Vietnam War 40 years on: Ex-Marines recall being on the final choppers out of Saigon

‘I felt like I was in a war movie, seeing it in 360 degrees’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

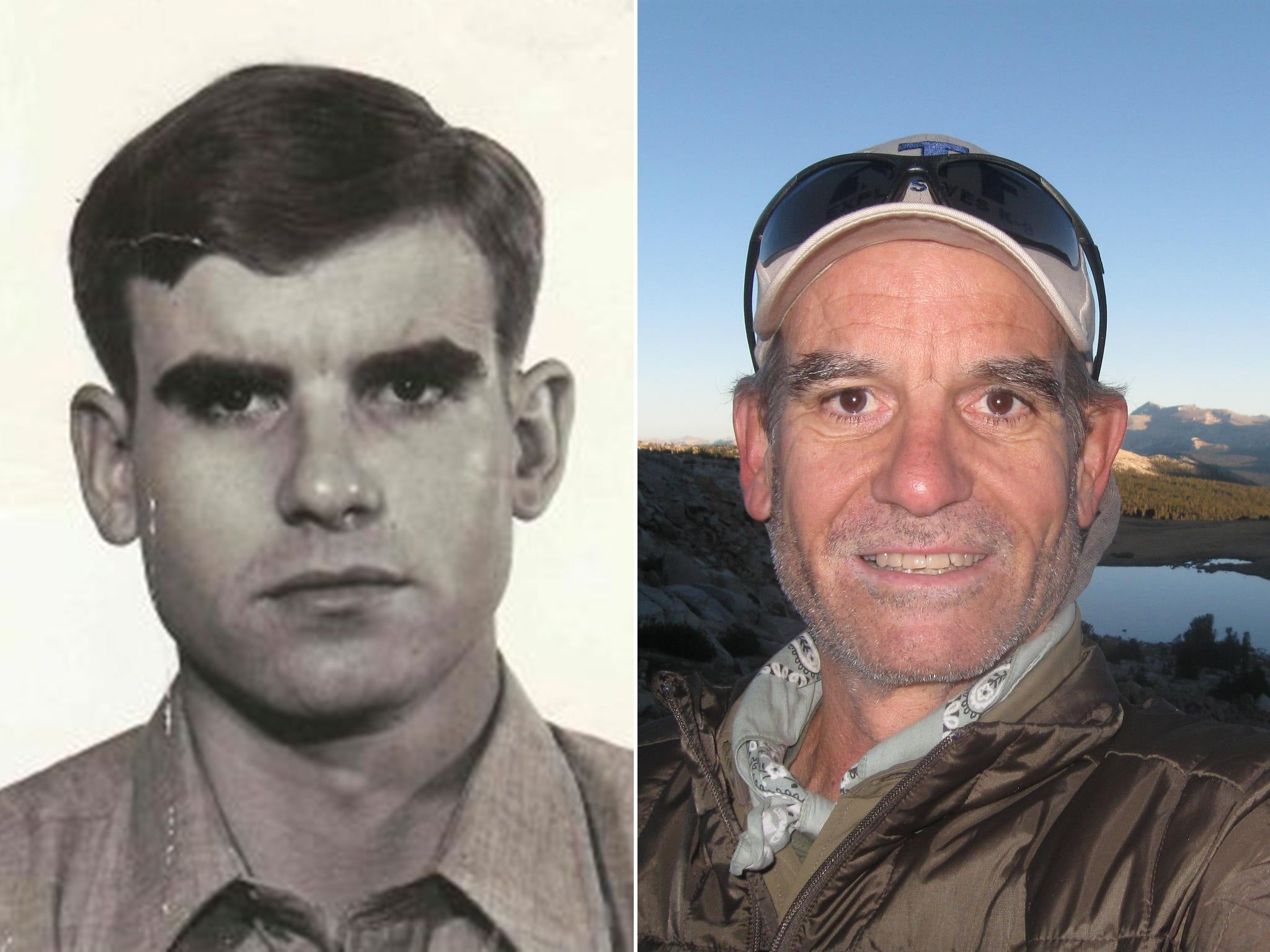

Your support makes all the difference.Rich Paddock was on the roof when he realised the end was near. On the afternoon of 28 April 1975, the young US Marine Sergeant was following orders to burn confidential information atop the US Embassy in Saigon – the highest vantage point in the South Vietnamese capital.

“I heard rumbling in the distance,” said Paddock, who had turned 21 two months previously, and been posted to Saigon six months before that. “At first I thought it was a rainstorm, but when I went up to the helicopter pad I could see aircraft bombing the airport. They finished their bombing runs and flew out over Saigon, which at the time was a no-fly city. The anti-aircraft fire was massive. I felt like I was in a war movie, seeing it in 360 degrees.”

In fact, Paddock had a front row seat for the final days of a real war. On the early morning of 30 April, 40 years ago today, he would be back on the same roof, waiting for a helicopter to carry him and his fellow Marines to safety – the very last US servicemen to leave Vietnamese soil.

The Vietnam War had ostensibly come to an end with the Paris Peace Accords of 1973, but when the hawkish President Nixon was forced from office the following year, the North Vietnamese were emboldened. In Spring 1975 they began seizing control of the South with alarming speed, and by the last week of April they were within sight of Saigon.

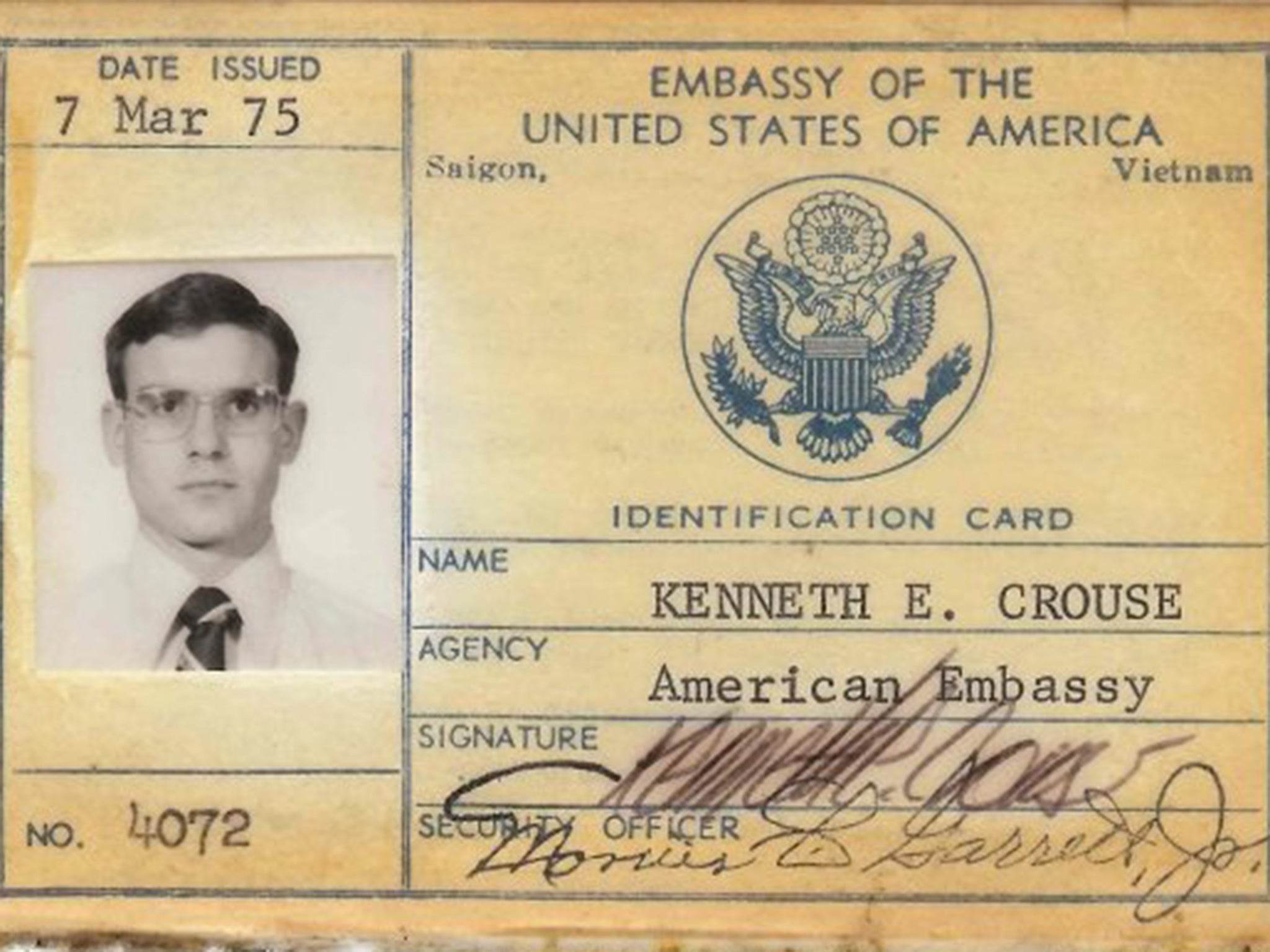

During the days before Paddock witnessed that bombing run, the US evacuated more than 50,000 people by plane: its own citizens, South Vietnamese allies and others. Among the Americans still left in Saigon were the Marines assigned to protect the Embassy and its personnel, including Paddock and Ken Crouse, a 19-year-old Lance Corporal who had been in country for just 60 days.

By 4.30am on 29 April, the Marines had abandoned their barracks and were sleeping on cots and couches inside the main embassy building. Crouse was awake on the roof to watch as the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) bombarded the Tan Son Nhut airfield a few miles away. “I could see the rockets landing on the runway, the ammo and fuel dumps going up in flames,” he said. “I felt a sense of dread that we had Marines out there.”

The rockets had killed Crouse’s friend Darwin Judge, 18, who had graduated from high school the previous summer, and Charles McMahon, 21, who had been in the country for all of 11 days. They would be the last two US servicemen killed in action in Vietnam.

With Saigon surrounded and the airstrip smouldering, the evacuation went on by helicopter. Over the next 19 hours, in an operation known as Frequent Wind, a further 6,000 people would be flown to international waters. US Ambassador Graham Martin, whose own son had been killed in the conflict, departed the Embassy roof early on the morning of 30 April.

As the remaining Vietnamese in the Embassy compound realised they weren’t going to be evacuated, they drove a fire-truck through the locked doors of the building in a bid to reach the roof. The Marines had to fend them off by throwing teargas into a narrow stairwell. “I was just a young Lance Corporal trying to do the best job I could,” Crouse said. “But a lot of the Marines had history in Saigon. They’d established friendships, and for some there was a real sense of abandonment.”

Dawn was breaking as Crouse and Paddock lifted off. US troops had been in Vietnam so long that Paddock’s own father had fought in the war several years beforehand. “From the helicopter I could see a lot of fires,” he said. “I could see the NVA tanks on the edge of the city. Because my father had been there too, the historical significance of the moment sunk in. I recognised that this really was the end of American involvement in that part of South-east Asia.”

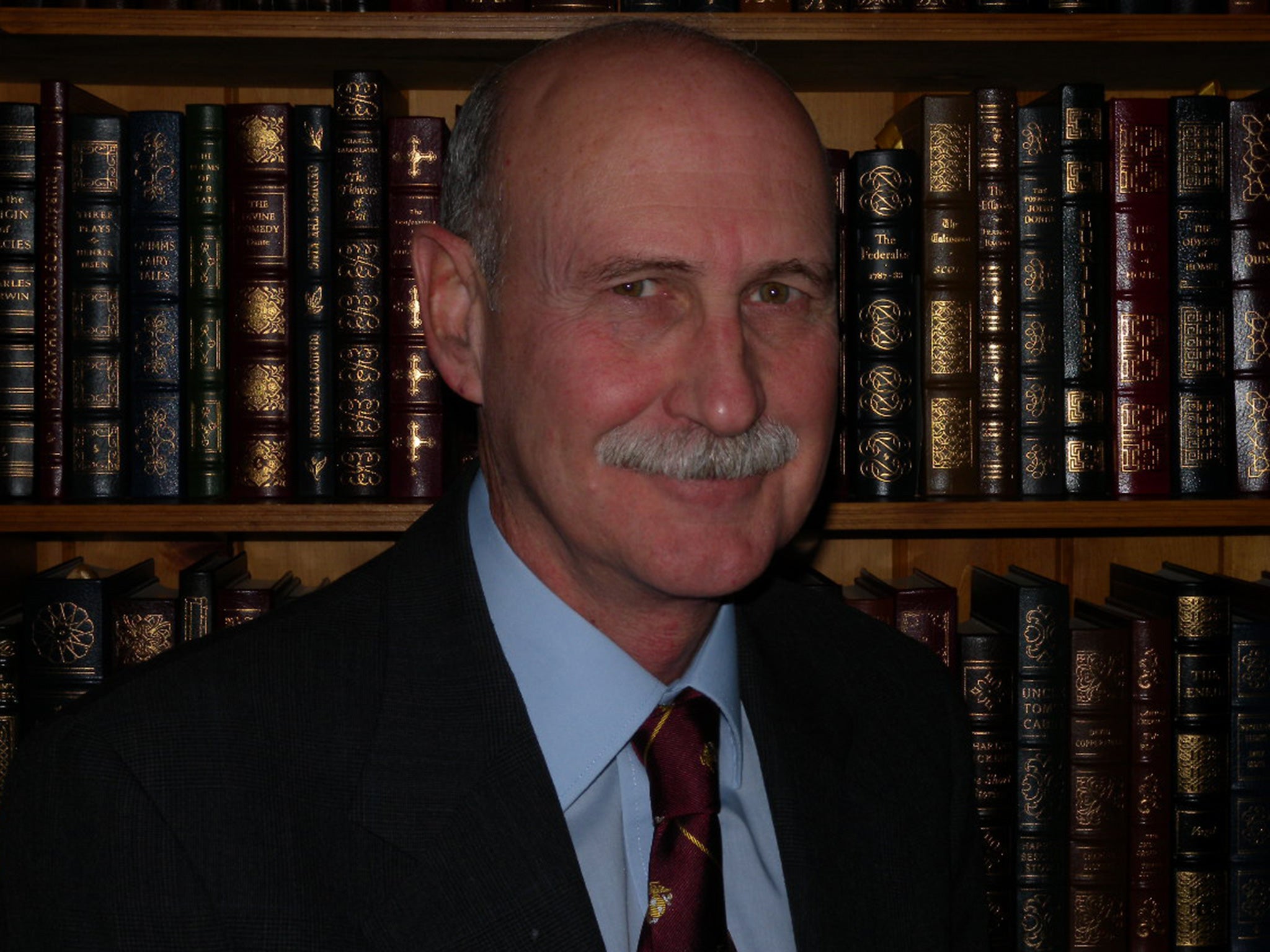

The last 11 Marines left the Embassy roof just before 8am. By the end of the day, the NVA had taken Saigon, and Crouse and Paddock were aboard the USS Blue Ridge, bound for Manila. Reassigned to embassies in Ethiopia and Brazil respectively, both men left the Marine Corps in 1977 and returned home to settle in California.

On Friday, Crouse will mark the 40th anniversary with several of his Saigon colleagues in Washington DC. More than a dozen former Marines will be in Saigon – now known as Ho Chi Minh City – to dedicate a plaque to Judge and McMahon. But Rich Paddock has never returned. “When people ask me why, I say ‘Just visualise a Japanese pilot going to Pearl Harbour and honouring the pilots who were killed bombing those ships,’” he said. “I have no interest in going back to Vietnam.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments