Greece debt crisis: Hollande calls for a 'eurozone government' to further integrate member states – but what will it mean for Britain?

French President wants to recapture former European Commission chief Jacques Delors' vision of the EU as an answer to the muddled response to the Greek debt crisis

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The French President has lobbed a large boulder into negotiations on the future of Europe by calling for a full “eurozone government” with its own ministers, parliament and budget.

Without mentioning Britain by name, François Hollande called for an “avant-garde” to push ahead towards a form of federal government leaving behind countries which opposed further “deepening” or “integration” of the 28-member European Union.

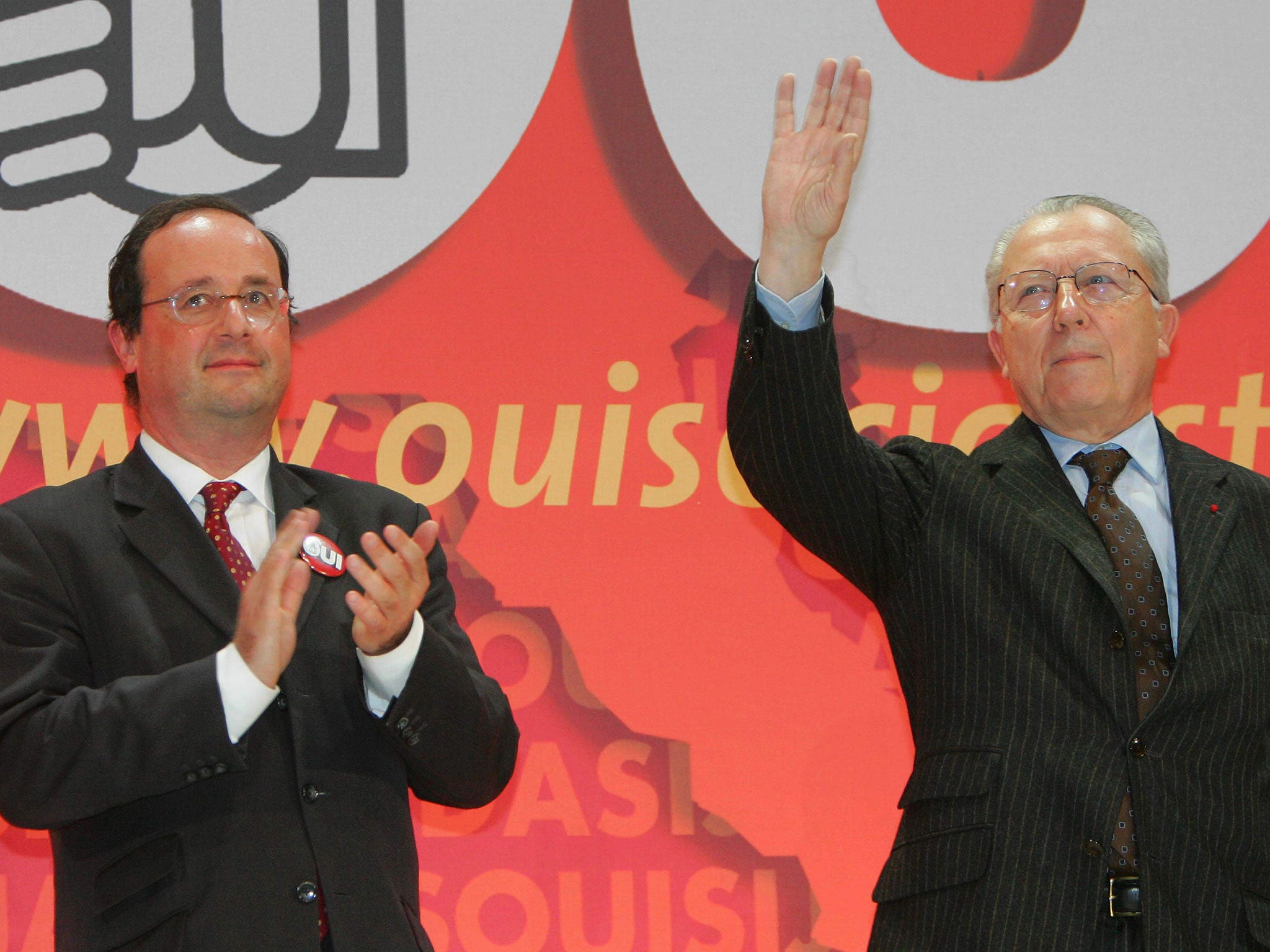

Mr Hollande’s proposals – in an article to mark the 90th birthday of the former European Commission President, Jacques Delors – were framed as a response to the muddled, much criticised and fragile eurozone response to the Greek debt crisis. His comments were, however, also intended to mark out France’s position in negotiations later this year on EU reform, before the in/out referendum in the UK next year or in 2017.

In an apparent swipe at both Germany and Britain, Mr Hollande said that the EU’s problems were caused not by the failure of the European dream, but by a return to national selfishness and a “turning in on oneself”.

“Our biggest threat is not too much Europe, but too little,” Mr Hollande wrote.

As a young and rising politician during the 1980s, Mr Hollande was a protégé of Mr Delors, then the French Finance Minister. In his article in the Journal du Dimanche, Mr Hollande said that it was vital for the EU to recapture the “vision”, the “momentum” and the balance of the original concept for a European single currency put forward by Mr Delors in 1989.

The present structure was too technical and too dryly financial, he said. The eurozone must return to the original Delors concept of a single currency based on “solidarity” as well as “responsibility”.

French politicians, including Mr Hollande, have previously spoken of reviving the idea of a “eurozone government” – a Delors idea vetoed by Germany in the early 1990s. However, the French President’s new comments go even further than the original and controversial Delors plan.

He said that the 19 countries that use the euro should have a “government, a dedicated budget and a parliament to ensure democratic control”.

Although he gave no further details, French government sources said that Mr Hollande was not necessarily suggesting that the EU should have two parliaments – one for the full 28-nation union and one for the 19-country eurozone. His proposed “new” parliament could consist of existing MEPs from euro-using nations, who would meet in separate sessions to cast eurozone votes for eurozone laws.

There would be a eurozone government with its own prime minister, the officials said. This government would have its own budget – separate from the EU budget – to aid and invest in more fragile countries, It would try to harmonise corporation and pay-roll taxes to ensure fair competition in the eurozone.

Such proposals – especially the idea of rich eurozone nation aiding poorer ones – go far beyond what Germany is likely to accept. The tax harmonisation idea will set alarm bells ringing in countries with low business taxes, like Ireland.

The British response is likely to be cautious – but not necessarily completely hostile. By suggesting such a radical redesign of the architecture of the EU, Mr Hollande is also opening the way to some of the reforms, and the treaty changes, that David Cameron is seeking.

Before a dinner with Mr Hollande in May, just after his re-election as Prime Minister, Mr Cameron said that he had “no objection to” and even “supported” the idea of greater economic integration for other EU countries within the eurozone. A “two-speed” Europe might allow Britain to have a looser or semi-detached relationship with the EU, which Mr Cameron could present as a victory.

Many problems remain, however. The French and others insist that, even as part of a “lower-speed” Europe, Britain must remain subject to supra-national European law. The French, the Poles and others will resist further specific exemptions for Britain from EU policies and treaty provisions, such as free movement for European citizens. Mr Cameron and his advisers may also fear that the Hollande plan could undermine Britain’s place in the European single market and leave Britain as a “second-division” European nation in the eyes of the rest of the world.

The new architecture proposed by Mr Hollande is unlikely to be agreed in full in the near future, if ever. It is, in part, a statement of intent that France will resist any attempt by Britain – and de facto by an increasingly assertive Germany – to impose a less ambitious and less “solidaire” form of the EU.

Mr Hollande stood up to the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, for the first time during last week’s emergency summit on the Greek crisis. Although the punitive outcome for Greece was largely shaped by German demands, Mr Hollande steered Ms Merkel away from “Grexit”, the expulsion of Greece from the euro, demanded by German hardliners.

His summit performance was hailed in Italy and Spain as a welcome return of French influence in Europe, after years of Nicolas Sarkozy and Mr Hollande playing second fiddle to Ms Merkel. His opinion article seemed intended to assert the French President’s new-found independence.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments