Shunga exhibition defies 'pornography' taboos to expose Japan to its erotic past

Given the glut of online smut, it seems odd that a collection of woodblock prints still has the power to get pulses racing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

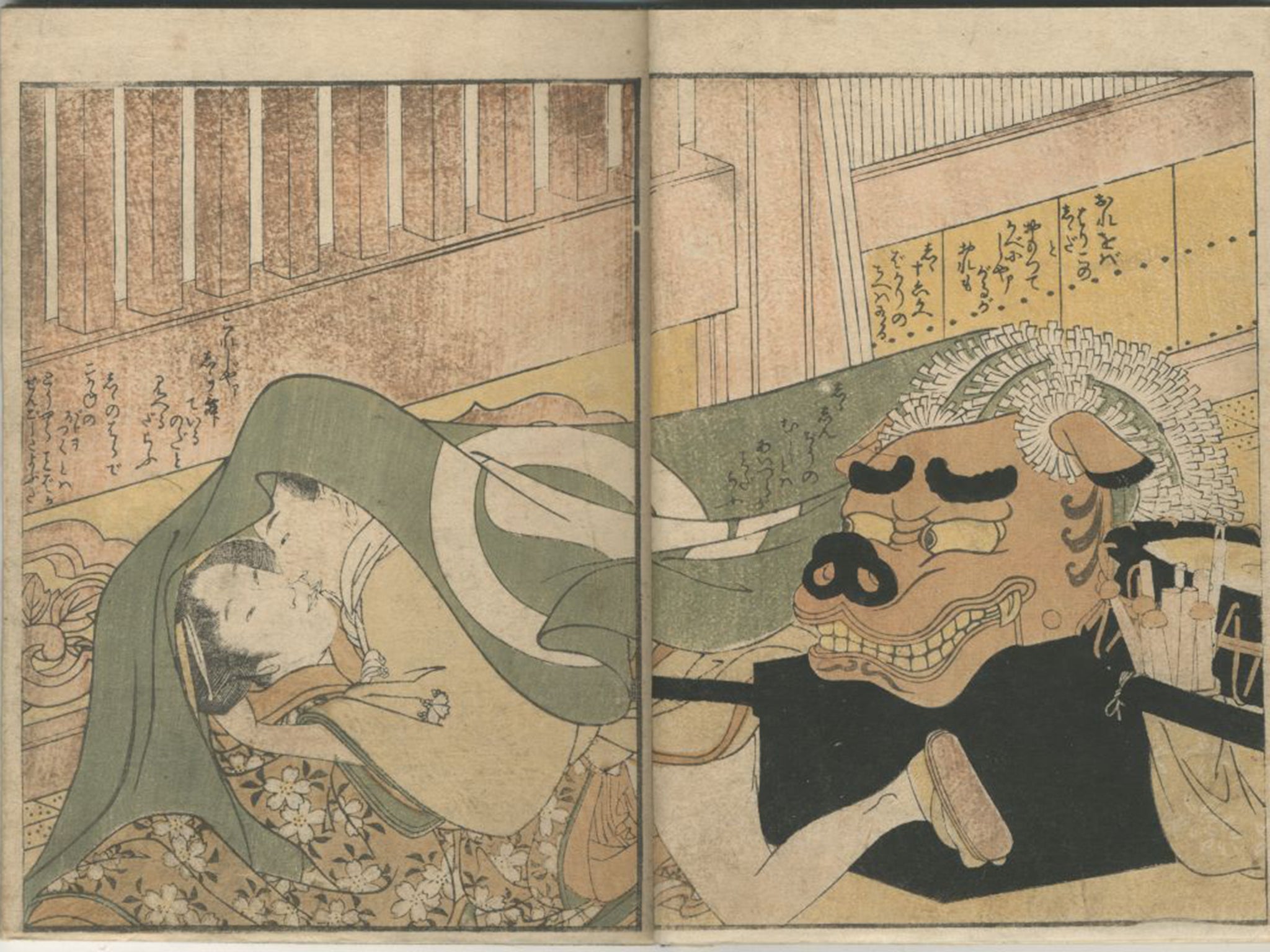

Your support makes all the difference.Off a leafy backstreet in Tokyo, middle-aged people have come to look at couples with outsize genitalia grapple in brothels and inns. In one print, a woman writhes in ecstasy as an octopus performs oral sex on her. In another, a cat prepares to scratch the testicles of a man in the throes of sexual pleasure. Men couple with courtesans, animals and even statues.

Shunga is not for the faint-hearted. Still, given the glut of online smut, it seems odd that a collection of old Japanese woodblock prints still has the power to get pulses beating faster. But shunga, meaning “spring pictures”, showing sometimes spectacular sexual contortions on the futon, come loaded with the power of taboo. As a result, they have largely been out of sight in Japan for decades – until now.

A small museum has defied the taboo. Billed as Japan’s first full shunga exhibition, many of the 133 items have been culled from the British Museum, which ran its own show in 2013 (one tabloid dubbed the exhibition “Shunga Bunga”). Despite that seal of approval from the British art world, Japanese galleries still had a case of the vapours when the offer to host the exhibition came: most turned it down.

Hand-painted shunga were exclusively enjoyed by the Japanese upper classes in the 1600s before technology unleashed them on the hoi polloi. Woodblock, the mass production technique of the day, created thousands of prints. The underground art mocked official Confucian values and social mores: one depicts a widow who has gone to a Buddhist temple for solace, for example, being ravished by a priest.

But their main purpose was sensual, not political, says Timothy Clark, the head of the Japanese section at the British Museum. The prints showed sex as pleasurable and funny, which is why they could not survive the clash with uptight Victorians arriving in Japan in the late 19th century. “There was a lot of surprise on both sides,” he says.

Japanese modernisers, eager to earn a seat in rich nations club, clamped down and shunga was shoved out of sight for nearly a century. Shame and a new-found prudishness resulted in many going up in flames or disappearing into private collections. For years, police confiscated prints and censors scribbled out or obscured the offending bits.

Museums think it is shameful to have these paintings in their collections

“There has been a taboo on shunga since the Meiji era [1868-1912],” says Akiko Yano, an art historian at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. “Museums think it is shameful to have these paintings in their collections. It has not been treated as an academic subject – Japanese people like to think of things as official and shunga wasn’t.”

The Eisei Bunkyo Museum, run by the Hosokawas, an old samurai clan, reckons it has the stuff to rehabilitate an art form that went on to influence Picasso and Rodin. It’s time for Japanese to appreciate the real shunga, explains Morihiro Hosokawa, a former prime minister, in his foreword to the exhibition. Most Japanese, at least: the under-18s are banned from taking a peek.

One problem that gave bigger galleries cold feet is shunga’s frank depiction of genitals (Japanese censors still pixilate the nether regions, even in pornography). In truth, says Ofer Shagan, a businessman who owns the world’s largest shunga collection, technology has long since bypassed the censors: books of prints sell in droves.

The authorities are again behind the curve, he laments. And they still mis-label shunga, he adds: ”People will think it is pornography. There is so much more to it than that.”

Still, shunga fans say the exhibition, which runs until December, is good news. Larger galleries and private collectors such as Mr Shagan can now pull prints out of dusty warehouses without worrying about a raid by the police.

Japanese people will finally be able to take pride in a neglected corner of their own rich cultural history, says Ms Yano. It’s ironic, she says, that they again needed a prod from abroad to make this possible.

“Japan somehow needs reassurance from outside to see the value of their past cultures.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments