Poisoned legacy of Bhopal: Campaigners call on Dow Chemical to answer criminal charges, 31 years after toxic explosion

In 1984, an explosion at a pesticide plant exposed 500,000 people to a cloud of toxic gas in India. The tragedy killed 25,000 people and activists claim it is causing deformities in children today. Andrew Johnson reports on the victims’ fight for justice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few people will pay much attention to the handful of women who will sit in the public gallery of an unfashionable Indian city’s lower court this Saturday morning. However, the families of Bhopal, three generations of them, will be interested in every face that comes and goes.

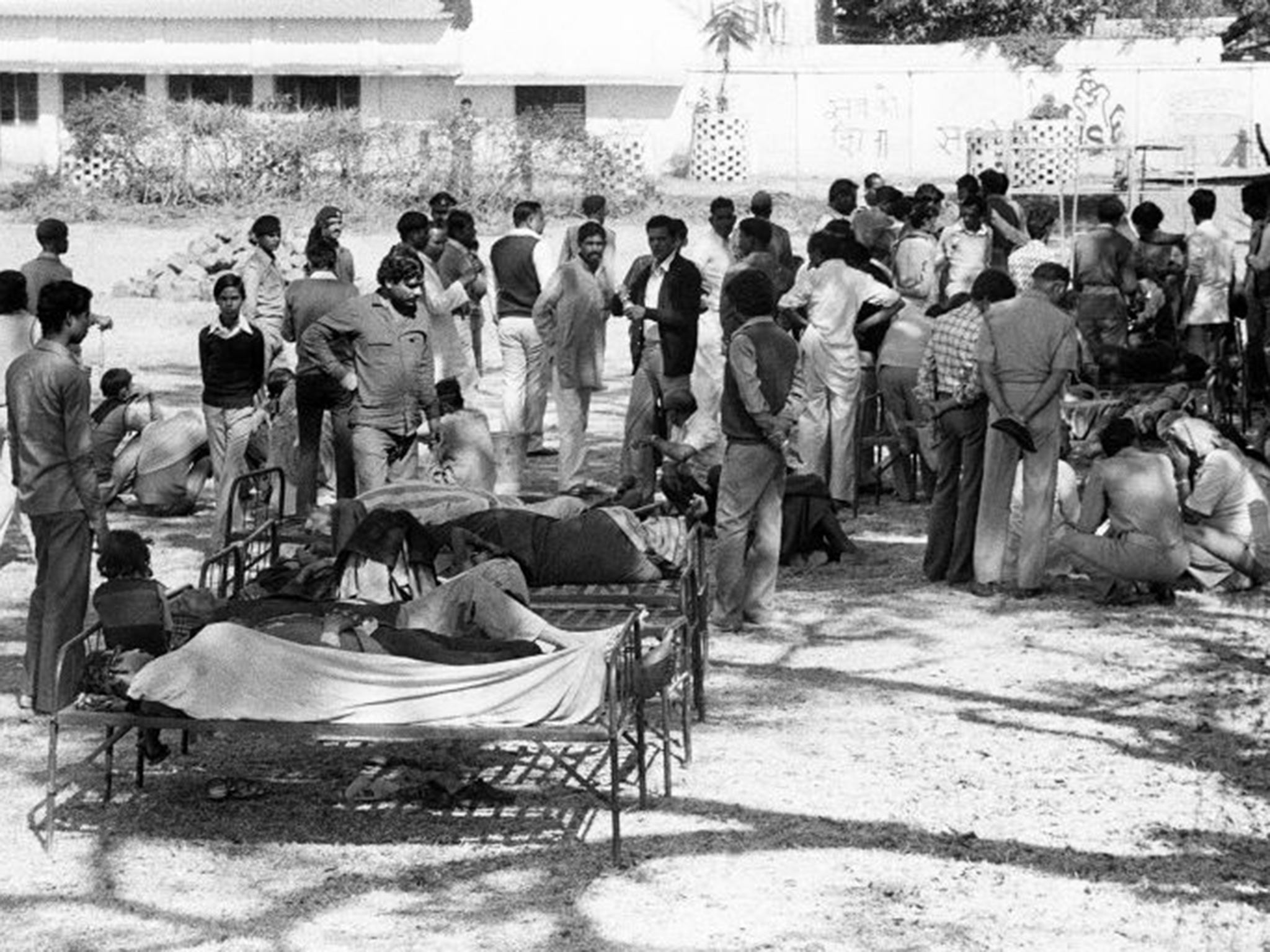

They will remember how, 31 years ago, the state capital of Madhya Pradesh experienced the world’s worst industrial accident when a Union Carbide pesticide plant exploded, sending 42 tonnes of poison, methyl isocyanate, into the air and down into the slums next to the factory.

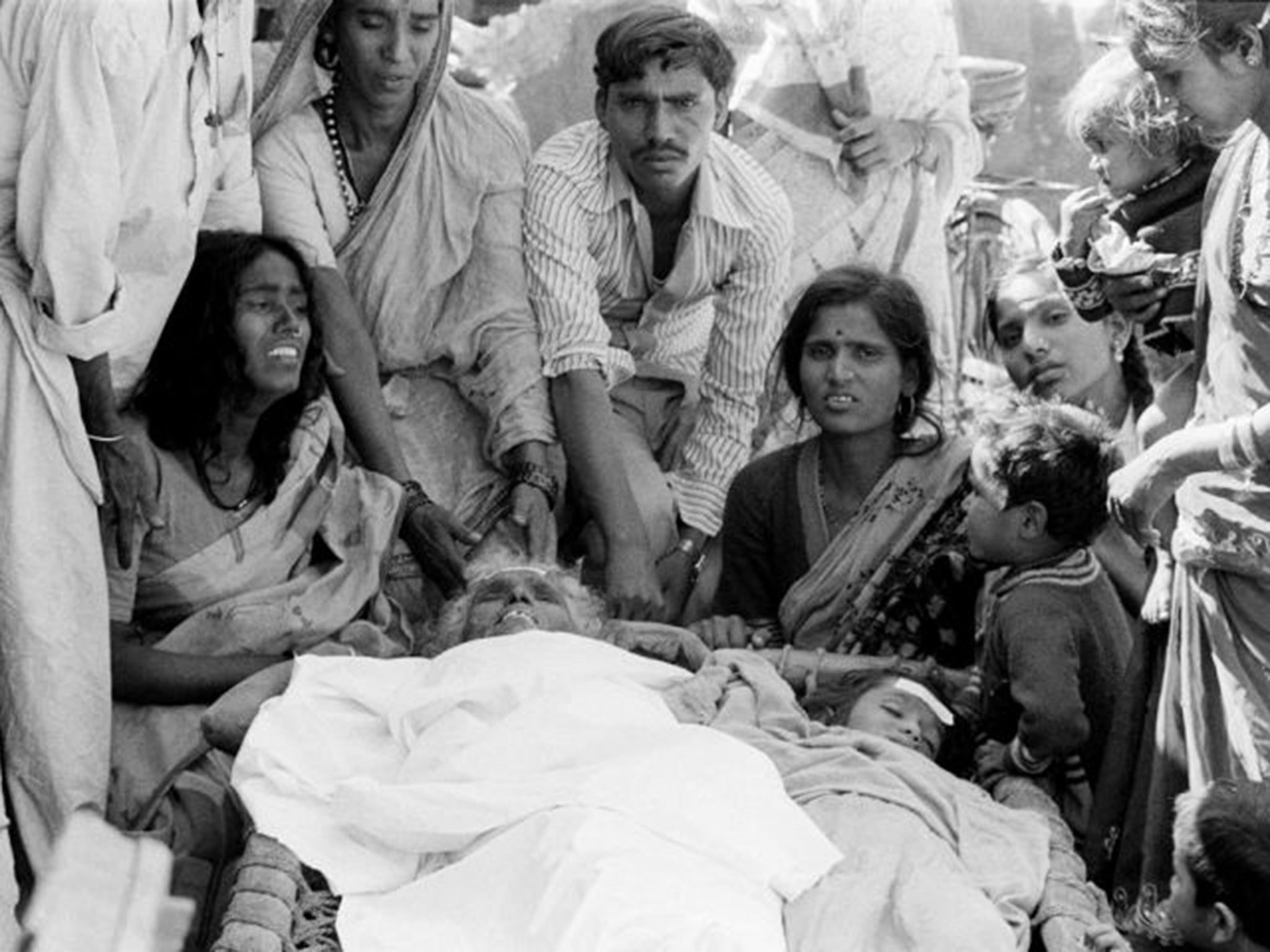

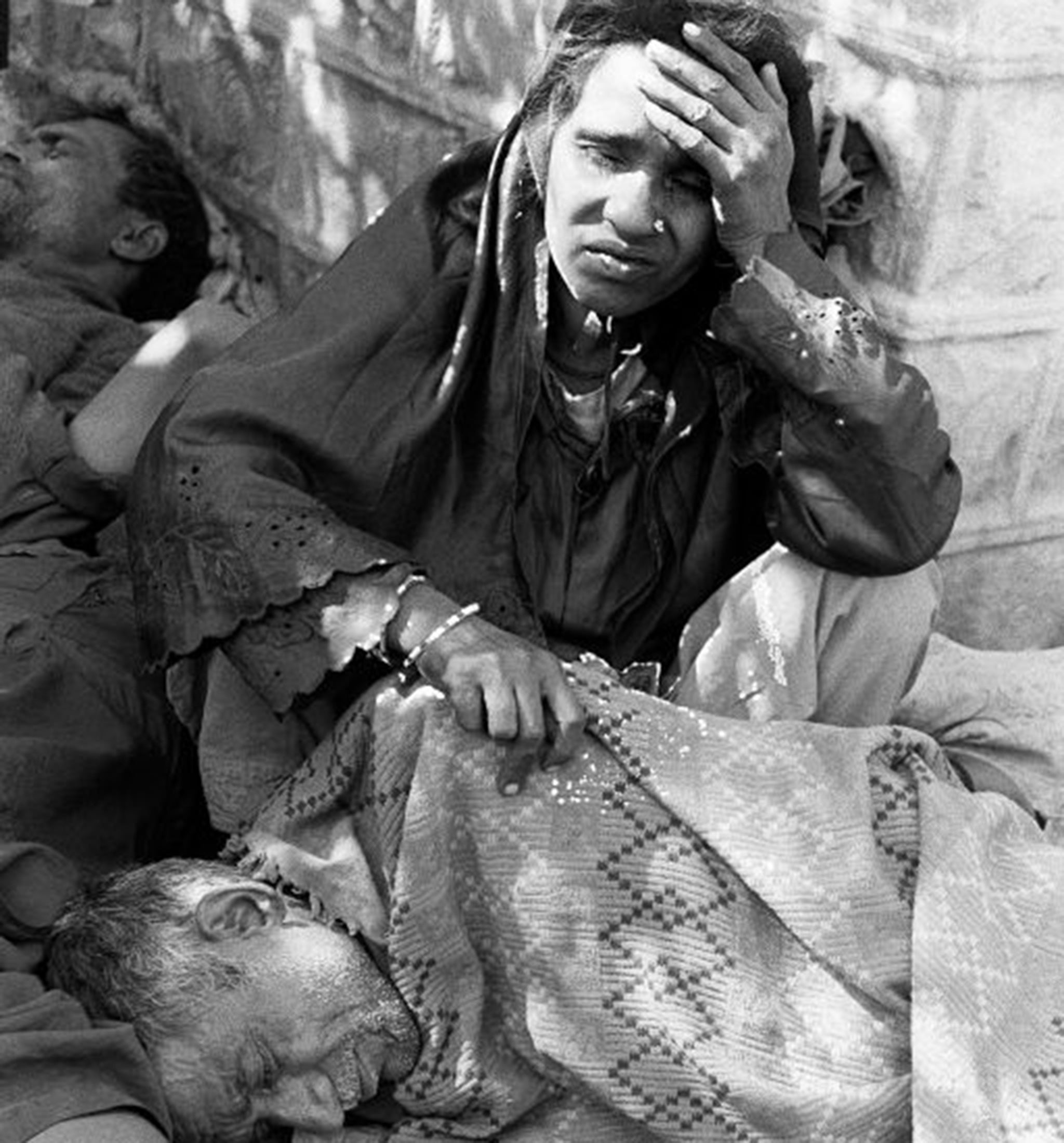

Then, their lungs and their eyes burned. Eight thousand were dead within a week. The explosion killed at least 25,000 people altogether and left tens of thousands with lifetime injuries.

The legacy of the Union Carbide disaster is still felt today, in the twisted limbs, brain damage and musculoskeletal disorders doctors continue to report in children. Its legacy will bring the women of Bhopal, and the campaign groups, to the court this morning.

They hope to see a representative of US pharmaceutical behemoth Dow Chemical arrive to answer for a disaster which was presided over by a company it did not own at the time of the explosion. Their hope appears unlikely to be answered. “Frankly, I’m amazed they have such faith in the (judicial) process,” said Avi Singh, lawyer for the Bhopal campaigners planning to attend court.

The lack of action over the disaster has prompted renewed calls for the Indian government to act. It has never seriously been doubted that the explosion was the result of poor safety standards. Assigning liability for the disaster has proved more difficult.

The parent company of Union Carbide denied it was responsible for the soil and water pollution that followed the explosion. Campaigners claim the contamination continues to cause learning and physical disabilities today.

In 1989, Union Carbide paid a $470m settlement to the Indian government. It was well short of the $3.3bn in damages requested. Union Carbide was bought by Dow Chemical 16 years after the disaster.

Warren Anderson, who died last year, aged 92, was Union Carbide chief executive at the time. He was declared an absconder from justice by the Indian courts after failing to answer a summons for culpable homicide.

Bhopal, which was seen as a symbol of a new industrialised India, generating thousands of jobs for the poor and producing relatively cheap pesticides for farmers, is long gone. India has moved on.

Mr Singh, who represents the Bhopal victims, told The Independent that the Indian justice system was to blame for the failure to address today’s legacy in Bhopal. He said far more could be done to address the campaigners’ demands.

In particular, he claimed India’s Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) had failed to pursue a criminal prosecution against the company that now owns the remains of Union Carbide, Dow.

“The CBI has acted very slothfully and should be hauled up [for] their lack of prosecution,” said Mr Singh. Dow has continued to deny any responsibility for its subsidiary.

Union Carbide has been branded an “absconder from justice” and the Indian courts have demanded that Dow produce its officers in court to answer the criminal charges of culpable homicide.

Dow blocked a summons in 2005; the block was overturned in 2012 and Dow was ordered to appear in court. That failed, because nobody came. Again, Dow did not appear for a rescheduled hearing last March. Mr Singh was not hopeful Dow would appear in court today. “I don’t expect them to turn up,” he said.

Campaigners hope that if Dow officials fail to appear, the firm will be declared an absconder from justice, which would ban it from doing any business in India. They have accused Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi of being apathetic to the demands of campaign groups. He has been almost silent on the issue.

Now, there is even more urgency for the campaigners, who are supported by The Bhopal Medical Appeal. Earlier this month, Dow announced “a merger of equals” with the chemical giant DuPont, to create a business, among the world’s biggest, worth $130bn. The new company, DowDuPont, will be split into three companies within two years, adding more corporate layers between the people of Bhopal and Union Carbide.

Mr Singh admitted it will make matters more difficult. “We’ve seen that with Union Carbide and Dow. It is something not just for Bhopal – the idea that corporations can mutate their identities and leave their liability behind is something that needs to be addressed.”

Dow said there was no case to answer. It pointed out that it never owned or operated the Bhopal plant. When Union Carbide was subsumed into Dow, in 2001, the larger firm did not assume its liabilities, Dow said.

Dow argued that the case today has been brought by a campaign group rather than the government. “It is not a summons nor does it make TDCC [The Dow Chemical Company] a party to the proceeding.” Efforts to directly involve Dow in legal proceedings are, according to the company, “without merit” and Indian courts have no jurisdiction to compel Dow to take action.

“If they don’t show up there are elements of the law that have been violated, including obstruction of justice, and that is something we intend to pursue. It’s been too many years and it’s about time they answered this offence,” Mr Singh said.

“Frankly, it is something we should be ashamed of, our inability to find an accused is ridiculous. There have been no diligent efforts on behalf of either the prosecution or the judiciary to bring this to book. One hopes the judiciary and prosecution step up. If they do there are sufficient tools to allow this to proceed.”

Satinath Sarangi, of the Bhopal Group for Information and Action, hoped the Indian authorities would summon “the courage to take effective legal actions against the corporation”.

“Seven members of my family have died because of the gas tragedy,” Rashida Bee, a trustee of the Chingari Rehabilitation Centre, a clinic to help victims of the tragedy, told The Independent on the 30th anniversary of the disaster. “Every day I have to take medicines. I have constant headaches and pains in my limbs.”

A soiled sticker found in the plant’s dusty control room after the disaster read: “Safety is everyone’s business.” The women in court will hope – against their expectations – to hear officers from one of the world’s biggest chemical businesses discuss that subject further.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments