'Don Quixote' author Miguel de Cervantes' coffin found after nine-month search

Author's remains had been lost for 400 years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A nine-month search in a tiny chapel in Madrid for the long-lost remains of legendary Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes has taken a dramatic step forward with the discovery of what is believed to be the coffin of the Don Quixote author.

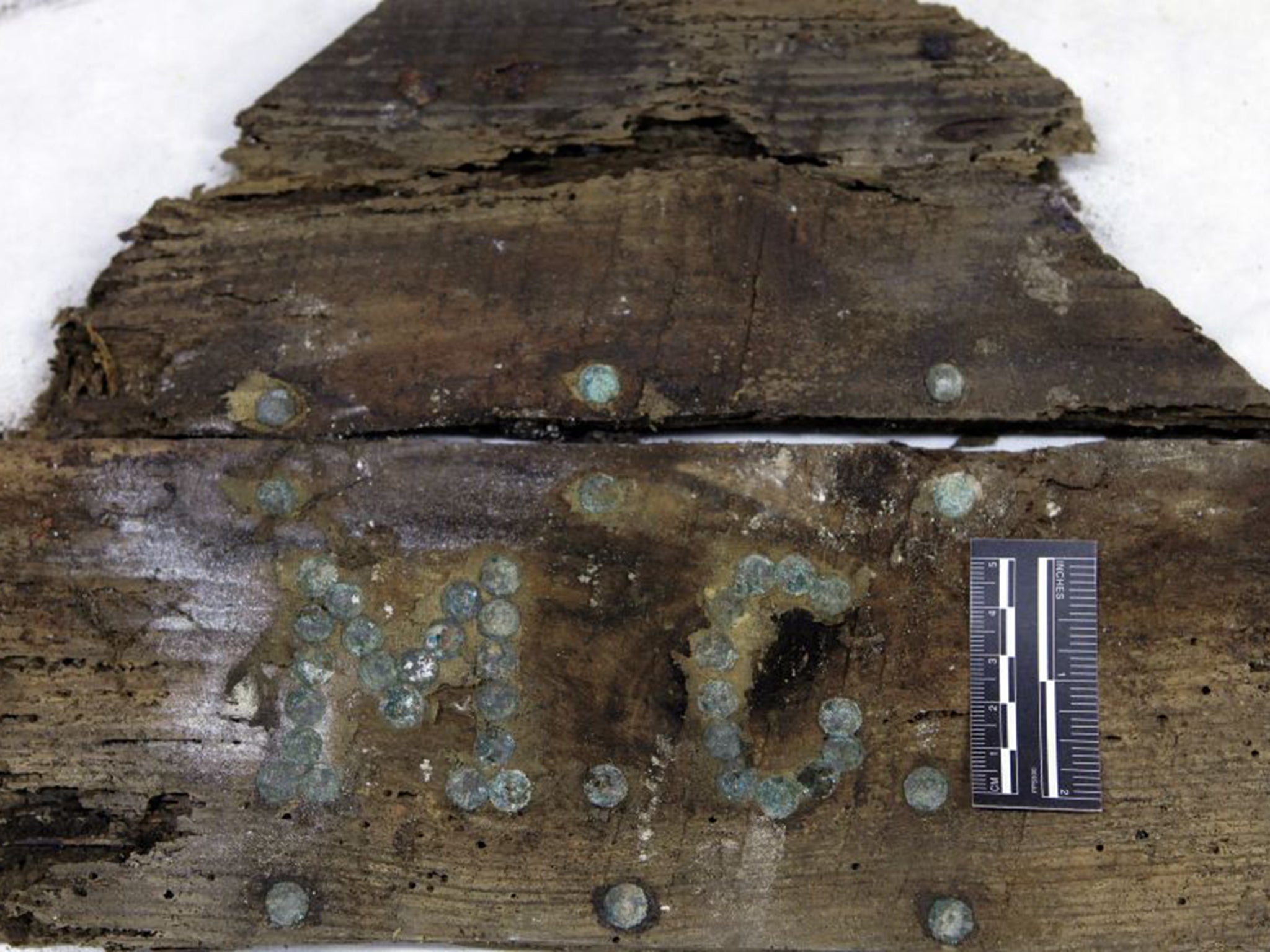

Forensic experts reported that they had discovered two series of tacks forming the thumb-sized initials “MC” on a coffin in the crypt believed to contain Cervantes’ remains. The bones inside the coffin, which are apparently mixed up with those of other burials, are now being analysed to see if they belong to the writer.

Although Cervantes is Spain’s best-known writer, and said to be the first novelist, the exact whereabouts of his earthly remains has been a mystery for centuries.

The penniless author was buried in April 1616 in the Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians, a nunnery in Madrid’s historic Barrio de las Letras quarter. But after the building was reconstructed in 1673, the precise location of the grave was lost.

Identification of Cervantes’ bones could be fairly straightforward. Aged around 70 at death, Cervantes was known to have a deformed left hand, sagging shoulder blades because of arthritis and signs of severe chest bruising due to injuries incurred from an arquebus shot in the naval Battle of Lepanto off western Greece in 1571. Any dentures discovered – or lack of them, given he only had six teeth when he died – could also provide clues.

Should he be discovered, the bones could allow forensic scientists to reconstruct the face of a man currently only known from a picture painted by artist Juan de Jauregui two decades after his death. Believed to have died in poverty, the remains could also reveal whether Cervantes, reputed to be a heavy drinker, died – as has been reported – from cirrhosis.

The reason behind Cervantes’ decision to request burial in the convent both for himself and his wife is better known. After he was captured by Turkish pirates and held in captivity for four years in Algeria, the nunnery provided the ransom, 500 gold pieces, needed for his safe return.

Some 20 forensic scientists began the latest series of excavations last April, locating five different possible locations for graves using a geo-radar system inside the convent’s walls. The aim was to complete the investigation by early 2016, when there will be joint celebrations to mark the anniversary of the deaths of both Cervantes and Shakespeare – who died 10 days before the Spanish author.

But an early, possibly definitive, breakthrough came on Saturday, when they discovered the coffin underneath the convent’s floor, previously covered in bookcases and crates left behind by the publishing company which had rented the building.

Cervantes is a towering figure in Spanish culture. His novel The Adventures of the Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha changed Spanish literature.

The reported €50,000 budget for the search for Cervantes’ final burial place contrasts sharply with the marked lack of financial backing provided by the Spanish government in recent years for exhuming and identifying the tens of thousands of unidentified victims in mass burials from the Civil War.

Some 130,000 victims of General Franco’s death squads during and after the 1936-39 Civil War remain in unmarked graves across Spain. A few regional authorities, such as Andalusia, have provided financial backing for investigations, but since 2011, when the Partido Popular won the general elections, national funding for such projects has dried up.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments