150 years after uniting it, Garibaldi divides Italy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Italy, Metternich said, was "only a geographical expression", but 150 years ago the greatest revolutionary the peninsula ever produced set about proving him wrong.

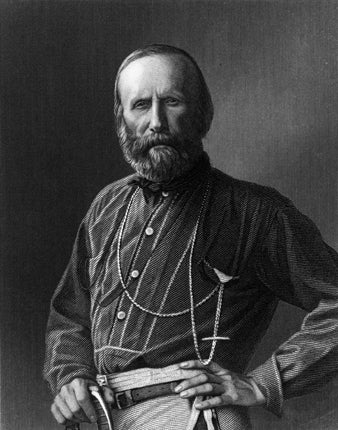

In the most dramatic episode in the long story of Italy's unification, Giuseppe Garibaldi, set sail from Genoa with two small steamers crammed with red-shirted comrades from northern Italy. They were known as the Mille, "the thousand", and they sailed south to conquer Sicily. In less than a month, and against all odds, they had seized Palermo. Soon Garibaldi was master of Sicily and had crossed over to the mainland to continue the rout.

This event has long been regarded as a crucial moment in the creation of the Italian nation, celebrated in romantic paintings and public monuments. The anniversary this week was the starting gun for a whole year of celebrations as Italy looks back on its short but tumultuous history as an independent nation. Organisers promise four major exhibitions and "an extraordinary programme of culture, sport and entertainment". The central exhibition, in Turin, examines Italy's independent history.

The only problem is that, despite the exhortations of the head of state, President Giorgio Napolitano, and lectures from on high by the establishment media, Italians appear conflicted about even marking the anniversary.

The Northern League's founder and leader, Umberto Bossi, called the celebrations "useless things." The party's newspaper demanded rhetorically, "The unity of Italy – what's there to celebrate?" and described the birth of the unitary state as "contrary to nature and history."

Another senior figure, Robert Cota, went so far as to describe Garibaldi as "a criminal who sowed death and destruction".

The League began life as a coven of extremists in the prosperous north, inveighing against "Big Thief Rome" and demanding secession from the supposedly blood-sucking south.

Silvio Berlusconi brought League members into his first government in 1994, and though they pulled the plug on that fragile administration, today they are his strongest coalition allies. They may have backtracked on their secession demands but they never tire of reminding people that the unity of the nation should not be taken for granted while they are around.

President Napolitano was on the defensive when he travelled to Genoa this week to honour the Thousand. "To celebrate the unity of Italy is not a waste of time or money," he declared. He urged Italians to show "a stronger sense of Italy and of being Italian".

And he defended Garibaldi, long regarded as the national hero but recently, as he put it, "incomprehensibly the object of gross denigration by new detractors".

"Let us incite ourselves," he said, "to have a bit more national pride."

The President's problem is that, a century and a half after the founders of the unified state set about, as they put it, "making Italians," the work is still only half done.

In Garibaldi's day, all the peoples of the peninsula spoke the dialect of their own region, so when the red shirts turned up on the shores of Sicily, they were regarded as scarcely less foreign than the British naval sailors who backed them up.

National wars, a national education system and nationwide television helped to forge a national language, but dialects are still alive. Pride in one's home town and its culture and food is still far more commonly encountered than pride in being Italian.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments