A search for justice by the women forced to marry strangers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

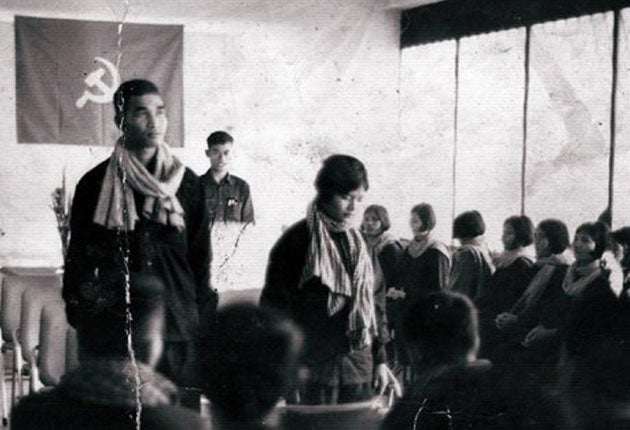

Your support makes all the difference.Pen Sokchan was just 16 when in late 1978 she was ordered to marry a Khmer Rouge soldier, a man who was a stranger to her. More than 30 years on, she remembers how she tried to prevent him consummating the marriage by wearing two pairs of trousers to bed.

"But my husband told the Khmer Rouge cadres about that, and they said if she refuses to have sex with you, tie her up with a rope," she says.

At that time Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge movement was in its final months of running Cambodia, and to disobey its word was to risk execution as a counter-revolutionary. Angkar, or the Organisation, the Orwellian name for the leaders, had decreed that people must marry in order to boost the population from 8 million to 20 million.

Across the country hundreds of thousands of men and women were married in small groups of perhaps a dozen people at a time.

At night Khmer Rouge cadres would stand underneath the stilted huts of each couple of newly-weds to ensure they consummated the marriage. Those that refused to do so would be "educated" to do their duty to the party. Those that still refused after three days, says Pen Sokchan, would be executed.

In Pen Sokchan's case her husband followed the cadres' suggestion, tying her up and raping her. Later that night her uncle helped her escape. Pen Sokchan, who lives in a village in rural Pursat province in western Cambodia, says her own family refused to let her stay at home.

"My mother said I had to leave because the Khmer Rouge cadres would kill us all if they found me there," she says. "So I spent nights at a friend's home and during the day I hid in the forest." Had she been found, she would have been killed for disobeying the Angkar, but this was late 1978 and Pol Pot's government would soon collapse, driven to the Thai border by an invading Vietnamese forces backed by Khmer Rouge defectors.

Pen Sokchan's story is told in a documentary called Red Wedding that premiered in Phnom Penh this month. Film-maker Chan Lida says 250,000 women suffered a similar fate to Pen Sokchan.

Even today Cambodia remains highly conservative when it comes to issues such as women's virginity and rape. Chan Lida, who is 31, says that is one reason her generation knows so little about the subject of forced marriage despite the fact that it was so widespread.

"All the women and men between 40 and 60 were forcibly married at least once by the Khmer Rouge regime," she says. "I wanted to know more about why this happened, and why [Pen Sokchan] had to suffer being forcibly married – it was not her fault."

Red Wedding traces Pen Sokchan's efforts to find out from the Khmer Rouge district leaders why she was selected for marriage. Despite those efforts, she fails to get the answers from those who held the power of life and death, and exercised it arbitrarily.

Forced marriage is one of numerous crimes ascribed to the movement, and along with genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, it is on the docket for the trial of the four surviving Khmer Rouge leaders whose trial at the UN-backed tribunal starts today.

Pen Sokchan is one of more than 600 men and women who have applied to be recognised as victims of forced marriage at the UN-backed tribunal.

Lawyer Silke Studzinsky, who represents 219 victims of forced marriage, says Pen Sokchan's story is very familiar. "The arrangements [are as] she described [in the documentary] – there were no ceremonies, no monks, nothing," she says. "They were married to somebody that they did not know before, and whom they did not like and did not love and did not want to be married to."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments