The gentleman robber who mourned at his own funeral

Descendant tells what really happened to Australia's Robin Hood

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

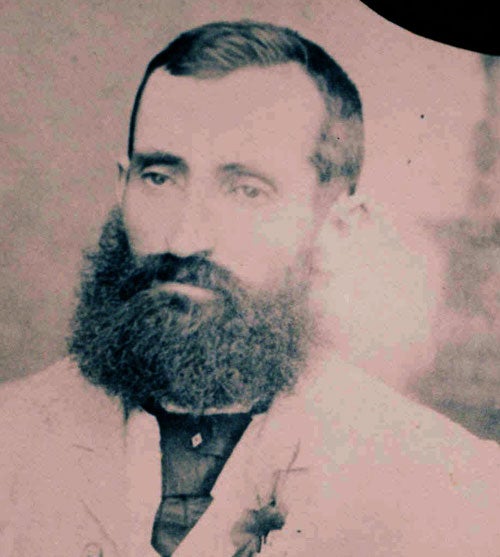

Your support makes all the difference.A Robin-Hood-style figure who helped the poor and oppressed, Frederick Ward was nicknamed the "gentleman bushranger" because he never used violence and was always polite to his victims. In 1870 Ward – or Captain Thunderbolt, as he was also known – was shot dead by police near Uralla, in northern New South Wales. Or was he?

A new book written by one of Thunderbolt's descendants claims that the man buried in the cemetery at Uralla is not Ward, but his uncle, Harry. Ward himself escaped to the Californian goldfields and then settled in Canada, where he lived a quiet life before dying in 1903, his family believe.

Barry Sinclair, whose great-great-grandmother was the bushranger's mother, claims in his book, Thunderbolt: Scourge of the Ranges, that police quickly realised they had killed the wrong man but concealed their mistake – a cover-up that has continued for 140 years.

Thunderbolt roamed northern New South Wales for six years, stealing from properties and holding up mail coaches. Once, he and a partner held up an inn near the town of Gunnedah, then danced and drank until police arrived.

Eventually, so the story goes, he was cornered at a creek outside Uralla by a zealous young constable, Alexander Binney Walker. Mr Sinclair believes that Walker, who was shot at during the pursuit, knew he had the wrong man.

"Fred Ward had never shot at the police at any time in his career, so Walker knew straight away that it was not Thunderbolt," he said. Walker then hid his victim's body, according to Mr Sinclair. When it was found by senior police, they knew immediately that the dead man was not Thunderbolt, but his uncle, another fugitive from justice.

To cover up their mistake, they offered one of Ward's former accomplices, Will Monckton, an early release from jail in exchange for identifying the body as Ward's. The funeral went ahead, and was attended by a tall woman dressed in black, whose face was hidden by a veil, and who walked with a manly gait. Ward's family believe it was the bushranger, come to pay final respects to his uncle before slipping out of the country.

The author said police were under pressure to kill the charismatic Ward because the authorities feared he might inspire a revolution. "It was not long after the Eureka Stockade [a popular uprising on the Victorian goldfields], and there was a lot of civil unrest at that time against the British establishment."

Mr Sinclair said that Thunderbolt, who gave away much of the money he stole, had a lot of local support. "Women would hang out red sheets to let him know the police were around, or white sheets to say, 'You're OK, come in and have a meal.'"

Ward was once imprisoned on Cockatoo Island, in Sydney Harbour, but escaped with the help of his wife, Mary Ann Bugg, who swam out to the island. The couple had four children together, despite being constantly on the run.

The leader of the National Party in New South Wales, Andrew Stoner, called on the state government to release all official paperwork on the case. As the Thunderbolt story was part of Australian folklore, he said, "it's in the best interests of our democracy and good government to break through the wall of silence".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments