Identified at last: faces of the Somme

One by one, the stories behind a wartime photographic archive are being unearthed. John Lichfield reports on a unique project

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Almost 95 years after the battle of the Somme, a French photographer's long lost snap of a British soldier has finally reached his grandson, via The Independent and the internet.

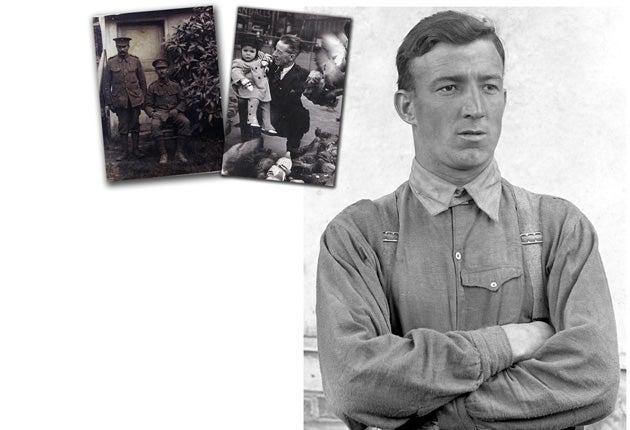

The soldier, Walter Wheeler from south-east London, is the third of more than 400 "lost" images of British and Empire soldiers – salvaged from rubbish skips in France and published by The Independent – to be recognised by surviving family members.

Captain Wheeler, who was a sergeant in the Middlesex Regiment at the time of his shirt-sleeved photograph in 1916, went on to have a long and eventful life. He turned down a nomination for the Victoria Cross in 1917 but won a George Medal for defusing an unexploded German bomb near Goldsmith's College, New Cross, during the Blitz in 1941.

"I am convinced that it is my granddad," said Michael Jago, 64, a retired magazine publisher living in Chicago. "There is something about that nose and that determined look. It could only be him."

The Somme photographs – newly discovered glass negatives of Tommies, Aussies and Canadians and French civilians of the period 1915-16 – have generated extraordinary interest all over the world. The first batch of 400 was published in The Independent Magazine and on independent.co.uk in May 2009 and a second batch of 40 in May this year.

The photographs, preserved on 9 x 12cm glass plates, lay undisturbed for nine decades in the attic of a ramshackle barn near Warloy-Baillon, 10 miles behind the British lines on the Somme. When the barn was restored in 2007, the photographic plates were thrown into a rubbish skip. Passers-by rescued some. Many others may have been destroyed.

First World War graveyards and memorials are a legion of names without faces. The lost Somme photographs have given us, movingly, hundreds of faces without names.

They have since consistently been among the most visited items on The Independent's website. The first set of images has now been viewed more than 3.6 million times. The second batch has attracted 314,000 views since May.

A photograph has come to light in Britain in recent weeks which appears to confirm a theory about their origins. Many of the images show soldiers, in ones or twos or small groups, posed against the background of a battered door in the garden of what is probably a farm house. It was assumed that they were originally taken, for a small fee, by a local amateur photographer as "souvenir snaps" to be sent by soldiers to loved ones at home.

Emma May Smith from Brigg in Lincolnshire has now sent us a picture of her grandfather, George Wilfred Smith, standing in front of what is, without doubt, the same battered door, in the same house in the same village in the Somme. This is the first picture to turn up in Britain which matches the "lost" Somme snaps.

"The photograph had been handed down in another part of our family and we first saw it seven years ago," said Ms Smith, 28, a politics student at Sheffield University. "My grandfather must presumably have sent it to his own father. My dad recognised him almost immediately."

The sitting soldier in the photograph is unknown. The standing soldier, George Smith, was born in Ashby, Lincolnshire, in 1886 and conscripted in early 1916, when he was 29. He died in 1986.

Many of the images are believed to have been taken close to a clearance hospital at Warloy-Baillon, before and during the first battle of the Somme, in July to November 1916.

The historical value of the plates, as a record of the British Army during the bloodiest battle in its history, was first grasped by two local men: Bernard Gardin, a photography enthusiast, and Dominique Zanardi, proprietor of the "Tommy" cafe in Pozières in the heart of the Somme battlefields.

In 2008, Mr Gardin, 62, an amateur photographic historian, was given a batch of 270 of the glass plates by someone who knew of his hobby. Others were acquired by Mr Zanardi, 49, who has a museum and collection of Great War memorabilia at his café.

The two men combined to process the images at their own expense. Publicity turned up another 40 plates this year. Until now, only two of the soldiers have been identified. Jim Mundell from Dumfriesshire has been recognised by descendants as sitting among a large group of gunners in a photo in the first batch. He survived the war to become a farmer and died in 1955, aged 59. A kilted Scottish soldier, shown in two of the images in the more recent batch, has been identified as James Henry Hepburn of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. He died in 1962, aged 64.

To them can now be added Walter Wheeler of the 1st Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, shown here in his "lost Somme photograph" but also in a later snap holding his grandson Michael, two, in Trafalgar Square in 1948. Mr Wheeler died in 1978, aged 91. He worked as a council stores manager until the age of 80.

"I can only assume that this photograph of him taken on the Somme was intended to be sent home to his family," Mr Jago said. "Whether it ever arrived, I have no idea. But you could say that it did finally arrive when I recognised it on The Independent's site the other day."

He added: "I was very close to my grandfather, who was an extraordinary man. He volunteered in 1914 and went right through the war. He once told me that his commanding officer offered to nominate him for a VC after he rescued a wounded officer in 1917. Granddad refused. The officer wanted to know why. Granddad replied: 'Because, sah, as a VC, sah, I would have to be the first person over the top every time, sah. I wouldn't last a week, sah'."

Nonetheless, Walter Wheeler was given a battlefield commission for valour late in 1917 and was later promoted to captain. As a working-class Cockney boy, he told his grandson later, he was given a "miserable time" as an officer, not by the enemy but by the snobbery of British officers.

For the full set of lost Somme photos, see http://ind.pn/glFkc2 and http://ind.pn/hifXCx

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments