How satellite imagery may finally uncover the tomb of Genghis Khan

The blood-thirsty warlord decreed nobody was ever to know where he was buried. True to his word, the location, somewhere in the vast terrain of modern Mongolia, has remained secret for 800 years. Until now, it seems

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

When Genghis Khan died, he didn’t want to be found.

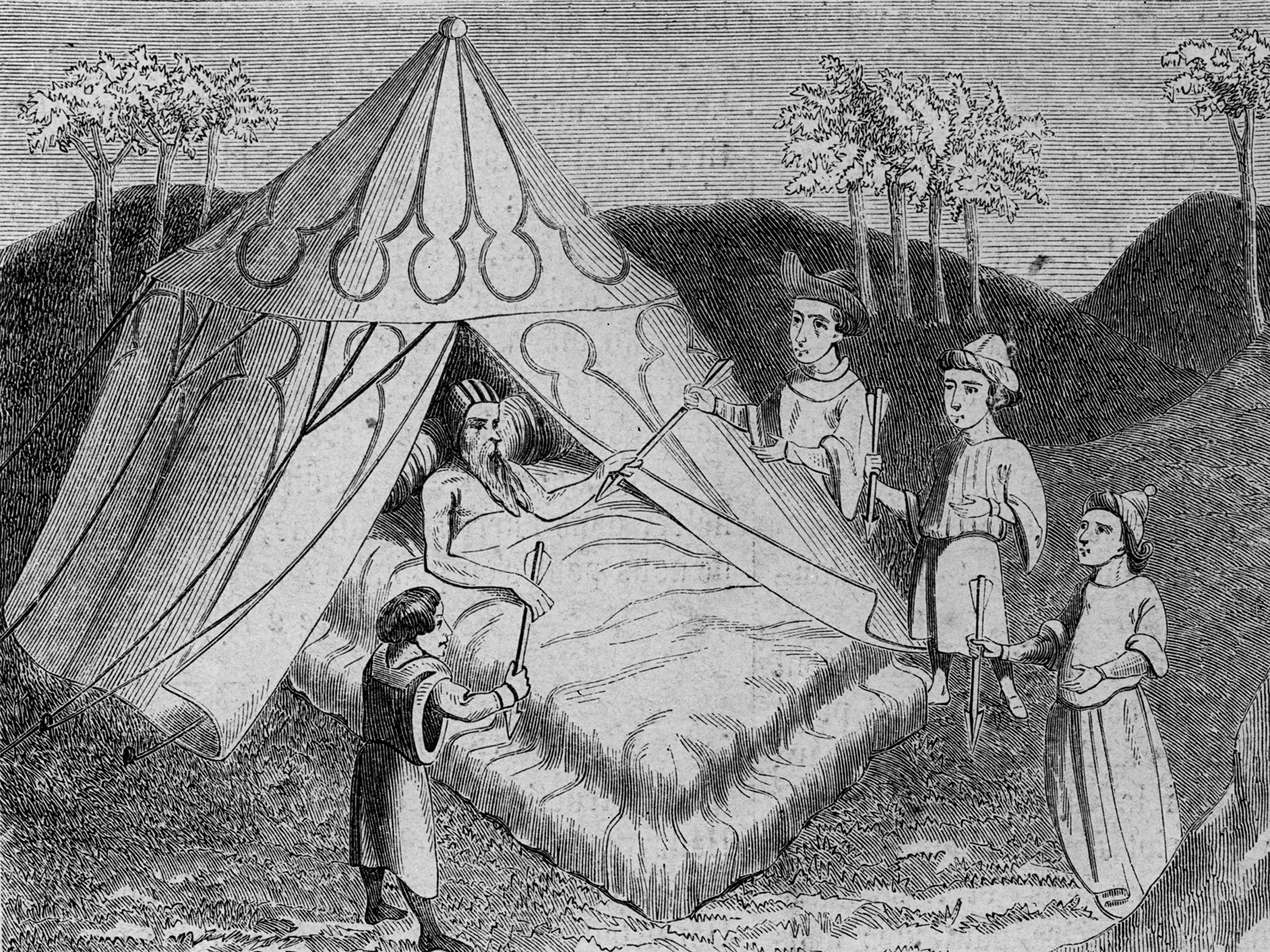

So soldiers in his burial party butchered anyone they saw on their way to his burial tomb. Then they killed the people who built the monument. Then, finally, they killed themselves.

Who knows whether the perhaps apocryphal tale is true but even today, nearly 800 years after he death of the greatest conqueror the world has ever known, the location of his tomb remains unknown.

Many people have tried to find it, from archaeologists who uncovered Genghis Khan’s palace to a lawyer from Chicago who led an expedition to 60 unopened tombs in the Mongol warlord’s realm.

The quest is for history – and for riches. According to Mongolia Today, incredible treasures were buried with Genghis Khan from every corner of his vast empire and, as one researcher told the Associated Press, “if we find what items were buried with him, we could write a new page for world history”.

“Ultra-high resolution satellite imaging enables a new paradigm in global exploration,” said a study published last week in the journal Plos One. But the breadth of the search was so daunting and vast that researchers with the University of California at San Diego, led by Albert Yu-Min Lin, have outsourced the search to the general public.

“This is a needle in a haystack problem where the appearance of the needle is unknown,” wrote Mr Lin, who has been described as a “modern-day Indiana Jones” and has been photographed dramatically riding horses across the Mongol expanse. So “we charged an online crowd of volunteer participants with the challenge of finding the tomb of Genghis Khan, an archaeological enigma of unknown characteristics widely believed to be hidden somewhere within the range of our satellite imagery”.

One of the problems, however, is that there was so much land to study. The sweep of Genghis Khan’s empire, which began when he united Mongolia’s warring tribes in the early 13th century, is dizzying to contemplate. It first subsumed all of what is modern-day Mongolia before spilling across Asia on the might of the Mongol invasions, conquering terrain from China to the gates of western Europe by the turn of the century.

Many now suspect Khan’s final resting place is much closer to the roots of his power – in Mongolia itself, near the site of his palace, around 150 miles east of the nation’s capital, Ulan Bator.

So, in a partnership with National Geographic, Mr Lin’s team constructed a landscape of more than 84,000 tiles that spanned more than 6,000 sq km and launched what they called a “virtual exploration system” in 2010. The task for participants: tag anything that looks like it could be an “archaeological enigma that lacks any historical description of its potential visual appearance’’.

It was essential to get help, the magazine said: “A single archaeologist would have to scroll through nearly 20,000 screens before covering the whole area.” Still, no one expected they would get so much of it. More than 10,000 people gave it a go, tagging anything they thought looked like a location where a great Mongol warlord would want to rest in peace.

In all, they clocked more than three years’ worth of work – 30,000 hours – and generated more than two million tags. From that number, the researchers have culled 100 locations for further inquiry and identified 55 “potential archaeological anomalies” that ranged from the Bronze Age to the Mongol period.

So far, no Khan yet. But the search is complicated by a number of factors unique to the quest for Khan’s tomb. As explained by Vice Media’s Ben Richmond, the Mongols absolutely hate archaeologists trampling on their turf disturbing the nation’s most holy sites.

In fact, the spot where a lot of people thought Khan was buried is actually one of the country’s most sacred spots. It’s called Ikh Khorig, which translates literally to the “great taboo”, but is often called the “forbidden zone” by outsiders.

Mr Lin – who reports describe as “obsessed” with Genghis Khan and finding his tomb – also searched the forbidden zone but found nothing. “The team pushed its way through the thick, boar-infested brush surrounding it and clambered to the top,” as National Geographic described one of the expedition’s analyses. “A test probe, however, revealed that the hill was just a hill.”

But now, thanks to his crowdsourcing study, he has a whole new range of potential sites to explore to try to discover the tomb. Still, how to side-step Mongolia’s reservations about expeditions?

“Mongolians detest any attempt to touch graves, or even wander around graveyards,” Mongolia Today said. “According to ancient tradition, burial spots are forbidden areas in which no one is allowed.” So he hopes to find it from space – and now he says he can.

©The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments