Intimate diaries and banal letters live on in France's library of secrets

Archive of unpublished biographies and scrapbooks dates back to 19th century

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Everyone's life is a novel, which has not yet been written. Or in some cases, it has been written but never published.

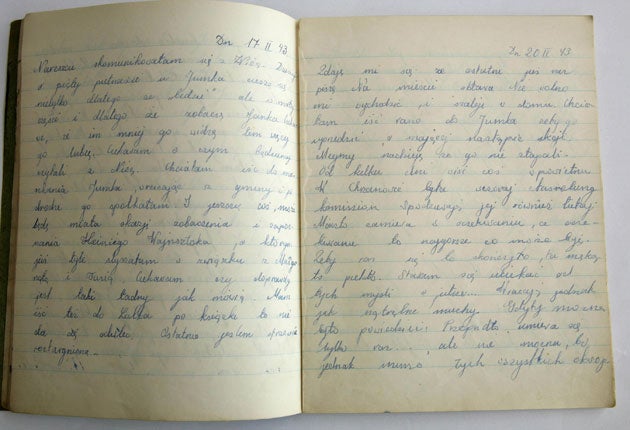

In a small town in eastern France, there is a library, or archive, of intimate secrets: a collection of 2,500 unpublished – and mostly unpublishable – autobiographies, diaries, scrapbooks, bundles of letters and collections of emails dating from the early 19th century to last month.

"There are as many diarists as there are amateur pianists. They just make less noise," says Michel Vannet, custodian of the archive at Ambérieu-en-Bugey, near Lyons.

The man who co-founded the association, which snaps up these previously unconsidered literary treasures, Philippe Lejeune, puts it another way.

"There are no limits to literature," he says, "it can turn up anywhere."

Similar archives of unpublished "autobiography" exist in other countries, including Britain (at the University of Sussex). There is a library, in Burlington, Vermont, which offers a home to unpublished books of all kinds.

What makes the Ambérieu archive unique is that it is not just an archive. It is also a kind of intimate "book club" – everything received is read by volunteers and a one-page "review" published in the association's journal. However, contributors can ask for their secrets to be hidden until their death or locked away until an agreed date in a "cupboard of secrets". Inclusion in the Ambérieu archive guarantees simply that their writings, and their life's story, will not die.

The closed archive contains a large, brown envelope which was deposited recently by an old woman with failing eyesight. In a covering letter, she wrote: "I don't want you to read my diary because it will not contribute to public understanding. It is only a banal story of adultery ... Until now I have destroyed all my writings... I felt the death of my words like a series of small suicides."

The contents of the "open" archive range from a single, autobiographical poem, written in alexandrines, to a diary consisting of 65 200-page notebooks, delivered in a trunk. There are moving autobiographies of wartime, banal descriptions of the working life of postmen or plumbers, surreal scrapbooks of personal mementoes and a small sack of rose petals grown in the compost of a burned diary of "personal suffering".

One woman sent a bundle of printed-out emails which she had sent to her friends when she thought she was dying of cancer. Someone tried to bequeath their furniture, claiming it represented his life. This was refused (for lack of room) but photographs of lovingly-assembled interiors are accepted.

After 16 years of existence, the Ambérieu library of secrets is proving to be a goldmine for researchers. A book appears this month by the historian Anne-Claire Rebreyent, Intimités Amoureuses. France 1920-1975, which charts changing French attitudes to love. Mme Rebreyent researched the book entirely in five years that she spent visiting the Ambérieu archive.

Some of the material consists of diaries or letters found in attics or antique shops. About 80 per cent was sent in by the authors or their children. Some "living" diarists are permitted to send an update every year.

More women contribute than men. Three-quarters of the texts are autobiographies, 20 per cent are diaries and five per cent are letters. The archive is the work of the Association pour L'Autobiographie et le Patrimoine Autobiographique (APA), founded in 1992 by Philippe Lejeune and Chantal Chaveyriat-Dumoulin,

M. Lejeune is France's best-known academic specialist on autobiography, sometimes known as the "pope of autobiography". Much of what is preserved at Ambérieu would fail the usual tests of literary merit or publishability, he says. But the texts have other qualities – of authenticity, of freshness, of originality of voice – which are not always found in officially recognised literature.

"The aim of an autobiography is not to be good but to be true – which it rarely fails to be," M. Lejeune said.

No attempt is made to try to identify publishable work. Nothing is refused.

"We don't want to establish a hierarchy among texts, but to give each of them a chance of being read," M. Lejeune says. "Our ambition is to establish a system of 'micro-reading'. Our aim is not for three or four texts to be read by a thousand people, but for a thousand texts to be read by three or four people."

The 800 members of the association, who pay €38 (£34) a year, are split into half a dozen study groups. Each new entry to the archive is taken on by one reader, who writes a review published in the association's twice-year Gardé-Memoire or memory safe. This acts as a kind of index.

Some insufferable texts are never read again. Writings which receive glowing reviews are passed around and discussed. Some – the "best-sellers" – end up being read by everyone in the association (many of whom are diarists themselves).

M. Vannet, director of the mediatheque which houses the archive, says: "We are a club of strangers that you meet on trains – the kind that want to tell you their life story."

Hidden gems: A homage to melancholy

One of the oldest texts in the "archive of autobiography" at Ambérieu is a classic piece of early 19th-century melancholic romanticism by Victor Audouin, an obscure Parisian medical student. His diary was found in an antique shop: "I went to the Jardin du Luxembourg. The weather was magnificent. I found that I could not think. No idea presented itself to my imagination, which had been so lively a moment before. A melancholy, which was not without charm, captivated me entirely... Tears ran down my cheeks, which had no cause in my thoughts and which no amount of reasoning could halt. Finally, seven o' clock came and the [park] drum woke me from this strange ecstasy. I walked home."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments