Divisions over Donald Trump inspiring rift among US evangelical Christians

Having secured votes from 81% of white evangelicals during the election, President's subsequent performance and policies have proven less popular with churchgoers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The 2016 presidential contest highlighted just how deeply divided the United States is over both politics and religion. The vast majority of white evangelicals (81 percent) voted for Trump. A strong majority of religious “nones” — those who do not identify with any religious tradition — voted for Clinton (68 percent).

Of course, the divide does not stop at the vote. For example, between May 2016 and February 2017, almost every religious group came to oppose Trump’s proposed temporary ban on allowing Muslims into the US. The exception? White evangelical Protestants, who increased their level of support for the policy. The largest gap on this issue is the one between evangelicals and nones, which grew from 28 to 41 percentage points.

How did we get here? One answer is sorting. That is, people may reevaluate their religious membership when they sense political (or other) disagreement, leaving their houses of worship more homogeneous organisations. While this happens across the religious spectrum, here we highlight new evidence that disagreement over Trump’s candidacy actually led some evangelicals to leave their church.

We surveyed 957 people before and after the 2016 presidential election, in late September and mid-November. Our goal was to gather data to assess how politics might shape church membership. While technically a convenience sample, our surveys — which were fielded online — are broadly representative of the American public.

Of those who said they had attended a house of worship in September, 14 percent reported that they had left that particular church by mid-November. That’s a proportion in line with several of our previous estimates from surveys in the 2000s. In the 2016 election, “leavers” were distributed across the religious population, and included 10 percent of evangelicals, 18 percent of mainline Protestants, and 11 percent of Catholics. This represents an enormous amount of churn in the religious economy.

But was that churn influenced by politics? To find out if they attended a “political church,” we asked respondents if their clergy addressed any of eight political topics. We also asked, more generally, if seeing evidence of politics reminded them of how divisive politics has become. About 15 percent of those who believe that American politics has become divisive left their political houses of worship. Of those who don’t think politics is inherently divisive, close to none left their political house of worship.

For some, any mention of politics seems divisive, and they wish to leave it behind at worship. Others don’t mind some mention of politics, but are disturbed by mention of particular political disagreements. Arguably, Trump has been the most divisive candidate in at least recent US history. So was conflicting sentiment about Trump more likely to drive some out of their houses of worship? We wondered this in particular about evangelical Protestants, among whom the question of Trump was hotly debated; some supported him while others were prominently #NeverTrump-ers.

In the same survey, we asked evangelicals first to tell us their own level of support for Trump, and second to estimate their clergyperson’s support of Trump. Among this group, Trump’s average feeling thermometer rating — which ranges from 0 to 100 — was just over 48. While that’s low, Hillary Clinton’s average was only 25. On average, they felt their clergy liked him only slightly better, averaging 50 on the same 100-point scale.

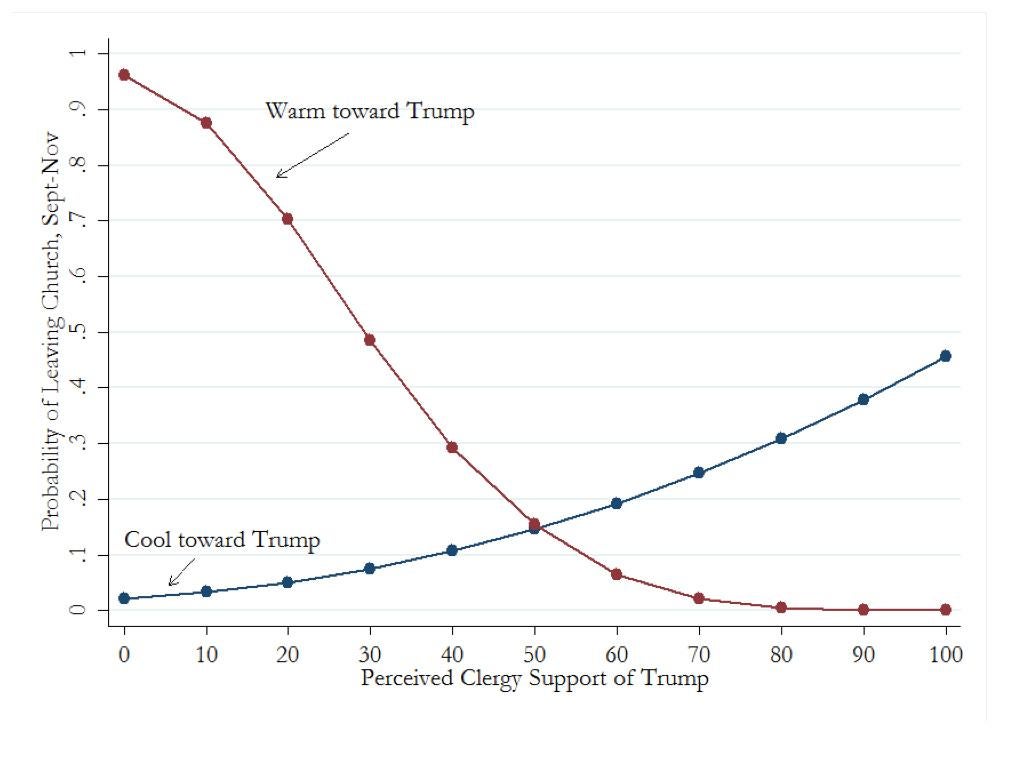

In the figure below, which shows results from a regression model, you can see that those who felt that they and their clergy disagreed over Trump in September were the most likely to report leaving that house of worship by November.

The two groups you’d expect were more likely to leave: Trump supporters who felt their clergy didn’t support him (represented by the red line on the left), and those who felt cool toward Trump but thought their clergy strongly supported him (represented by the blue line on the right).

This finding might help explain why evangelical clergy appear to have had little to say about Trump in their churches this fall. It’s very likely that they were concerned about alienating some of their flock.

These dynamics are not unique to 2016, or to Trump. In our forthcoming article in the American Journal of Political Science, we show similar evidence from our two decades of data gathering: Marginal attenders leave churches when they sense political disagreement.

More specifically, for 20 years, liberal to moderate evangelicals have been leaving their churches because they disagree with the Christian right. This is important because it allows us to recognise that this sorting process is plural, local, and continual. It is not something owned by the left or right, but a regular and expected part of life in all religious organisations.

Are these patterns troubling? Observers’ opinions differ. Religious institutions have long been practice grounds for skills later turned toward politics. On the one hand, if people are leaving houses of worship because of political disagreements, they may not be learning the skills needed to talk across differences and participate in politics.

On the other hand, as congregations become more engaged with politics, worshipers learn to connect their values with their political options. And the members most likely to leave over political disagreements tend to be marginal, infrequent attendees anyway.

People leaving their houses of worship over political disagreements is natural and to be expected. It’s certainly happened frequently, sometimes explosively, over the history of religion.

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments