Germany shocked by the other lives of civil servants

Twenty years after Berlin Wall fell, more than 17,000 former Stasi members are still working for the state

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Berliners and the citizens of eastern Germany are struggling to digest the news that thousands of former members of the dreaded Stasi secret police were working as their local civil servants, police officers and teachers, almost 20 years after the Iron Curtain collapsed.

More than 17,000 staff currently employed by Berlin and eastern Germany's five federal states were estimated to have worked for the all-pervasive communist police organisation, according to evidence compiled by historians at Berlin's Free University.

Shocking cases came to light after the fall of the Berlin Wall, including a husband who spied on his dissident wife for years and a mother who informed the Stasi about her son after he reached puberty because she considered him a threat to the state.

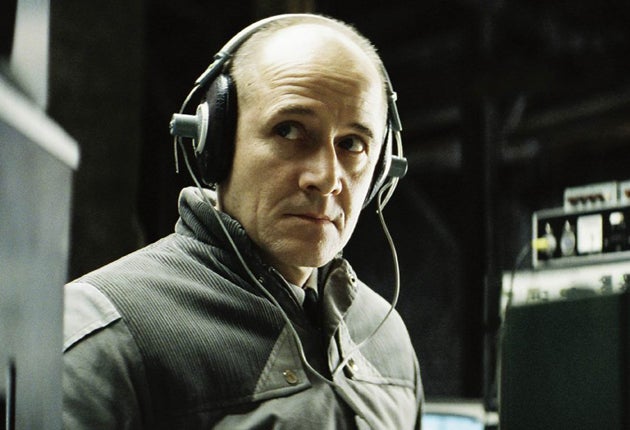

The lengths to which the so-called "Sword and Shield" of the Communist Party went to obtain information was graphically portrayed in the award-winning 2006 German film, The Lives of Others. It tells the story of a ferret-like Stasi major called Gerd Wiessler who is sent to spy on a dissident East Berlin author and his lover by recording their phone calls.

In the film, Wiessler is depicted as a near down-and-out after the fall of the Berlin Wall, forced to paste up street advertisements to earn a living. Yet the researchers say reality was different for thousands of ex-Stasi workers after reunification. Many were able to get around laws adopted by reunified Germany in 1991, and hang on to their jobs because vetting was interpreted differently from state to state.

Klaus Schröder, the head of the research team, said their findings exposed the extent to which regional administrations appeared to have kept their employment of former Stasi agents a secret. "This has achieved a dimension no one expected," he said.

Groups representing the victims of the Stasi's blanket surveillance of the former East Germany's 17 million inhabitants said they were appalled by the disclosures. Ronald Lässig, of the Victims of Stalinism Association, described them as a "slap in the face for every Stasi victim" and demanded that efforts to properly vet civil servants be redoubled.

The Stasi was one of the biggest employers in the former East Germany. It had some 200,000 people working for the organisation full- and part-time and it is estimated that one in every 50 East Germans had Stasi connections. About half of the Stasi's employees were civilians who worked as informants. But the information they gleaned from spying on neighbours, friends and colleagues was used to imprison people, strip them of privileges and ruin careers.

Evidence found by both the Berlin researchers and the authors of a new book on the Stasi, They are Still Among Us, showed that authorities in the eastern state of Saxony allowed half of the former Stasi informers to keep their jobs.

Saxony's police force was said to have been infiltrated by "companies" of former Stasi informants. The state's conservative administration merely ruled that those officers should be given backroom jobs and kept from direct contact with the public. The state is still thought to employ the largest number of former Stasi agents. Last Wednesday, Germany's Federal Criminal Police admitted that 23 former Stasi employees, who were given jobs after reunification, were still working there.

The Stasi disclosures have prompted a political row. Wolfgang Bosbach, the deputy parliamentary leader of Angela Merkel's conservatives, demanded that all civil servants in the east should be re-vetted. But Stephan Hilsberg, a Social Democrat MP, said the mere fact that former Stasi employees were now working as civil servants was not the real issue. "The problem is where they end up," he said, "It is perfectly all right for them to work as janitors but if they end up in positions of authority, it becomes a problem."

Stasi: East Germany's feared secret police

Stasi was the abbreviation used by East Germany's Ministry for State Security, with its motto "Shield and Sword of the Party", the huge and highly efficient secret police force which had the task of identifying and rooting out "class enemies".

The tens of thousands of full-time agents were augmented by hundreds of thousands of part-time spies, making the German Democratic Republic one of the most closely monitored societies of modern times. Every block of flats had its part-time, live-in spook, and residents and the guests of hotels were filmed through tiny holes drilled in the walls. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Communist regime, the Ministry was dissolved. A long-running controversy over the fate of the Stasi's files was resolved with a decision to allow public access to them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments