Forgotten: The most radioactive town in Europe

Palomares, Spain, still awaits clean-up 45 years after nuclear accident

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At about 10.30am on 17 January 1966, when Jesus Caceido heard a deafening explosion coming from the village of Palomares, the future mayor of the area had no idea he had just witnessed one of the Cold War's most serious nuclear accidents – or that nearly half a century later, the 1,500 villagers would still be battling to have the ensuing contamination removed for good. After all, they live in Europe's most radioactive village.

Today, 45 years after four nuclear bombs fell near the village when a US Air Force B-52 bomber and a refuelling aircraft collided in mid-air, tens of thousands of cubic metres of contaminated soil and an estimated – although never officially confirmed – half a kilogram of plutonium remain. And the radiation is getting potentially more dangerous, not less.

"As this type of plutonium decays, it is converted into another radioactive substance, americium, which is highly carcinogenic and can be released into the atmosphere," says Igor Parra, a specialist for the Ecologistas en Accion pressure group for Palomares.

"The current risk of contamination is limited. But unless a permanent clean-up is sorted out soon, a small problem will keep on getting bigger. and given that this type of plutonium has a half-life of 27,000 years, there's a lot of time for it to do so."

Mr Caceido – now mayor of the closest town, Cuevas del Almanzora near Almeria in southern Spain, which oversees affairs in Palomares – told The Independent on Sunday on the morning of the anniversary: "We are officially fed up with this. Under normal circumstances, whoever's made this mess should clean it up. Or are we going to be sitting here for ever not knowing what effect the plutonium could have the next day?"

While Mr Caceido and the rest of the villagers are worried about the future, the past is almost equally troubling, given that they have never been publicly informed what consequences the plutonium could already have had in the past half-century. For decades after the accident, agriculture and building continued unrestricted across the entire municipality, and the first full-scale official investigation of the accident was not completed until 2008. Only then were three main contaminated areas totalling some 50,000sq m so much as fenced off, in places only partly. According to Mr Parra, one zone of 21,000sq m has nothing more than a reinforced steel rope to protect it from intruders, mostly hunters taking pot shots at rabbits.

Whether the people of Palomares hunt or not, lasting radioactive damage is still impossible to evaluate. Newspaper reports claim that of nearly 5,000 tests on villagers, 118 were positive for radiation, and only five had a repeat problem. But the figure is impossible to confirm. "Frankly, I don't believe it." Mr Parra says. "There is still no official public report about the Palomares accident, just dribs and drabs of information intentionally leaked to one newspaper. The whole question has been enshrouded in secrecy and neglect."

The past few days have finally seen some progress. Spain's Foreign Minister, Trinidad Jimenez, said the Americans have promised to help in a permanent clean-up. Mr Caceido had a meeting with the US ambassador on Friday, too, in which it was said that a US research team would visit the area shortly. But, given the half-century of waiting for this flurry of developments, activists are determined that Palomares should be kept in the public eye – not the easiest of tasks. Mr Parra says: "Until recently Spanish governments have given the impression that Palomares doesn't matter to them. During George W Bush's presidency alone, the US sent over four delegations. But the Spanish government failed to respond at the same kind of level."

The US's "pragmatism" became clear in 2009, when an agreement that the Americans would provide ¤300,000 a year for villagers' checkups for radiation reached its time limit. Spain did not ask for it to be renewed and the agreement was dropped. And despite the recent declarations of good intentions, described by Mr Parra as "friendly, but with no practical effects", the thorny issue of what to do with the contaminated soil – which, when sifted, would total about 6,000 cubic metres, roughly the size of a large container ship – remains. Spain has nowhere to store the soil and is apparently now insisting that the US take it out of the country. But the US has not yet confirmed if it will accept it, or yet explained why – according to Mr Caceido – after the full investigation carried out by Spanish scientists from the official government body Ciemat, it now wants another, further delaying any possible action.

Whatever happens, the question as to why it is has taken 45 years to reach a possible permanent clean-up for Palomares remains unanswered. Nor will grass-roots anger at decades of neglect by the politicians in Madrid disappear overnight. "We've been abandoned and forgotten, right up to today," Palomares's mayor, Juan Jose Lopez, said on the 45th anniversary of the bombings, "and we're really pissed off about that. Back in 1966 the people of Palomares were living perfectly peacefully here. They hadn't even heard of the Cold War."

In 1966, local ignorance in a tiny, isolated agricultural community in south-eastern Spain about international events meant that when potentially appalling risks were taken – such as the villagers not being evacuated – nobody made a fuss. Then while one Civil Guard posted to watch over a bomb spent a chilly winter night wrapped in the parachute that had guided it to earth, other bits of nuclear projectile were even kept by locals as souvenirs. "I had a lump of one as a paperweight for months until some American soldier took it away," said Manuel Gonzalez, 80, who also reportedly put a screw back in one of the bombs.

Other villagers cleaned up from the clean-up in other ways. When the US investigators failed to find the one bomb that had fallen into the sea despite using five mini-submarines for 81 days, a local fisherman, after being paid a small fortune to act as a guide, told them exactly where it had hit the water. In a surreal Spanish equivalent to "Jones the Post" in rural Wales, the wealthy fisherman was promptly nicknamed "Paco the Bomb".

But despite the Americans shifting 1,300 cubic metres of contaminated soil in the immediate aftermath and one or two locals getting enriched from the accident's fallout, long-lasting environmental damage far outweighed any short-term financial gain. "Palomares is western Europe's most contaminated area for americium and plutonium," Mr Parra claims. "And at the time, Spain and the US connived to keep worries about the incident to a minimum."

In their initial attempt to gloss over what had happened, while the military scoured Palomares for bits of bomb, tourism minister Manuel Fraga and US ambassador Angier Biddle Duke wowed the world media by bathing off a nearby beach. (Now a senator for the Popular Party, Mr Fraga has told colleagues he still has the green bathing suit he used.)

Fast-forward 45 years from Mr Fraga's PR drive, and as former nuclear bombsites go, the vacant lot in the middle of Palomares where one projectile fell certainly looks inoffensive. Hens scratch untroubled in nearby yards, and the grass is so verdant and litter free inside the fencing that if you added a duck pond and took away the signs saying "under radiological vigilance", it could pass for an English village green.

But Francisco Castejon, a nuclear physicist from Ciemat, recently told El Pais newspaper: "We're in a race against time and the longer it goes on, the more dangerous it will be to walk through the village."

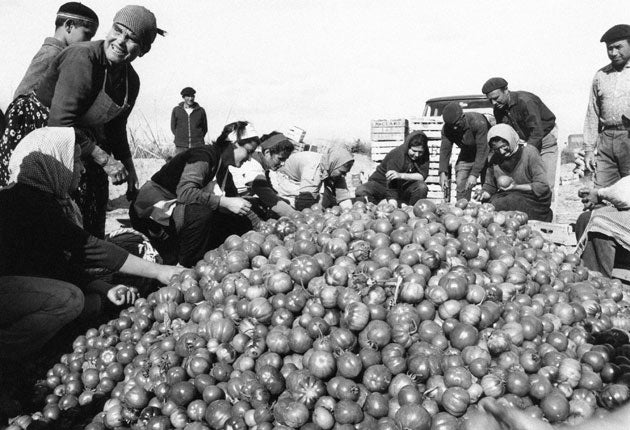

The locals themselves are simply sick of the whole issue: angered that their agricultural produce, like Palomares's fine-tasting raf tomatoes, has to be sold under false labels, annoyed that a natural tourist trap has become a byword for nuclear incidents, and, above all, worried that a clean-up programme costing at most ¤30m has not yet gone ahead.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments