Three children, 19 years in the US, no criminal record: Meet the man still deported by Donald Trump

The family man cannot return to the US for at least 10 years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Donald Trump is splitting up families.

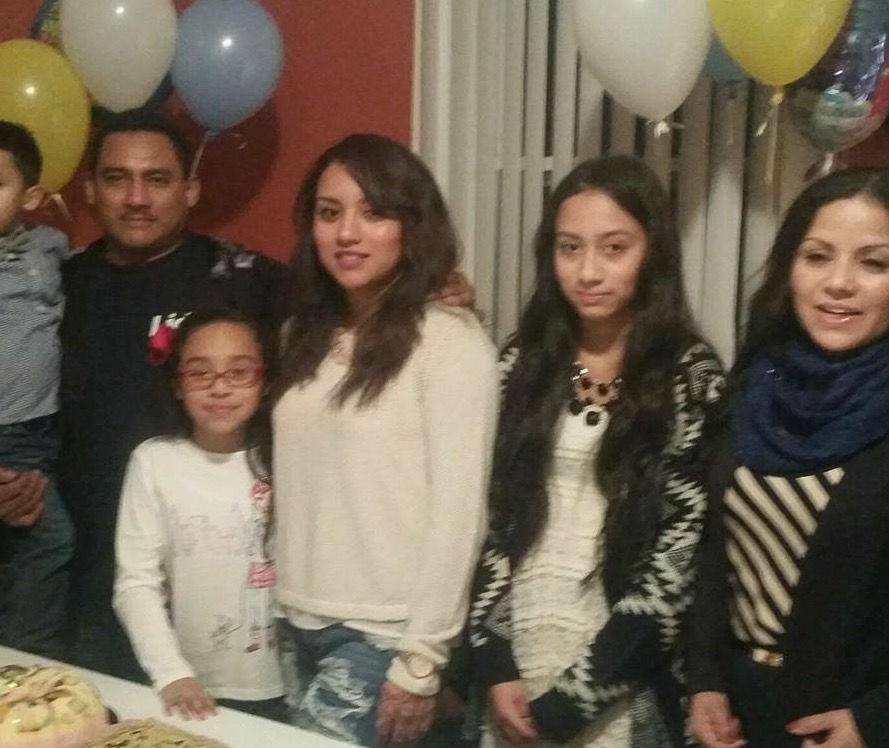

After 19 years living and working in the US, paying taxes and raising a family, Mario Hernandez Delacruz was deported to a country he had not seen for two decades.

His daughter, Estrella Garcia, and one of her younger sisters, drove him to the airport in the family’s Jeep Wrangler where he caught a flight to Mexico. On the way, they talked about their plan to carry on appealing his right to live in the US; on the way home, there were just tears.

“My mother has been so depressed. My two sisters – aged 15 and 12 – cannot concentrate at school. I’ve had to carry on because I’m now the head of the family,” says Ms Garcia, seated in the family’s modest home in south west Detroit. “I don’t think [Trump] cares. He just wants to get out people he doesn’t think belong here.”

As Mr Trump marks 100 days in the White House, the impact of his executive orders on immigration are reverberating across the country. Citizens from six Muslim-majority countries were told they could no longer enter the US, the nation’s refugee programme was suspended, and agents from US Customs and Border Protection have been raiding homes and business and deporting people deemed to be illegal.

Mr Trump had originally said his priority was deporting those undocumented migrants who had broken the law. But in Detroit and elsewhere, people who have lived in the country for decades and who have no criminal record are being detained and deported. Agents have been arresting people in courthouses and even as they leave church-operated cold weather shelters.

“My father had no criminal record. He worked, he volunteered in the community, and two of his children are US citizens,” says 23-year-old Ms Garcia. “Now, Dad is in Cancun with his mother and she is living in poverty. He calls every day and he says it's bad. He’s not allowed to apply to come here for 10 years… And neither my mother or myself can go there.”

Mr Delacruz, 44, entered the US illegally in 1998. He had grown up in Tabasco in southern Mexico. He crossed with wife, Matilde, and Ms Garcia, who was then aged just five. Her only memory of the journey is of being carried by her father and another man.

In Michigan, Mr Delacruz worked as a carpenter and flooring specialist. He had two other daughters, Lucero and Diana, and was a member of the United Hispanic Pentecostal Church, located a couple of streets from their home. He also volunteered with a local organisation, Michigan United, which works to help poor families, many of them immigrants.

The group’s executive director, Ryan Bates, says the issuance of the President’s executive orders was a moment when people in the community came together to fight in a way that was unprecedented.

There were protests and rallies involving various faiths and communities. One event involved a march from a Latino Catholic church to a neighbourhood mosque.

“What is at stake is not just immigration policy, but the vision for our country. Are we going to be a place where everyone has an equal political voice?” asks Mr Bates.

“Because, for more than 200 years, we’ve not been that. It took generations of struggle to bring in people. But Trump wants to turn back the clock to a time when only people who looked like me were full citizens.”

Cindy Garcia’s husband, Jorge, is also in a perilous situation. He came to the US in 1989 when he was aged just nine or ten. His parents are still in the country illegally, while Mr Garcia lives in a legal grey zone, permitted to remain by the authorities for now, but at risk of deportation.

“We’re very frightened because we fear he could be taken at any time,” says Mrs Garcia, a US citizen. She says that since Mr Trump’s executive orders, people are feeling more vulnerable, even though her husband’s legal battle dates back more than a decade.

She says they have two children, a 14-year-old daughter, Soleil, and 11-year-old Jorge Jr, who are also US citizens. She says her husband works and pays taxes. She cannot understand why the authorities would want to threaten him.

Mr Garcia says that if he were to return to Mexico, he would struggle. “It would be like going to a country I don’t know because things have changed,” he says. “I’ve not been back since I came here.”

Mr Trump made a crackdown on undocumented migrants a major part of his election campaign and has vowed to build a wall along the Mexican border. While his executive orders relating to a travel ban have been put on hold by the courts, two other orders – one that tightens border security and another focused on enforcement inside the US – are impacting on communities.

During his address to the joint houses of Congress in February, Mr Trump announced: “As we speak, we are removing gang members, drug dealers, and criminals that threaten our communities and prey on our citizens. Bad ones are going out as I speak tonight and as I have promised.”

But as The Intercept pointed out, Mr Trump’s immigration crackdown – a toughening of a stance that activists said was already draconian under Barack Obama – sets as high a priority for people who have “abused any programme related to receipt of public benefits” as it does for convicted offenders or people who had committed violence.

“The Trump administration has launched an unprecedented attack on the American idea that we should welcome immigrants and refugees, and build a stronger country in the process,” Frank Sharry, executive director of the pro-immigrant America’s Voice Education Fund, told reporters earlier this year.

“They are using the cover story of ‘bad hombres’ as a smokescreen for a strategy that declares open season on each and every undocumented immigrant in America.”

In a statement, US Customs and Border Protection, said: “Mario Hernandez-Delacruz, an unlawfully present citizen of Mexico, was ordered removed from the United States after failing to voluntarily depart as ordered by a federal immigration judge in 2012.

“In an exercise of discretion and prior to his departure, Enforcement and Removal Operations (ICE) had allowed Mr Hernandez-Delacruz to remain free from custody with periodic in-person reporting.”

Ms Garcia’s presence in the US depends on the protection offered to children arriving in the country by DACA, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals programme.

While her two younger sisters are US citizens and can travel freely, she and her mother are unable to leave with any guarantee of being able to re-enter the country. As a result, they are unable to visit their father.

She says Mr Delacruz ultimately had five weeks from being told he had to leave, to the journey to Detroit Metropolitan Airport. She tried to spend as much time with him as possible, but he was always busy. His wife cooked him his favourite meals.

Now he is in Cancun, she says her father appeared shocked by the poverty his mother was living in there.

“The immigration officer said he was sorry what was happening but he had a daughter,” says Ms Garcia. “But I was so angry. I wanted to say ‘You don’t know what it’s like because this is not happening to you’.”

Speaking in a mixture of halting English and Spanish, from his new home in Mexico, Mr Delacruz says the situation is “very sad”. “The situation is bad because I’m here and my family is in Michigan,” he says.

He explains he is obliged to stay in Mexico for ten years before he can apply to return to the US. Is there nothing he can do to change the situation? He replies in the negative. “Nada…Nada.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments