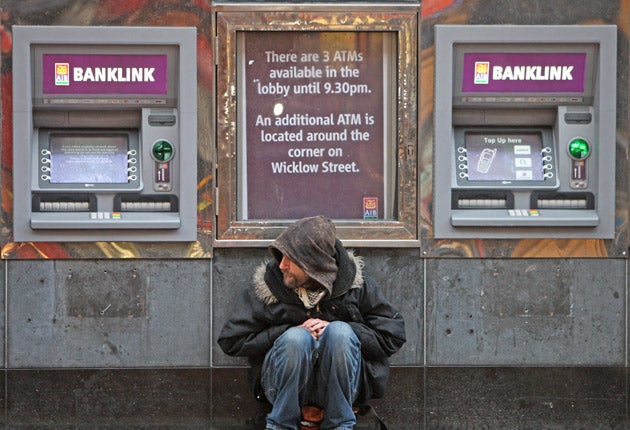

Ghost estates and broken lives: the human cost of the Irish crash

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They stand empty across Ireland: 300,000 unoccupied homes, a silent reproach to those who built them believing that the country's economic boom would never end. As Europe's finance ministers laboured in vain to reach an agreement on how to ease Ireland's economic misery last night, the so-called ghost estates were an awful reminder that the "survival crisis" the politicians were warning was under way had already hit ordinary people.

Dave O'Hara was one of those who bought into the "Celtic Tiger" at the beginning of the decade, eschewing a seven-generation family tradition of carving headstones in favour of a piece of the country's building boom. He founded a firm that constructed bespoke windows and doors for the thousands of upscale homes being built. The firm grew into a multimillion-euro enterprise, until the recession – and the collapse of the building industry – hit in September 2008.

Now his company is in liquidation, and Mr O'Hara, 41, who has one child, is on the dole. He owes the Bank of Scotland more than ¤1m (£850,000).

Like many others, Mr O'Hara's anger is aimed at the banks, which have already been bailed out and seem destined to force the government to seek further help of some kind from Ireland's European partners. "Everyone is responsible for their own actions, but the burden is being brought to bear on the people on the end of the line. In Ireland right now, it's better to owe ¤50m than ¤50,000. The people who have sinned the most are suffering the least," he said, sitting in his cottage along the borderlands between Leitrim and Sligo, in the boggy north-west of the country. "I don't know what's coming, but I know what we've got isn't going to stay. I've lost all faith and confidence in our system."

Not far from Mr O'Hara's home, the "ghost estates" are well-known eyesores along the rugged landscape. And the crisis that created them has hit not just the people who built them, but those who might once have expected to move in, as well. Hundreds of thousands of homeowners have already found themselves saddled with negative equity as a result of the crash, economists estimate, with as many as one in seven families affected.

The toxic combination of the glut of house-building during Ireland's boom and the current dearth in demand means they have been lumbered with a property worth less than the loan they secured to buy it.

Personal indebtedness is also an issue, as are redundancy and the end of easy loans, meaning around 100,000 households are struggling to make regular repayments on the money they owe. And yet, house prices continue to fall precipitously. Together with slumping disposable incomes due to frozen wages and stubbornly high unemployment, still running at more than one in every eight adults of working age, many fear a social disaster is unfolding.

Even for the few who have yet to feel the pinch from the crisis, its effects on families will be felt next week, when the Budget that was brought forward yesterday yanks a further ¤15bn out of the economy through major spending cuts and tax rises.

Many have taken drastic action already. With youth unemployment topping 30 per cent, some have already fled abroad to seek their fortune, or at least stay above the breadline.

The Economic and Social Research Institute think-tank estimates that the labour market will not pick up within the next two years, pushing as many as 100,000 people to seek work abroad. In a country of just 4.5 million, that would cause a dent in potential consumer spending, as well as a level of emigration-fuelled social upheaval reminiscent of the 1980s and after the Second World War. In Dublin, ministers were maintaining a tough-talking stance, refusing to go cap-in-hand to the EU even as discussions were continuing in Brussels. There was a not-so-subtle resentment in the capital that a growing number of European players were insisting a bailout was the best option. Yesterday, Jean-Claude Juncker, the Luxembourg politician leading the group of euro-area finance ministers, said help was there if it was wanted.

There must be a bitter irony in it all for Mr O'Hara. While the Irish government is working hard to avoid calling on the ample help on offer, he continues to struggle. However, he is opposed to Ireland opting for an embarrassing bailout.

"I use be to be pro-European," he said. "But my feeling now is that the solution can't come from Europe. It's akin to giving a credit card to a family already massively in debt. I think the banks need to collapse."

There are some who now want their leaders to swallow their pride and take the help on offer, however humiliating. "Maybe a bailout isn't such an bad thing," said Jackie McKenna, a sculptor in Manorhamilton, Co Leitrim. "It wouldn't be the end of the world. If we don't we won't get out of this. Something needs to be done. Businesses are closing and we need to do something."

Despite his plight, Mr O'Hara remains remarkably upbeat. "I'm actually excited for the future," he said, adding that his situation was a "time for reinvention". Now it can no longer rely on its building sector, the Irish economy will also have to undergo a similar, and painful, transformation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments