Greece debt crisis referendum: Greeks want to vote No to austerity – but Yes to Europe

The country’s potential exit from the euro weighs heavily on Greeks' minds

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It wasn’t until Saturday, six days after Greece’s forced bank holiday began, that the anxiety in the queues outside Athen’s ATMs became palpable. Greeks, anxiously awaiting today’s referendum – which could decide their future in the eurozone – began to feel the real pressure on their wallets.

“This is just crazy,” said an exasperated young writer abandoning a 50ft queue in the neighbourhood of Pangrati. “Every day we wait to get a measly €60 [£43] allowance. I’m fed up. What if there’s an emergency – what are we to do then? This government is useless.”

Anthee, who refused to give her last name, said she had supported the coalition government, but that Syriza’s grace period was now over. The referendum will be a verdict on Alexis Tsipras’s young left-wing, coalition government as much as on the question on the ballot – whether to accept the creditors’ bailout proposal, which includes further tax rises and cuts.

In Pangrati, Anthee said she would decide how to vote when she gets to the ballot box, with the country’s potential exit from the euro weighing heavily on her mind.

She is unlikely to be alone. More than 10 per cent of voters were still undecided by Friday, according to polls. Many Greeks feel they are between a rock and a hard place: they want to vote No to austerity but Yes to Europe. Divided over the referendum, they are united in their desire to stay in the common currency. In the last published poll, only 15 per cent of Greeks want a return to the drachma.

“I want my pride and my country’s independence back, so I’m tempted to vote No or just abstain,” said Anna Bravakou, a pensioner. “But will that bring back my dignity? I doubt it.”

Voters were travelling back to their home districts to cast their votes. But for some, including Eleni Christodoulou, a shopkeeper, even voting was an economic burden; tickets to her home in the southern island of Samos, where she was born, were prohibitively expensive.

“On the one hand I’m relieved, because I’m torn over what to vote, but on the other hand I’m angered by being prevented from exercising my right during such an important procedure,” she said.

Her elderly mother in Samos had struggled even to understand the referendum question, which asks Greeks to vote on the complex credit proposals put forward by the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank (ECB).

Ms Christodoulou said she had likened her country’s dilemma to a struggle with an attacker: you either surrender and hope to escape alive, or fight and risk death.

Pro-government voices have accused Europe of forcing it towards capital controls, after the ECB refused to extend Greece’s emergency cash lifeline. They say the disturbance to people’s daily lives caused by the forced bank holiday and €60 cap on withdrawals will influence their vote.

Yanis Varoufakis, the Greek Finance Minister, accused creditors of frightening voters into accepting austerity.

“What they’re doing to Greece has a name: terrorism,” Mr Varoufakis said. “If the Yes side wins … then Europe, the place where democracy and rationalism were born, will turn into a dictatorial and irrational place.”

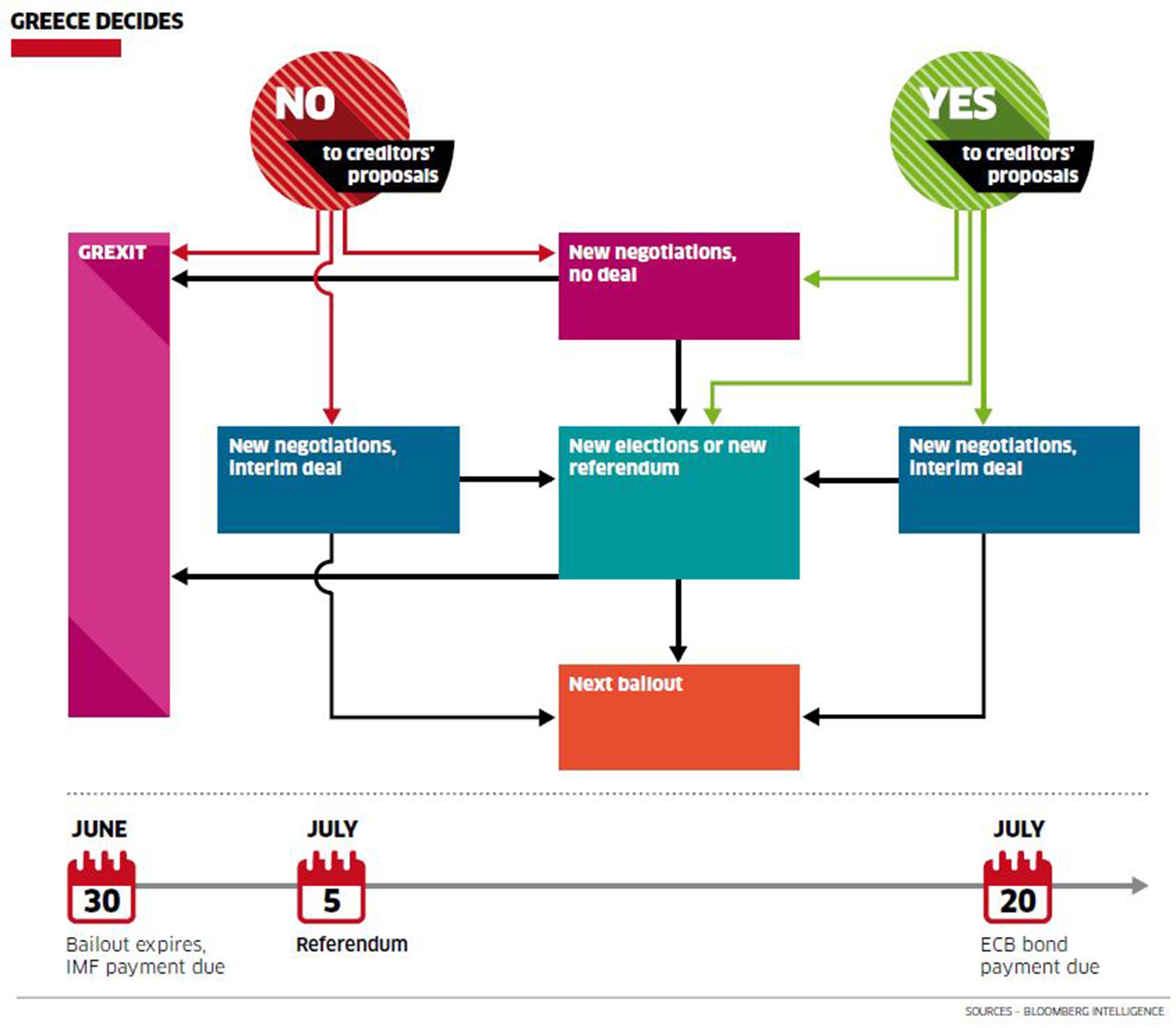

Even if Syriza secures the No vote it has been campaigning for, the next move is far from clear. Fresh negotiations could drag on, putting more pressure on the economy. Syriza is banking on a quick deal in the event of a No vote. Tsipras told the private TV station Antenna last week that he sees a deal with creditors emerging “within 48 hours” of such an outcome.

The mood from some corners of Europe looked to be softening in Greece’s favour. Germany’s Foreign Minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, who is one of Mr Tsipras’ harshest critics, indicated in an article in the German newspaper Bild that a Greek exit from the euro may only be temporary.

“Greece is a member of the eurozone. There’s no doubt about that. Whether with the euro or temporarily without it: only the Greeks can answer this question,” he said.

His comments reflected those from Donald Tusk, head of the European Council, who said on Friday that a No vote would not necessarily result in Greece leaving the eurozone. A No vote would mean “the space for negotiation will be smaller, obviously,” he told the website Politico. “But I would like to warn, for sure, we don’t need any dramatic messages after No voting.”

![Queues form at ATMs. The daily allowance remains set at €60 [£43]](https://static.independent.co.uk/s3fs-public/thumbnails/image/2015/07/04/21/30-Greece-2-AP.jpg)

Meanwhile, Jacques Delors, who was president of the European Commission from 1985 to 1994, called on Greece’s creditors to give the country leeway when he outlined a three-point plan in the French newspaper Le Monde. The plan included reviewing Greece’s debt burden, which the country has called to be lifted.

With a ban on foreign transactions, the economy is all but frozen. Every day, some 50,000 hotel bookings are cancelled, according to the Association of Greek Tourism Enterprises; this is a huge blow as tourism accounts for one in five jobs. Some economists argue that Athens will inevitably have to take far stronger measures than it had originally planned.

“Capital controls are a complete game changer for the Greek economy in a bad way,” said Megan Greene, the chief economist at Manulife and John Hancock Asset Management. “The fiscal gap that Greece will have to close will be much bigger now than it was when they were negotiating, so any deal that Greece is going to get is necessarily going to be a worse deal than the one that is on the table this Sunday.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments