France's 'great women' finally celebrated as two heroines of French Resistance admitted to the Pantheon

Until now, the notion that France might one day wish to commemorate its 'great women' in a resting place for national heroes was not considered

On the façade of the Panthéon in Paris, there is a carved inscription which means: “For our great men, from a grateful homeland.”

The notion that France might one day wish to commemorate its “great women” in a resting place for national heroes was not considered.

In 224 years, only one woman, the scientist Marie Curie, has been “admitted” to the Panthéon as a result of her own achievements. But the walls of this almost exclusive club of dead, great males are finally about to crumble.

The official list of “great Frenchwomen” will triple, as two courageous and extraordinary women will be added to the list of 71 people interred or commemorated in the domed monument which dominates Paris’s Left Bank.

Both of the new arrivals, to be solemnly welcomed by President François Hollande, were heroines of the French resistance to Nazi occupation from 1940-44.

Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, the niece of General Charles de Gaulle, survived the Ravensbrück concentration camp and died in 2002, aged 82. Germaine Tillion, leader of a resistance group in Paris, was sent to Ravensbrück after being betrayed to the Germans by a priest. She wrote an operetta in the camp and died in 2008, aged 100.

By the choice of their families, neither of the women will be disinterred and re-buried in the Panthéon, but they will be given commemorative plaques.

The only female occupants will remain the cancer and radiation pioneer Marie Curie (1867-1934), reburied in the Panthéon with her husband Pierre in 1995, and Sophie Berthelot, a relatively unknown scientist who was buried in the Panthéon to be alongside her better-known husband, Marcellin Berthelot, in 1907.

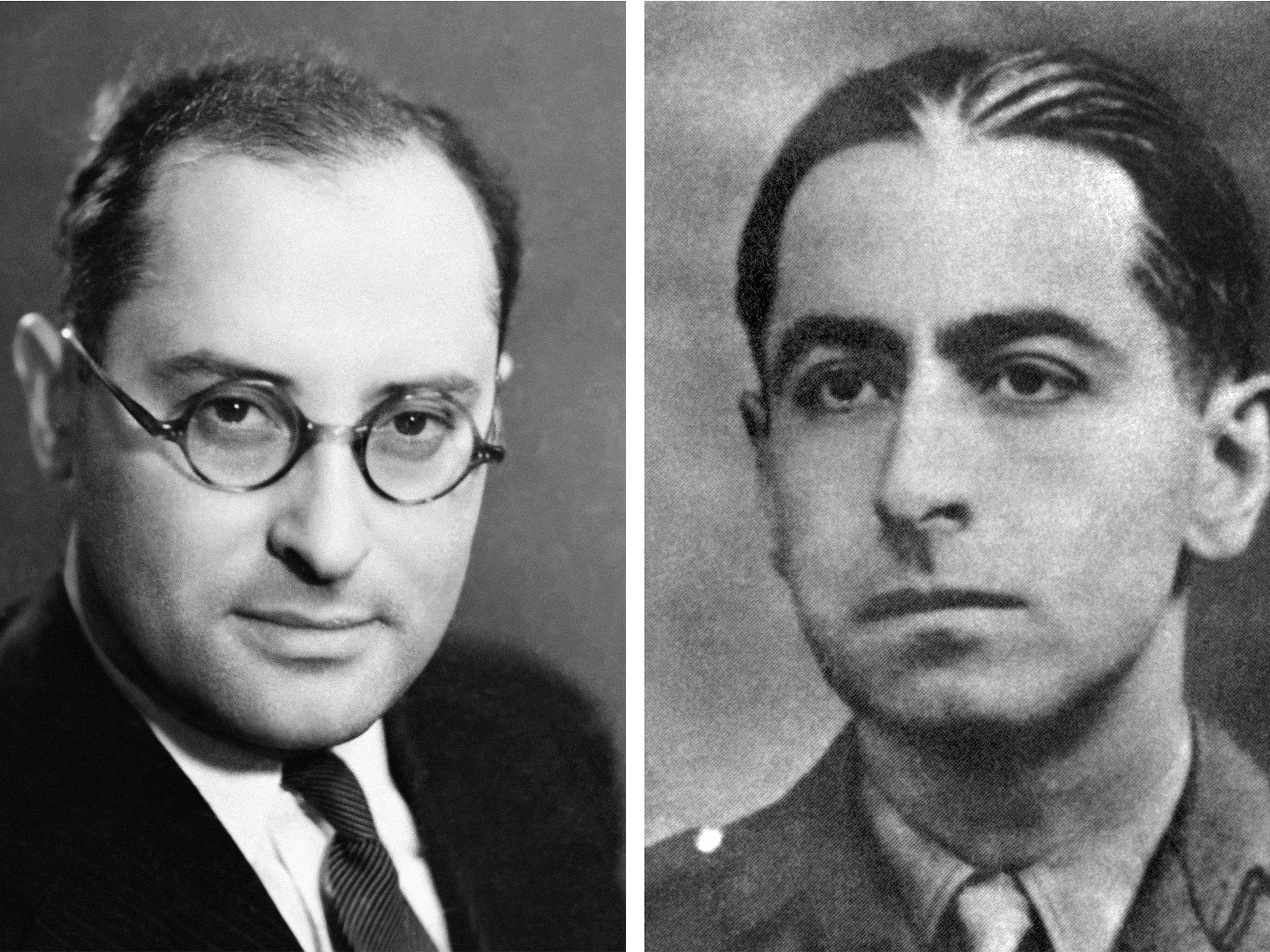

Two other resistance heroes, both killed during the war, will also be admitted to the Panthéon. They are Pierre Brossolette, a journalist who committed suicide, aged 41, under torture in 1944, and Jean Zay, 40, a Jewish former education minister who was murdered by pro-Nazi French militiamen, also in 1944.

Mr Zay is credited with inventing the Cannes film festival. His inclusion has provoked the wrath of extreme right-wing groups who claim that he was “anti-French”.

President Hollande, who selected the names, will make a speech explaining his choices. He is expected to say that the recognition of two extra “national heroines” was long overdue.

He will also praise the two women for their work after the war. Ms De Gaulle-Anthonioz campaigned for the poor in France and the developing world. Ms Tillion was an ethnologist and expert on North Africa, who campaigned for equality and respect for all cultures.

Ms De Gaulle-Anthonioz will be the first “De Gaulle” to be commemorated in the Panthéon. Her celebrated uncle, the leader of Free France from London from June 1940, and president from 1963-9, forbade posthumous honours of any kind in his will in 1970.

Ms De Gaulle-Anthonioz survived her 14 months in Ravensbrück partly because of her name. The Nazi leader Heinrich Himmler decided to keep her alive as a possible exchange prisoner.

Her daughter, Isabelle Anthonioz-Gaggini, said her mother and Germaine Tillion had remained friends after the war: “They wanted people to understand that similar horrors could happen again.”

The Panthéon, originally a church, was commandeered as a secular monument after the French Revolution. Fifty men were buried there between 1791 and the fall of the Emperor Napoleon in 1815.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments