Battle for hearts and votes reaches Taliban heartland

The ballots in Pashtun region could settle next week's crucial poll. Kim Sengupta reports from Helmand

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is a small town in Helmand, with nothing much to show for itself except decaying relics of American investment from the days of the Cold War and a landscape of unusual greenery amid the vast arid plains of southern Afghanistan.

But yesterday, Char-e-Anjir was the subject of much attention when it hosted a visit by VIPs from Kabul and the provincial capital, Lashkar Gar, who were accompanied by the international media. A shura, or community meeting, was held for local people and a ceremonial lunch for community elders.

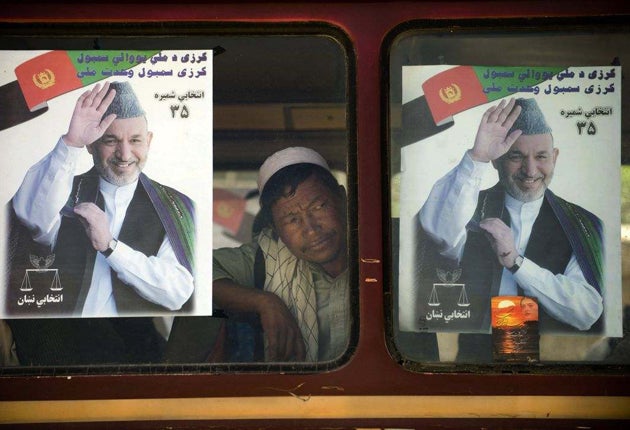

The spotlight was a precursor to the Afghan presidential election. With just over a week to go before the polls and the race now anything but an easy romp home for Hamid Karzai, what happens here in the Pashtun belt has become acutely important. How the people here vote and how many vote, will decide the outcome.

Char-e-Anjir is of totemic importance in an election taking place in a country at war. The area slipped under Taliban control before British troops took it back through Operation Panther's Claw which, alongside an American offensive, was designed to improve security in a lawless region so thatabout 80,000 people could vote.

The registration and mobilisation of voters in the south is taking place alongside last-minute operations by British and American forces to drive the Taliban away from some of their remaining strongholds in the Helmand river valley.

Yesterday, helicopter-borne US Marines, backed by Harrier jets from the UK, stormed the town of Dahaneh, taking it after an eight-hour battle. The threat of violence is constant and the shura at Char-e-Anjir was guarded by British troops from 1st Battalion Welsh Guards, who were involved in some of the heaviest of the recent fighting and lost seven members.

As well as the threat of violence – the Taliban has warned they will kill anyone who votes – the push for Pashtun votes also takes place amid feverish political manoeuvrings in Kabul.

More details are emerging of President Karzai's offer, first revealed in The Independent, of a cabinet seat for one of his rival candidates, the former finance minister and World Bank official Ashraf Ghani. The ploy is an attempt to undermine Mr Karzai's chief rival, Abdullah Abdullah.

A deal would help solidify the southern vote behind Mr Karzai – both he and Dr Ghani are Pashtuns – against Mr Abdullah, who is half Pashtun, but retains little power base in the community because of his long association with the Tajik- and Uzbek-dominated Northern Alliance.

Analysts say the deal has the support of the international community which would like a technocrat like Dr Ghani to bring his management experience to an increasingly wayward administration while keeping the Pashtun community, from where the Taliban draw their support, within the fold.

The British ambassador to Afghanistan, Mark Sedwill, who flew into Char-e-Anjir for the shura, denied that the international community had any intention of interfering in the election.

"What happens in this area will be extremely interesting because it is vitally important that the Pashtuns should come out and vote," he said.

"They make up 40 per cent of the population and of course they should have a say in the running of the country. This area has been brought back into the rule of the Government of Afghanistan, and we are slowly seeing normal life returning."

The Taliban's departure has already resulted in the town slowly resuming its economic life. Fazel Rahim, a 28-year-old shopkeeper, said: "We had fighting going on all the time and I could only open my store a few hours a day. But it's been more peaceful recently and I have a lot more customers. If things keep like this we will be happy. I am going to vote for the candidate who can maintain the peace, I have not decided who, but I'll vote."

But the scars of a traumatised society are only too evident. As the shura ends, Shah Mohammed, a 48-year-old farmer, flings away the election literature he has been handed.

"I will not vote for anybody. Our lives have been ruined. I cannot return to my farm because of the fighting and my crop has been destroyed. I blame everybody, the Government, the Taliban, the Americans, the British. What have they all brought us but misery?"

His nine-year-old son has an injured arm, the result of a blast. "I don't know who did it, the Taliban or are the foreign troops, but this is what we have to live with," he said.

Ahmed Jan, a carpenter, complains about security. "I have three children and they cannot go to school because the Taliban killed the headmaster. They say now that we are safe, but the school is still shut.

"What would happen is that the British would fight the Taliban, drive them away, and then go away themselves. The Taliban would come back and the fighting would begin again. The British are here now, and they should stay, we need security."

A voter's view: 'All I want is peace'

Wali Mohammed has experienced Afghan history in microcosm during his 71 years. His first job was with the Americans who invested heavily in Chah-e-Anjir to counterbalance Russian influence. Since then he has worked for four different masters.

"The Americans sent me to Iraq and Iran to teach me English. It is strange what happened later but at the time they were friends with these countries. We were sorry when they left because they spent a lot of money here and they treated us well.

"Then the Russians came [in 1979] and asked me to continue working here. They brought us tractors, they brought us food. But then there was fighting and they left as well.

"After that the Taliban came and burnt all the shops, but they asked me to stay and work and I did that. It was a difficult time but they left us alone and we just continued with the work of repairing what the Americans had built, but we had no spares and everything began to slip away in front of my eyes. Now we have the British and I am still working and I like it here, I wonder who else I will see in Afghanistan before I die," he says.

"I will probably vote for Karzai, there is no one else. I have had three sons killed in the violence, and that is very hard for a father. All I want is a chance for peace."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments