India polio-free for three years: meet the people fighting to keep it that way

There were just 37 cases of polio worldwide in 2016, in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nigeria. Polio campaigners say the world is ‘on the brink of a historic milestone’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rabiya had barely taken her first steps when she caught polio. Her young legs twisted inwards and became limp, leaving her unable to walk at all.

She is now 18 and dreams of becoming a teacher, despite the heavy plastic braces supporting her fragile limbs – braces which, had she been born just one generation later, she may never have needed.

Her six siblings helped her get around as she grew up, says Rabiya, but she wants to be more independent. She is dressed smartly in royal blue, sitting up in bed at St Stephen’s hospital in Delhi, where she is having a series of operations in the hope of one day moving by herself.

India was declared polio-free in 2014, an achievement reflected in the rising age of the polio survivors treated at St Stephen’s.

“For the last five or six years, I’ve been seeing fewer younger patients,” says Dr Mathew Varghese, who runs the hospital’s dedicated polio ward – the only one in the country. “I never thought that would be possible.”

Polio mainly affects children under five and can cause rapid paralysis and sometimes death. Once a worldwide scourge, concentrated vaccination efforts have caused the total number of cases to drop from about 350,000 in 1988 to to just 37 last year, in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria.

“The youngest patient I saw last year was a seven-year-old boy,” says Varghese, adding that teenagers and young adults are more difficult to operate on “because their joints have been stiff for so long”.

Global health bodies and governments are optimistic that the world’s last ever case of polio could be recorded this year. There has been one so far, an 11-month old girl in Afghanistan.

Serious challenges, including violent attacks on health workers by Islamists, poor routine immunisation coverage and rumours the vaccine causes impotence make this a precarious possibility. But if India can do it, why not the world?

“India was probably the most challenging place on earth to eradicate polio,” says Dr Pankaj Bhatnagar of the World Health Organisation, which has worked closely with the Indian government, Rotary International, Unicef, the Gates Foundation and the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention to implement the 30-year vaccination drive.

The sheer number of people in India combined with low sanitation levels means “conditions are ripe for the polio virus to transmit through the faecal route,” says Bhatnagar. “There are places in India that are hard to reach – people living in forests, along riverbanks, in mountainous areas in the north east or the flat plains of Bhatar, where there are no roads”.

Even in crowded Delhi, it’s a challenge to make sure every child is seen on National Immunisation Day, a vast operation that aims to deliver polio drops to 172 million under-fives in one go.

Children jostle to reach the front of the queue at one of the country’s 700,000 vaccination booths. This one is in a small health centre amid ramshackle houses painted in pale pinks and bright blues, with washing strung up between them. A young woman of about Rabiya’s age crouches to rinse her hair from a small metal bucket, the dirty water trickling away into an open sewer.

Among the two and a half million people delivering the vials of vaccinations to the booths in cool boxes, administering two drops to each child, and then going from house to house the next day to make sure no one is missed, are some 100,000 Rotary volunteers. The slogan on their bright yellow bibs has been recently updated to say: “Keep India Polio Free”.

A handful have travelled at their own expense from the UK, Japan, Belgium, Sweden and the US to support the charity’s long-running global polio eradication programme, launched in 1985 as the first campaign of its kind. “We have to finish the job. We’re on the brink of a historic milestone,” says Eve Conway, President of Rotary Great Britain and Ireland. “When we do rid the world of polio, it will save us billions of pounds. And that money can be used to tackle other diseases.”

Five-year-old Manu, wrapped in a woollen cardigan – we may be in India, but it’s still January – shyly shows me her little finger, painted purple to show she has received the drops. She’s done this before, and unlike some of the younger children, didn’t squeal at its bitter taste.

Multiple vaccination rounds take place each year to ensure maximum coverage, but their frequency is now dropping, says Dr Sucheta Bharti. She works in a maternity clinic which plans and distributes the vaccines in Madipur in west Delhi, where on my way to meet her I spot a round-eyed kitten nestling among piles of fresh ginger on one of the many carts lining the streets.

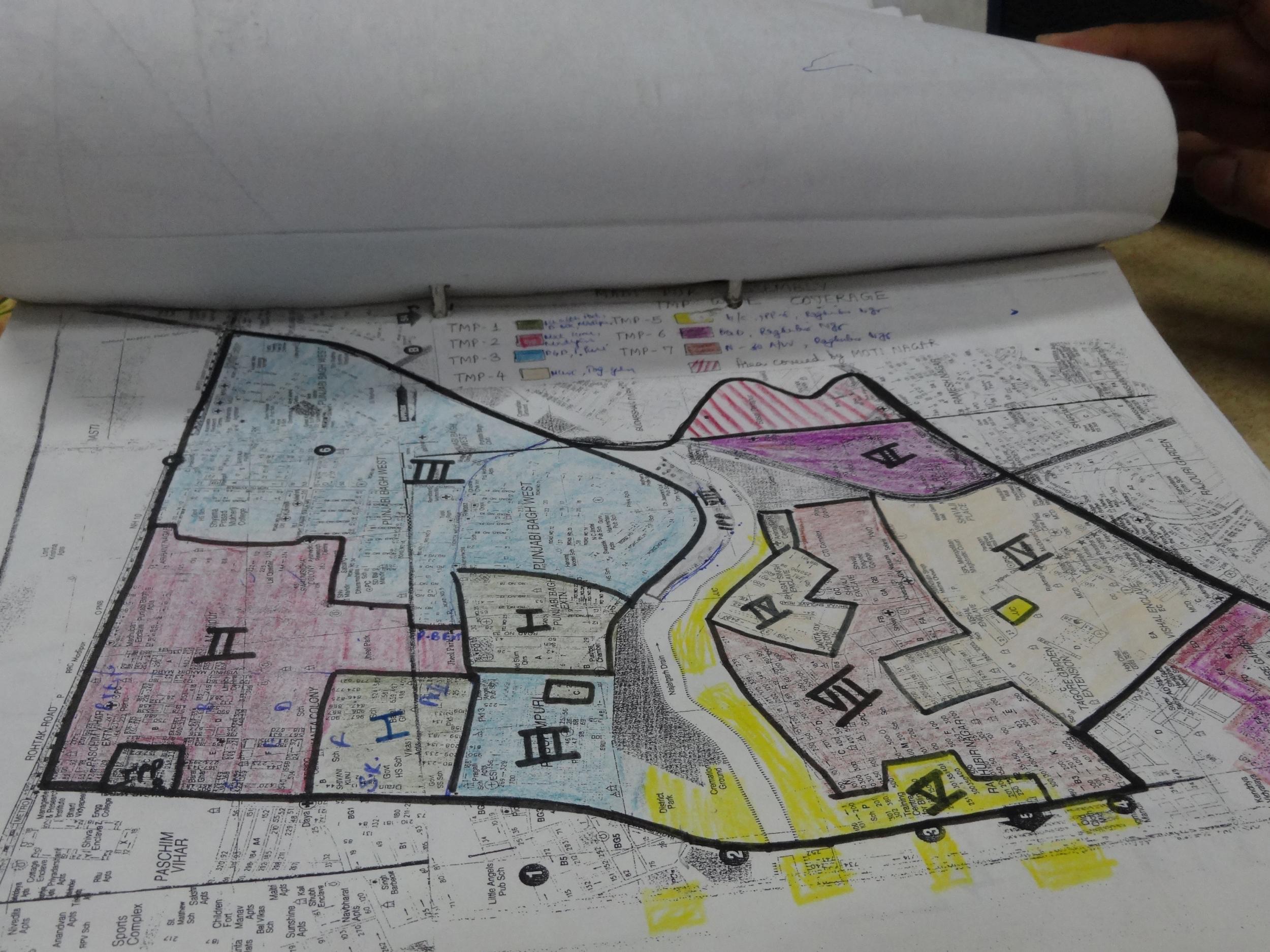

Bharti shows me the clinic’s hand-drawn, colour-coded plan of the local area and a detailed record of who lives where. At a nearby health centre, a simple, narrow room covered in posters of food groups and hand-washing diagrams, a group of children who outnumber the average reception class chant together and are reminded of the importance of the upcoming immunisation day.

The structures put in place by the polio programme help to reinforce maternity care and other important initiatives, says Bharti. During the Ebola epidemic, Indian medical teams travelled to Africa to share their expertise. When India’s last case of polio was detected in 2011, she and her team were doing about 10 rounds in a year. “Now we’re managing with five to six rounds,” she says. “This year we are planning four rounds in Delhi, depending on if the number decreases in neighbouring countries.”

And if a new case of polio is discovered in India? “We won’t let that happen. That is not acceptable,” she says. “Everyone has worked so hard at the ground level and also at the higher level. Even if a case comes from elsewhere, we'll make sure it does not spread to other children. This phase is even more important than what we were doing when cases were still happening.”

There may soon be a shift in some aspects of the programme’s delivery, however. The Indian government has announced it will cut some ties with the Gates foundation and partially fund the country’s immunisation programme itself – a move linked to a broader push against foreign-led non-governmental organisations working in key policy areas.

Senior health ministry official Soumya Swaminathan told Reuters that the government had decided to manage its technical arm of the immunisation programme in Delhi, by itself as “there was a perception that an external agency is funding it, so there could be influence”, although she said no instances of such influence had been found. A spokesperson for the Gates Foundation said its grant for the programme ends this month and it was in “advanced stages of discussion” with the government about the next steps for collaboration.

Bharti and doctors across the country are also now required to administer an injected polio vaccine as part of routine childhood immunisation as well as the drops, which have been linked to a small number of cases of vaccine-derived polio. This occurs when the weakened live virus used in the vaccine mutates into a form that spreads infection, instead of prevention.

“The big push has been to get rid of the wild poliovirus, which has been around for millennia,” says Jay Wenger, head of the Gates Foundation’s polio programme. “The issue of vaccine-derived poliovirus is essentially a side effect of the vaccine we’re trying to use to get rid of wild poliovirus.”

Last year, five polio cases were caused by a “vaccine-derived” virus. Last April, all of the countries using the oral polio vaccine changed to a different formula, which doesn’t include a strain that has been eradicated in the wild but was more likely to mutate into the disease-causing type. A global shortage of injectable polio vaccine has placed a stumbling block in the way of this plan, and the three countries where the wild virus is endemic are at the top of the list to receive it, while countries like India are training nurses to give micro-doses, essentially rationing the vaccine.

At first, the health workers encountered resistance from families, says Bharti – not just from the Muslim population, but also from the Rajasthani community. In a rural area in Uttar Pradesh, parents pushed health workers off roofs when they came to immunise children, resulting in fractures.

But through working with religious and community leaders, attitudes have changed in India. This is slowly becoming the case in Pakistan and Afghanistan too, but vaccinators continue to risk their lives. Last year, seven policemen guarding polio workers were killed by Islamist gunmen in Pakistan, while 15 people were killed in a bomb attack on a vaccination centre.

The Taliban has violently opposed vaccination efforts, calling them a Western conspiracy to sterilise children. Rejection of the programme intensified when it emerged that the CIA had set up a fake hepatitis vaccination campaign in Afghanistan during the 2011 search for Osama Bin Laden. “There is certainly fear. Anyone could be attacked. The workers are heroes, especially female workers who go from door to door,” said a doctor working with an international health organisation in Pakistan, who did not want to be named for security reasons.

Almost everyone I speak to in Delhi knew someone with polio while they were growing up. At a polio awareness rally organised by a school in the west of the city, Deepti, a 20-year-old teacher, says she remembers when her neighbour, who was four years older than her, caught the disease. She couldn’t hold her birthday cake properly at her birthday party, and now she is dependent on her parents.

Marching through the streets of Delhi, holding up motorcycles packed with passengers and bringing great grandparents with their small children out into the street to watch, the students hold handmade banners saying “Now more than ever, stop polio for ever” and “Keep your health pristine! Get the vaccine!” Getting rid of polio won’t solve all of India’s problems, but the future looks bright. As Deepti remarks: “Some of these students won’t ever know what polio is.”

Additional photography by Rotary International India National PolioPlus Committee. The polio ward and rehabilitation surgery at St Stephen's hospital is funded through the Rotary Foundation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments