The Big Question: Why is opium production rising in Afghanistan, and can it be stopped?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

Nato and the US are ramping up the war on drugs in Afghanistan. American ground forces are set to help guard poppy eradication teams for the first time later this year, while Nato's defence ministers agreed to let their 50,000-strong force target heroin laboratories and smuggling networks.

Until now, going after drug lords and their labs was down to a small and secretive band of Afghan commandos, known as Taskforce 333, and their mentors from Britain's Special Boat Service. Eradicating poppy fields was the job of specially trained, but poorly resourced, police left to protect themselves from angry farmers. All that is set to change.

How big is the problem?

Afghanistan is by far and away the world's leading producer of opium. Opium is made from poppies, and it is used to make heroin. Heroin from Afghanistan is smuggled through Pakistan, Russia, iran and Turkey until it ends up on Europe's streets.

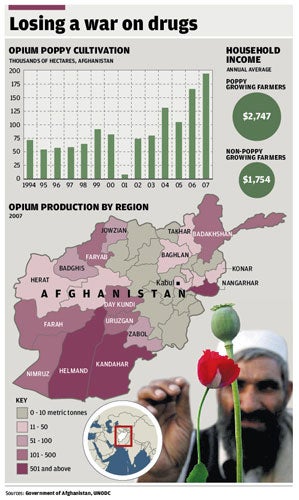

In 2008, in Afghanistan, 157,000 hectares (610 square miles) were given over to growing poppies and they produced 7,700 tonnes of opium. Production has soared to such an extent in recent years that supply is outstripping demand. Global demand is only about 4,000 tonnes of opium per year, which has meant the price of opium has dropped. in Helmand alone, where most of Britain's 8,000 troops are based, 103,000 hectares were devoted to poppy crops. if the province was a country, it would be the world's biggest opium producer.

In 2007, the UN calculated that Afghan opium farmers made about $1bn from their poppy harvests. The total export value was $4bn – or 53 per cent of Afghanistan's GDP.

Is it getting better or worse?

There was a 19 per cent drop in cultivation from 2007 to 2008, but bumper yields meant opium production only fell by 6 per cent. Crucially, the drop was down to farmers deciding not to plant poppies, and that was largely a result of a successful pre-planting campaign, led by strong provincial governors, in parts of the country that are relatively safe.

Only 3.5 per cent of the country's poppy fields were eradicated in 2008. High wheat prices and low opium prices are also a factor in persuading some farmers to switch to licit crops.

In Helmand, one of the most volatile parts of Afghanistan, production rose by 1 per cent as farmers invested opium profits in reclaiming tracts of desert with expensive irrigation schemes. Opium production was actually at its lowest in 2001. The Taliban launched a highly effective counter-narcotics campaign during their last year in power. They used a policy of summary execution to scare farmers into not planting opium. Many analysts attribute their loss of popular support in the south, which contributed to their defeat by US-led forces in late 2001, to this policy.

How are the drugs linked to the insurgency?

The Taliban control huge swaths of Afghanistan's countryside, where most of the poppies are grown. They tax the farmers 10 per cent of the farm gate value of their crops. Antonio Maria Costa, head of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, said the Taliban made about £50m from opium in 2007.

They also extort protection money from the drugs smugglers, for guarding convoys and laboratories where opium is processed into heroin. The UN and Nato believe the insurgents get roughly 60 per cent of their annual income from drugs. The Taliban and the drug smugglers also share a vested interest in undermining President Hamid Karzai's government, and fighting the international forces, which have both vowed to try and wipe out the opium trade.

What about corruption?

The vast sums of drugs money sloshing around Afghanistan's economy mean it is all too easy for the opium barons to buy off corrupt officials.

Most policemen earn about £80 a month. A heroin mule can earn £100 a day carrying drugs out of Afghanistan. Most Afghans suspect the corruption reaches the highest levels of government. President Karzai is reported to have called eradication teams to halt operations at the last minute for no apparent reason.

When an Afghan counter-narcotics chief found nine tonnes of opium in a former Helmand governor's compound, he was told not burn it by Kabul – but he claims he ignored the order.

President Karzai's brother, Ahmed Wali Karzai, is widely rumoured to be involved in the drugs trade – an allegation he denies. The New York Times claimed US investigators found evidence that he had ordered a local security official to release an "enormous cache of heroin" discovered in a tractor trailer in 2004. Privately, Western security officials admit they suspect that a number of government ministers are drug dealers.

Where does that leave the international community?

Right across Afghanistan, the government is corrupt and Afghans are fed up. The police organise kidnappings. Justice is for sale. Violence is spreading and people don't feel safe. The progress promised in 2001 hasn't been delivered.

Education is a rare success. There are now more than six million children at school, including two million girls, compared with less than a million under the Taliban.

But the roads which link the country's main cities aren't safe. Taliban roadblocks are increasingly normal. UN convoys are getting hijacked.

A report published by 100 charities at the end of July warned violence has hit record highs, fighting is spreading into parts of the country once thought safe, and there have been an unprecedented number of civilian casualties this year.

General David McKiernan, the US commander of almost all the international forces in Afghanistan, insited to journalists at a press conference on Sunday that Nato isn't losing. The fact he had to say it suggest public perception is otherwise. He also said that everywhere he goes, everyone he speaks to is "uniformly positive" about the future. Those people must be cherry-picked.

Crime in the capital, Kabul, is rising. The Taliban broke 400 insurgents out of Kandahar jail this summer, and they attacked the provincial capital in Helmand last weekend. People are frustrated at the international community's failures and scared that the Taliban are coming back.

What does that mean for the future?

President Karzai has touted peace talks with the Taliban through Saudi intermediaries. The international community maintains it will support the Afghan government in any negotiations, but privately diplomats admit that if they opened talks tomorrow they would not start from a "perceived position of strength".

General David Petraeus is about to take command at CentCom, which includes Afghanistan, and he is expected to focus on churning out more Afghan soldiers and engaging tribes against the insurgents.

Meanwhile, in Pakistan, it remains to be seen whether Asif Ali Zardari will rein in his intelligence service and crack down on the Taliban safe havens in the Pakistani tribal areas, which they rely on to launch attacks in Afghanistan.

There are also elections on the horizon. The international community is determined that they must go ahead, despite the obvious security challenges, and anything the Afghan candidates do should be seen in the context of securing people who can deliver votes.

Does the war on drugs undermine the war on terror?

Yes

*Working to eradicate poppies will remove farmers' best source of income and turn them against Nato

*Using resources to fight against the entrenched poppy trade diverts them from the war with the Taliban

*Corruption in government means that battling opium turns the mechanism of the state against our forces

No

*In the end, an Afghanistan without opium production will be much less prone to the influence of the Taliban

*Money from the international drugs trade may find its way to terrorists outside of Afghanistan

*Removing the source of corruption will strengthen the country's institutions in the long term

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments