Calais refugee crisis: How the authorities failed the children of the Jungle and how volunteers were forced to do their work for them

Lack of preparation by the authorities has left the young and most vulnerable in terrible circumstances

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When large numbers of children and young people needlessly sleep rough for days in a developed European country such as France, even those most staunchly opposed to the Jungle camp have to take a moment to pause and consider the actions of the governments involved. The words in this article tell a grim story, but make no mistake, it is one. This article isn’t an attack on the authorities; it is an honest account of what has actually been happening in the Jungle over the past few days, what many minors have been subjected to and words from the volunteers overseeing their relative safety.

You would hope that the young and most vulnerable people of the camp sleeping in such a way would be under guard from the police or the gendarmes at this time. According to some accounts, not a single person from the French authorities was dispatched to directly watch over them. The dismantlement of the camp has been talked about for a long time now, and the question is how did such a large undertaking go ahead with such little planning? The volunteers remaining in the camp were left to deal with the children and banded together to stay with them. It turned out only a handful of volunteers, most of them young women, slept rough with them. And sleep they did not. With reports of “fascist vigilantes” circling the camp assaulting people, fires blowing around the camp and plenty of worried children to reassure and organise, they have all been on shifts for days with little to no sleep.

Help Refugees co-founder Josephine Naughton told me: “The authorities demonstrated a clear lack of preparation or contingency plan for the most vulnerable in Calais. We were shocked that though the safety was in their hands, many children were forced to sleep rough. Our volunteers on the ground were forced to provide the care and support that the state failed to deliver. There are more than 1,000 children who still need access to the legal process. We implore both the British and French authorities to fulfil their moral and legal responsibility to these children.”

The registration system for the children was disorganised and chaotic from the start to the present day. Confusion regarding who was meant to register where was not aided by the lack of Arabic translators. Exhausted children were sent back and forth between various checkpoints and queues. I was told they did so bravely and calmly despite the carnage enveloping them.

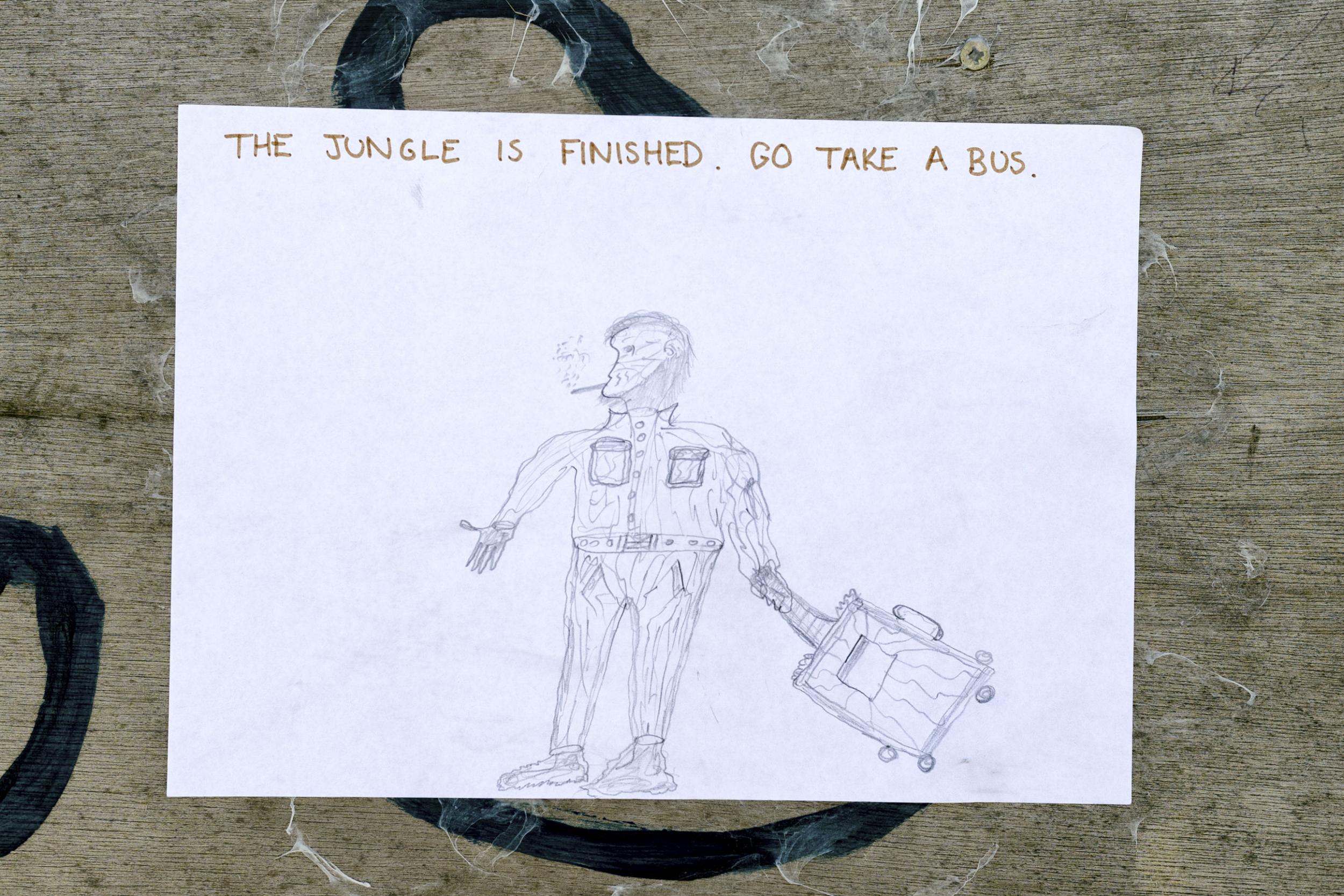

Residents of the camp we spoke to expressed their bewilderment regarding where they were meant to be at any given time, with some thinking the buses for the children were buses to the UK. Volunteers explained to us about the huge amount of pressure this put them under because naturally they were seen as the authoritative figures, and had to actually deal with informing the people with what little they knew.

Information, correct or not, spreads quickly in the camp and many turned up to the wrong queues in the confusion. The majority of the minors were moved to the shipping containers in fairly squalid conditions, but, none the less, much better than the streets or out on the remains of the camp. About 150 were left on the streets or at the mercy of the Jungle, which has been being demolished and burnt down. I was told there was room for the extra minors but the volunteers present were wildly overstretched as it was and could not control the situation.

It has been reported that many children and young people in the camp have gone missing over the past few days. Being surrounded by fire, riot police armed with tear gas and with no access to shelter has terrified many into fleeing.

One of the volunteers, Elizabeth Cragg, told me about an example of these disappearing children: “I was aware of a 17-year-old Afghan boy in the camp whose family have all been killed back home. His only living relatives are his aunt and uncle who live in London. He has been in the camp for three months now and has been waiting for his legal right for asylum to be processed since. He had friends in the same circumstances who have now all left the camp, and just by sheer bad luck he found himself in this position. He stood in the registration line for three days and hadn't got through. I saw him last night, but today he hasn’t been seen by anyone. He’s not here. I think he has given up hope in the legal process and has left.”

Of the volunteers staying with the children during the nights, only one young volunteer called Noha Al-Maghafi could speak Arabic and soon found herself as a kind of information point, on top of the care she was providing. She told us children and youths were coming up to her and asking for information and explanations. Remember these volunteers are young people who are largely not formally trained for processes such as these. It is above and beyond the call of duty and the fact that any responsibility for the well-being and decision-making about the children’s immediate futures has been placed on their shoulders is a regrettable display of the failure of the authorities. One volunteer told me: “We [the volunteers] are doing the work of two governments”. The stress and lack of sleep is visible on their faces, and many have admitted they are close to breaking point mentally and physically.

Last night, when it became clear there were certain children in the camp who had not yet made it onto buses, Al-Maghafi took the responsibility for finding them along with some members of the youth refugee service. The authorities were not helping in this process – in fact, they appear to have been actively hindering it. She told me: “To get there faster I borrowed a bike from one of the minors. Before I could get to the children I was stopped by the police. They told me the bike I was on was stolen and I was put in a cell for the night. I was not well treated and the conditions were horrendous. There was faeces on the walls, it was not heated and I was given a carton of orange juice for the night. They wouldn't let me make a phone call.” She was released on Saturday morning and allowed to return to the camp. Being the only Arabic translator present, her absence will have undoubtedly put a lot of unnecessary strain on the volunteers remaining in the camp.

We witnessed a group of young people and children being taken from the camp where they had been sleeping rough to buses. It began when a man, whose organisation and identity was unclear and unannounced, turned up at the makeshift school in the Jungle where many minors had been sleeping overnight and announced: “If you want to come this way there will be a bus. You are free to come or to stay here. As you wish.” He then drove off and more confusion ensued. A group of around 100 people we were with began asking for a translation and clarification. Once again the responsibility of getting the people to the buses, and informing them was left to volunteers. Three of them, including Noha who was required to translate, gathered the minors around and informed them of the process.

This is what the volunteers who addressed the group of minors told them at this point: “We have been told by the police that there will be buses coming to the bridge. We are not sure where they are going so we cannot give you this information. We must make four groups. One group will be for people who are 14 and under. The second group will be for 15-18. We have been told all will have a chance to be assessed. There will be two groups for any adults. One for adults who want asylum in France, and one for those who don’t. As volunteers some of have worked and lived here for over a year. Today we cannot do anything more than help you organise yourselves peacefully and calmly as you ask for the French state’s help. You need to help the children get separated into those groups and onto the buses. One thing I would advise you as a human, not a lawyer, is that we have been told that people who lie about their age today may have problems later on.”

The volunteers then escorted the group across the south side of the camp to the bus site where they were met by authorities. When the group arrived at the site where buses were indeed waiting, the four groups were assessed and then one by one filed towards the buses through a barricade of gendarmes.

Of all the authorities present, police chief Patrick Visser-Bourdon has been the most pragmatic. On the day he kept his word when he gave it, and was calm in the deplorable situation before him. “He listened to us today, he was not aggressive like some others have been, but despite this, and I hope despite his best intentions, not much has been done up to now.” I can personally attest to the fact that when he was present things seemed to run smoothly, and certainly in front of the press and the chief, the police did their jobs properly and politely. I think he is trying to shift through the chaos to reach a solution and would be dismayed to hear of Noha’s arrest over the ‘stolen’ bike incident.

The process of the all the minors being taken onto the buses was orderly and over within a couple of hours. There are still children left in the camp today, however, and I fear the volunteers of the Jungle will be needed for more nights to come.

View more of Alan Schaller and Emily Garthwaite’s photography here and here.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments