Australia offers new home to its would-be migrants… in Cambodia

Canberra’s latest ‘solution’ to its refugee problem has shocked even seasoned observers. Kathy Marks reports on what Amnesty has called ‘a new low’ in the country’s treatment of asylum seekers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a lavishly decorated conference room in the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh, champagne glasses clinked incongruously as the ink dried on Australia’s latest deal to divest itself of asylum-seekers fleeing torture, war and persecution.

Under the secretive agreement, Cambodia will resettle an unspecified number of refugees currently held in an Australian-run detention centre on the Pacific island of Nauru. In exchange, as well as paying resettlement costs, Canberra will donate an extra A$40m (£21.5m) in aid over the next four years.

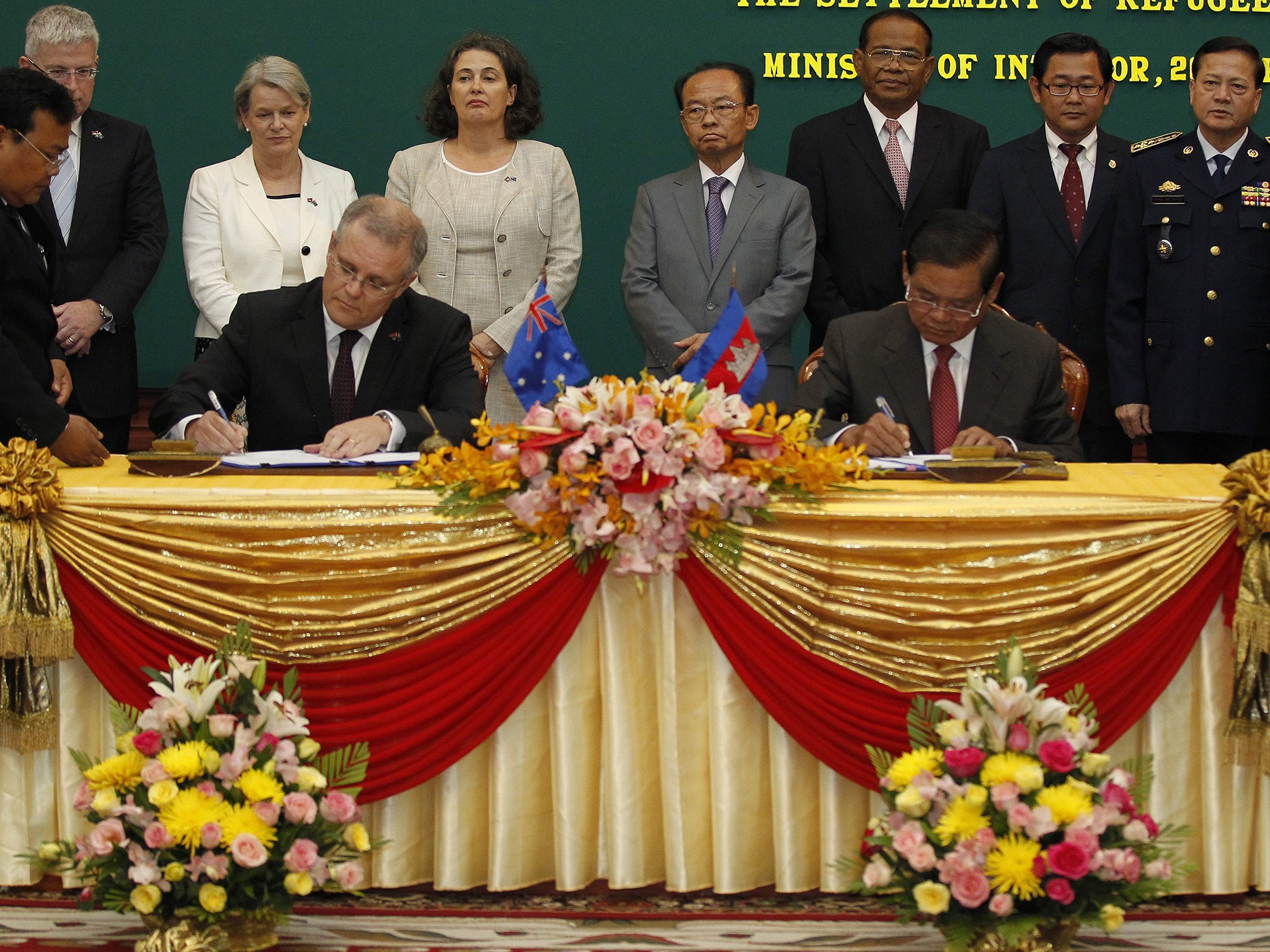

The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed by Australia’s Immigration Minister, Scott Morrison, and Cambodia’s Interior Minister, Sar Kheng, cements Australia’s hardline stance on asylum-seekers who arrive by boat. But even seasoned observers of its policy over the past decade are appalled.

Still recovering from civil war, genocide and Vietnamese occupation, Cambodia is one of the world’s poorest nations. It has a shocking human rights record. It has sent asylum-seekers and refugees back to countries from which they fled. Those who escape that fate live on the margins of Cambodian society.

Amnesty International branded the deal “a new low in Australia’s deplorable and inhumane treatment of asylum-seekers”. The UN High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) called it “a worrying departure from international norms”. Alastair Nicholson, a former chief justice of Australia’s Family Court, said it was “inappropriate, immoral and likely illegal”.

Refugees, mainly from the Middle East, Afghanistan and Sri Lanka, will begin arriving in Cambodia – ruled by Prime Minister Hun Sen for more than three decades – before the end of the year. How they will survive in a country dependent on foreign aid and unable to provide for its own citizens is unclear. The MOU, released last night, is scant on detail.

The signing ceremony itself was bizarre, according to accounts by the Cambodia Daily and other media. After entering the room, at the Interior Ministry, Mr Kheng and Mr Morrison sat down and, without a word, signed the document. The silence was broken only by a waiter tripping and dropping a tray of champagne glasses.

After a brief toast, the pair departed, ignoring questions from journalists herded behind a gold rope. The whole thing was over in less than five minutes. And thus was the fate of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of the world’s neediest people decided.

Australia’s practice of dumping its asylum-seekers on other, often impoverished nations in exchange for hard cash dates back more than 10 years, and has been embraced since then by governments of every complexion.

After the infamous Tampa incident of 2001, when the conservative prime minister John Howard dispatched the SAS to prevent a Norwegian tanker carrying shipwrecked asylum-seekers from docking at Australia’s Indian Ocean territory of Christmas Island, Mr Howard devised the chillingly named “Pacific Solution”.

Those undertaking the hazardous voyage from Indonesia, often in flimsy wooden fishing boats, were intercepted by the Australian Navy and transported to remote and desolate Nauru or to Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island, where they were detained while their asylum claims were processed.

Labor’s Kevin Rudd abolished the reviled policy in 2008. However, in 2012 his successor, Julia Gillard, revived it after her “Malaysia Solution” – which would have seen “boat people” sent to a country notorious for incarcerating refugees – was declared illegal by the High Court. Ms Gillard had also tried, without success, to persuade tiny East Timor to take Australia’s refugees.

Now, courtesy of Tony Abbott’s ultra-conservative government – which was elected on a promise to “stop the boats” – is born the “Cambodia Solution”. Unlike Malaysia, Cambodia has at least signed the UN Refugee Convention. But it “has a terrible record for protecting refugees”, according to Elaine Pearson, Human Rights Watch’s Australia director.

In 2009, for instance, 20 Uighurs – a persecuted Muslim ethnic minority in China – who had sought asylum in Cambodia were deported to China at gunpoint. The UNHCR was in the middle of processing the claims of the group, which included a pregnant woman and two children. As of last December, 17 of the 20 were still in detention in China, according to the World Uyghur Congress, with some sentenced to between 16 years and life in prison following secret trials on unknown charges.

According to Human Rights Watch, Australia is failing to honour its responsibilities under the Refugee Convention, because Cambodia is not a “safe third country”. Highlighting human rights abuses by security forces, it says “those living on the margins – including refugees and asylum seekers lacking employment, Khmer language skills and a social network – are at particular risk”.

The asylum deal was signed amid a crackdown on dissent and anti-government rallies. In January, at least four people died when military police opened fire on striking garment industry workers.

One condition set by Cambodia was that it would only resettle people who came voluntarily. That leaves refugees on Nauru in an invidious position. They either make the dubious move or remain on the tiny island, in conditions deplored by UNHCR, waiting for a better offer or a change of Australian policy. The same offer is expected to be made to refugees on Manus Island.

Mr Morrison declared that Cambodia, “as a party to the Refugee Convention… is demonstrating its ability and willingness to contribute positively to this humanitarian issue”. Refugees, he said, “will have an opportunity of a life here… free of the persecution that made them flee their home countries”.

Yet only last January Australia publicly condemned Cambodia’s human rights record during a UN hearing, castigating it for “the disproportionate violence against protesters, including detention without trial”.

Human rights groups there are also horrified. “Cambodia is poor as hell,” Ou Virak, the chairman of the Cambodian Centre for Human Rights, told Associated Press.

About 100 Cambodians, including Buddhist monks, protested outside the Australian embassy in Phnom Penh today. At least one demonstrator was injured during clashes with riot police. Son Chhay, an opposition politician, said: “We don’t want Cambodia to become a trash bin for unwanted refugees.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments