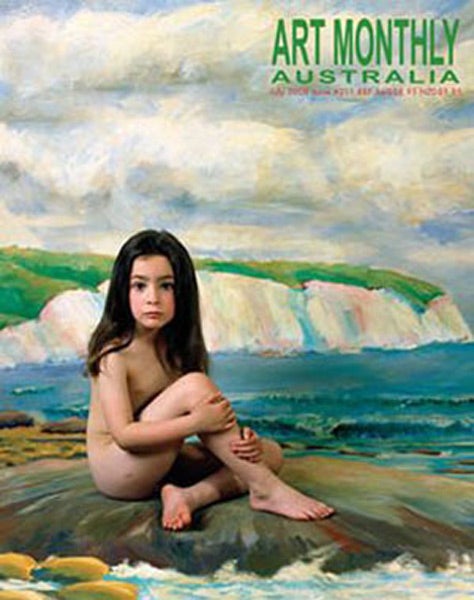

Art or abuse? Fury over image of naked girl

A magazine has reignited debate about the censorship of artworks

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In itself, the picture is simple. It shows a girl of six in a demure pose, sitting on a rock with white cliffs in the background. Its impact comes from the fact she is naked and the photograph is on the cover of Australia's leading arts journal.

According to the editor of Art Monthly, its latest cover is an effort to "restore dignity" to the discourse about the artistic portrayal of children. To its critics, including the Australin Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, it is "disgusting". What it has achieved is to bring to the boil a simmering row over the difference between art and pornography in a country with a long tradition of censorship.

The debate has been close to exploding since police swooped on a Sydney gallery in May and seized photographs of naked adolescent girls taken by the acclaimed artist Bill Henson. Police quietly abandoned their inquiry a couple of weeks later, having found nothing to justify charges against Henson or the gallery, and the pictures were put back on display.

Art Monthly's cover, published this month with two further photographs of the six-year-old inside, was clearly designed to provoke. It has succeeded, bringing calls for the magazine's public funding to be withdrawn and for new protocols on the portrayal of children in art. While supporters of artistic freedom defended Art Monthly's right to publish, child protection campaigners were affronted and Mr Rudd, referring to such images, said: "I can't stand that stuff... We are talking about the innocence of little children here. A little child cannot answer for themselves about whether they wish to be depicted in this way."

But the controversy was complicated by the intervention of two unexpected players. One was Olympia Nelson, the girl in the photo, which was taken five years ago by her mother, Polixeni Papapetrou. The other was Mr Henson – or, at least, "a source close to him".

Olympia, now 11, said: "I was really, really offended by what Kevin Rudd said about this picture. It is one of my favourites – if not my favourite – photo my mum has ever taken of me."

However, Henson's associate said the artist thought the choice of cover image displayed "a lack of judgement only serving to drive deeper divisions in the community". That comment may say more about Henson's fears of being charged and pilloried as a child pornographer than about his genuine views. Nevertheless, it was grist to the mill of Hetty Johnston, a child protection activist, who said: "When [art and pornography] collide, we have to err with the children. We need to put a line in the sand – because clearly some of those in the arts world can't – and say this is a no-go zone."

But just where that line should be drawn is as unclear as ever. Liberals argue that it all hinges on context and intent – if an artist has no intention of titillating, a work is not pornographic. And there is a difference between posting nude pictures of children online and displaying them in a gallery.

But for Ms Johnston and like-minded people, all nude images of children are sexual and should be banned. To them, Olympia's protestations are irrelevant. She could not have consented to being photographed at six and, at 11, is still not mature enough to pronounce on the rights and wrongs.

Once again, the matter looks likely to end up in the hands of police, thanks to the Opposition leader Brendan Nelson, who has asked officers to investigate. He said: "These people with Art Monthly have sought to... send a two-fingered salute to the rest of the country about the controversy surrounding Bill Henson's photography. I think it is time for us to take a stand."

This is, of course, an age-old debate and one not confined to Australia. It has a long history of censorship, and those old enough to remember books banned in the Forties, Fifties and Sixties could be forgiven a shiver of déjà vu. They included James Joyce's Ulysses, James Baldwin's Another Country, Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, Norman Mailer's The Naked And The Dead and, naturally, D H Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover.

The visual arts, too, have come under scrutiny. In 1982, police raided the Sydney gallery of Roslyn Oxley, where Henson's show was to be held, and removed works by a Chilean-born Australian, Juan Davila. His graphic sexual images were said to offend public morals. But the then state premier, Neville Wran, rather more cool-headed than his contemporary counterparts, intervened and the works were reinstated. Police may well scratch their heads about Olympia's photo. Some observers say that only in a climate of moral hysteria could the image be deemed sexually provocative.

Martyn Jolly, head of photography at the Australian National University, defended Art Monthly, saying: "If you are editor of a magazine which is meant to be reporting on Australia on a month-to-month basis, and this has been the biggest thing in Australian art for a long time, you would be [neglecting] your duty if you didn't actually discuss the debate.

"We aren't going to let politicians, who are always wanting to jump on populist bandwagons, dictate what we can and can't show."

The Australia Council, which funds Art Monthly, defended the magazine, saying: "For many years our society has managed to differentiate between artistic creativity and the totally unacceptable sexual exploitation of children."

Artists who shocked with child images

Marcus Harvey

Harvey's portrait of the Moors murderer Myra Hindley, created from a collage of hundreds of copies of children's hand-prints, caused outrage at the Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy in December 1997. Winnie Johnson, the mother of one of her victims, pleaded for the picture to be excluded. Hindley herself sent a letter from jail requesting thather portrait be removed, out of respect for the victims' families. Despite protests, the portrait remained, until protesters daubedit with eggs and ink.

Tierney Gearon

The American photographer became the centre of controversy in 2001 following complaints from the public over an exhibition at the Saatchi gallery in London. Police warned that Gearon's works, which showed her children naked, could be seized under indecency laws. There were calls from the tabloids for the exhibition to be closed. But the artist received the backing of Chris Smith, who was Culture Secretary at the time. Mr Smith condemned the police for censoring artistic freedom.

Betsy Schneider

The American photo-artist's exhibition, Inventories, found itself in a storm after opening at the Spitz Gallery in east London in 2004. The show consisted of pictures of Schneider's daughter naked taken at intervals from infancy to five years old. Hours after the show opened, it was closed amid complaints that it was pornographic. Members of the public had been seen taking their own photographs of the exhibition.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments