of how technology can make even the worst nuclear mess safe.

Standing underneath the half-built Arch, which now dominates Chernobyl’s industrial skyline of crumbling power stations and rusting cranes, the foreign engineers who direct the project are hugely proud of their creation.

“Nothing like this has ever been attempted before,” said Don Kelly, 57, a nuclear industry veteran from Washington State, as he strained to look far overhead where Turkish steeplejacks wearing harnesses were fixing metal panels. “For all of us here this is the most exciting project you could wish to work on.”

The project is a latter-day Tower of Babel, with specialists from 24 nations. To enter the complex, ringed with razor wire, they have to show their passports to armed police, on guard against the dangers of terrorists breaking in. The reactor is full of raw material for a dirty bomb.

On another part of the huge structure, cranes were lifting 30 ton sections into place. “How do you like our little Meccano set?” joked David Driscoll, 65, an engineer from Manchester who worked for years in the offshore oil industry.They were standing in a decontaminated zone, where radiation levels are low enough for no protection to be needed, although a dosimeter and emergency breathing equipment must be carried at all times.

Other parts of the site are less benign. Only a couple of hundred yards away, next to the reactor, was the alarming sight of diggers being driven by men wearing the kind of white suits you might expect to see at an accident site, respirators clamped over their mouths.

They are working on what is basically a radioactive building site, which managers say explains the slow pace of work – they hope the Arch may be completed in 2015. Everything at Chernobyl is at least mildly radioactive, including the packs of stray dogs that live close by. Ukrainian labourers feed and stroke them, but foreign experts shun them.

Despite the problems, there have been no serious radiation accidents and in recent years only three Ukrainian workers have registered unusually high levels: two from eating mushrooms picked in nearby woods, and one from eating fish from Chernobyl’s cooling pond. Workers have a bad habit of taking an early morning slug of vodka before heading to work: there is a Ukrainian folk belief that it protects against radiation. Dozens have been dismissed for failing routine breathalyser tests.

Every stage of the project has been painstaking and potentially dangerous. Dismantling the reactor chimney, one of the trickiest jobs, is due to commence this month and must be finished before the onset of Ukraine’s ferocious winter when temperatures reach -25C. Chimney sections weighing up to 55 tons each, full of radioactive soot and dust, will be cut off with a plasma cutter by teams of two men and removed by crane. Lifting out the sections will be nerve-racking: if a crane fails, or an operator miscalculates, and a section falls into the reactor, a new cloud of radioactive dust could be released into the atmosphere.

The problem of dismantling and removing the reactor and its dangerous contents are the reason for the huge size of the Arch; it must accommodate giant cranes in a sealed area, where work can be done without radioactive dust getting out.

However, Philippe Casse, 61, the site manager, who has worked on the project since 1998, admitted that even after the Arch is finished, it may still be decades before the mess inside can finally be removed. “There is no money at the moment,” he said. “Perhaps it can be done in 50 years when the right technology is developed.”

Video shot inside the highly radioactive reactor building by Alexander Kupny, a senior technician for 21 years, shows why disposing of Chernobyl’s deadly contents will be so difficult. Until he retired in 2009 Mr Kupny, 53, was a so-called “stalker”, one of the technicians who risked trips inside the building to monitor its condition. He went inside 10 times, and his experiences have given him a poetic outlook on reactor No 4. “To me the reactor is almost like a living thing, like a beast that is sleeping,” he said.

His film showed wrecked machinery and “lava flows” of burnt fuel, a terrific mess which can only be accessed through a maze of corridors where no robot can go. “It’s like a science-fiction movie in there,” he said, looking up from his computer screen and grinning.

Mr Kupny has become one of the most outspoken critics of the slow-moving Arch project. Ukrainians listen to him because his family is a Chernobyl dynasty: his father was a director of the complex after the accident, and three years ago his son started work there.

“It is the first time anything like this has been done and the project is hugely complex,” he said at his home in Slavutich, a new town built for the engineers and their families after the disaster irradiated their old homes next to the site.

“I hope it works, but in my opinion there is only an 80 per cent chance of getting the Arch into place, perhaps by 2018. Whatever managers say I doubt it can be done before that.”

He fears the Arch’s 15,000-ton weight may be nudged off course as it is slid into place, and may even crash into the reactor building. The discovery of massive underground pipes buried under the route has given engineers a new difficulty, he said. Until the Arch is finished, the only thing containing the radiation within is the increasingly decrepit object shelter.

But he believes the biggest flaw in the project is the lack of a plan to permanently dispose of the radioactive material inside the reactor.

“There is no plan for that, no money, and no nuclear waste dump in the Ukraine to put it in anyway. The Arch will look fantastic for sure, and we need to cover that reactor. But even when it is finished, for the Ukraine it won’t be the end of the Chernobyl nuclear headache.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments