The great combover: Would we have elected Trump if he was bald?

America has been voting for a head of state but what it got was a head of hair. Andy Martin deconstructs the presidential hairdo and discovers you can see right through it. His hair doesn’t care about truth, it’s all about form and style, an airy helmet doomed to collapse

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At his inauguration, in 1804 in Notre Dame, Napoleon Bonaparte placed the imperial crown on his own head with the pope and all the assembled glitterati of the period looking on. Donald Trump’s coiffure is, in effect, a crown that he has placed on his head, a soufflé of hair, a gorgeous, shimmering, airy helmet, an unstable architecture that is doomed to collapse. It’s myth and miracle, a form of levitation applied to hair, it’s like seeing hair walking on water.

Call it vanity, if you will, call it narcissism, call it a heroic King Canute-like struggle against the tide of time. But what you can’t say is that it’s incidental. The hair is not an add-on, a mere supplement. The Trump haircut is a construct and displays the essence of the man and a grand tradition of American politics.

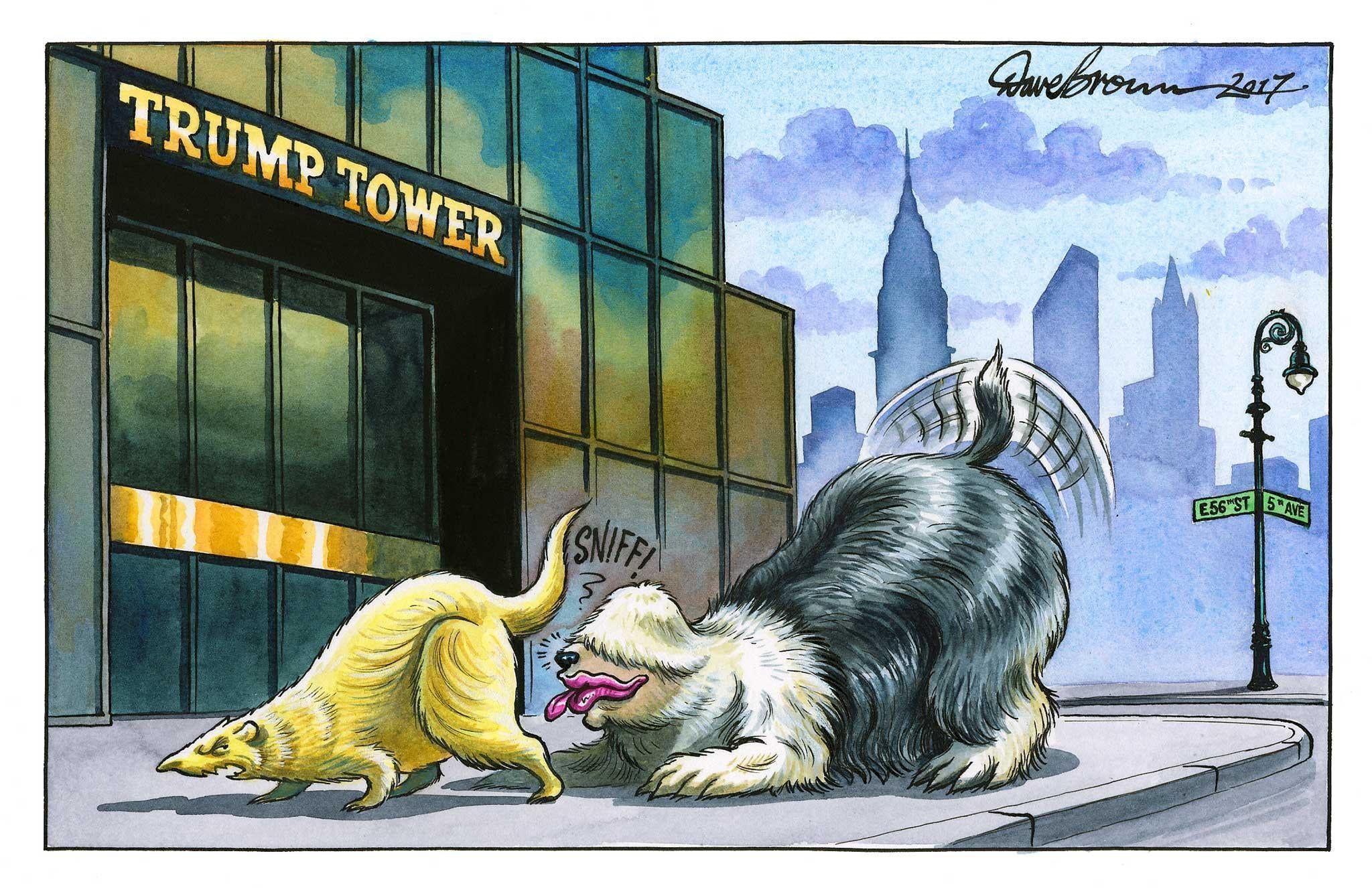

It’s a microcosm of Trump Tower and, as the great cultural critic Roland Barthes said of the Eiffel Tower, it contains nothing, you can see right through it, and yet it remains “an empty sign that means everything”.

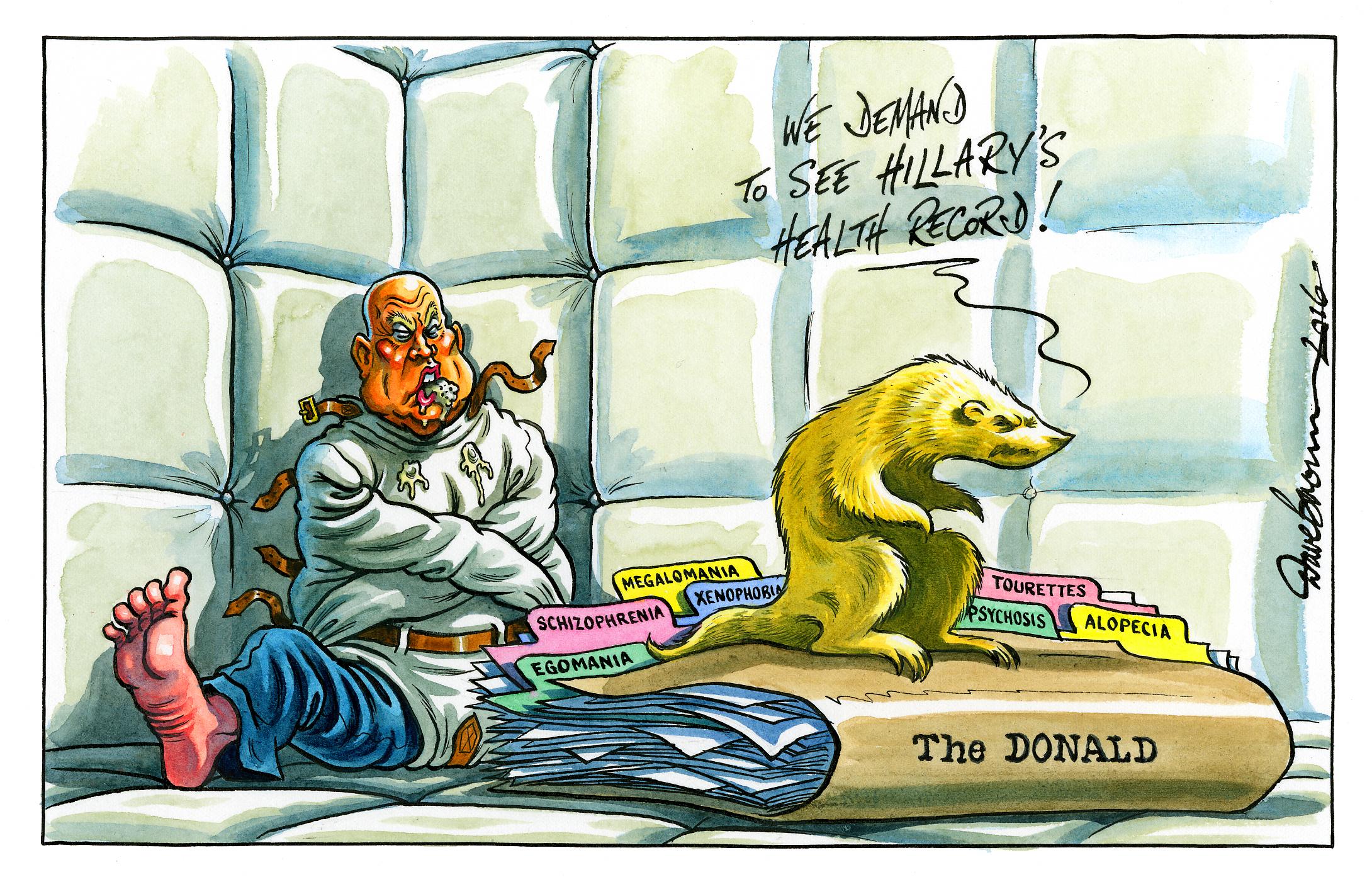

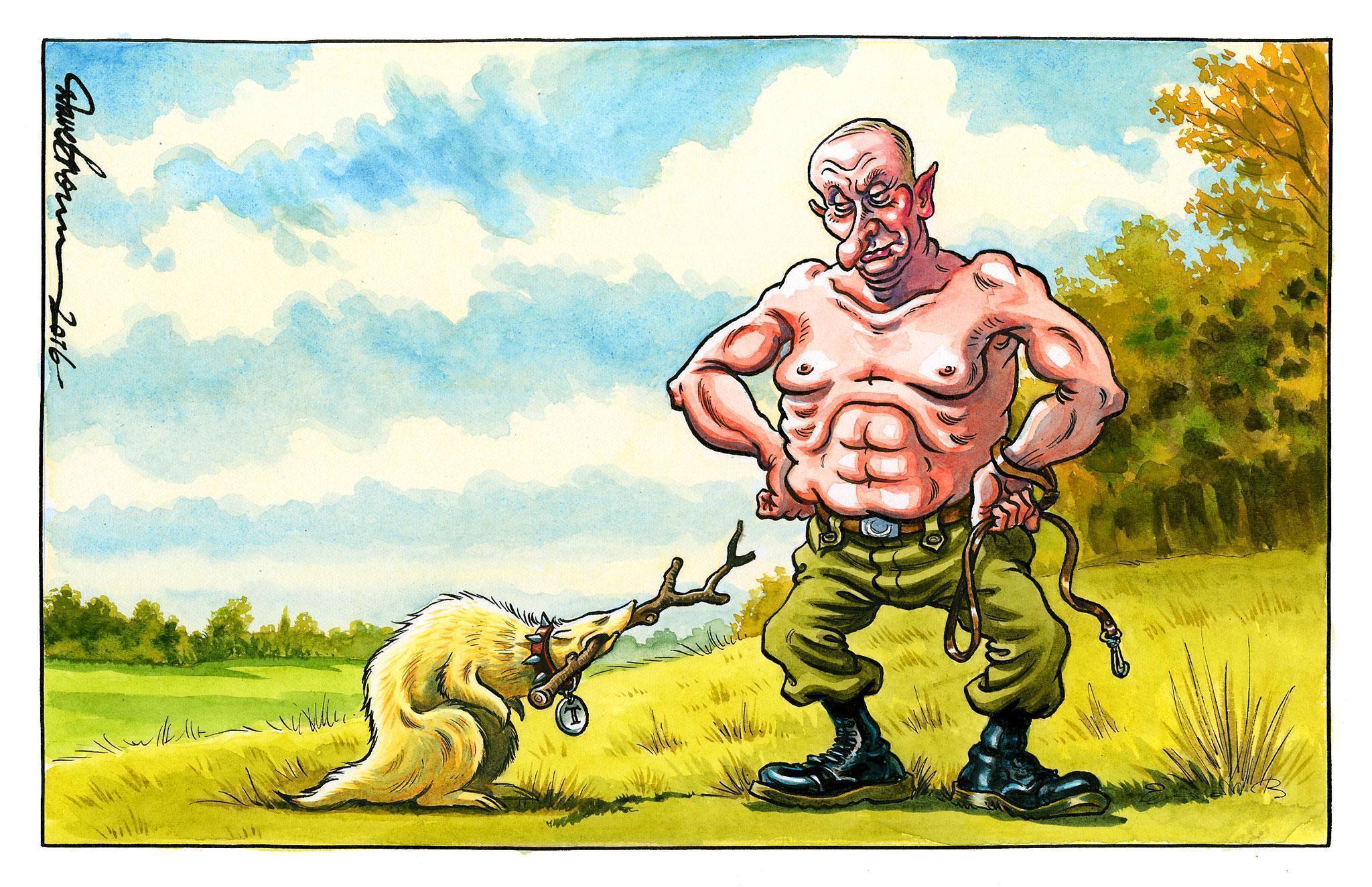

Trump’s hair is a whole follicular philosophy all on its own – or phallicular, more accurately, given the strutting, jutting, preening coxcomb of groping sexuality it implies. Imagine a head more like Bruce Willis. Or Patrick Stewart. It would imply a radically different slant. Would an alopecic Trump have even been elected? I doubt it. America has been voting not for a head of state but a head of hair. Oblige everyone to wear a decent hat, as per Mad Men or High Noon, and the Democrats would have won.

The President’s hair is as scripted and choreographed as a WWE wrestling match. It’s the opposite of natural. Everything about it is carefully staged and micro-managed.

Perhaps the massive combover, as if licked into place by a passing angel, has the allure of a new evangelical religion, with its own built-in anthem, “We Shall Overcomb”. Experts have been appointed and have conducted experiments to determine whether the phenomenon is real or not. But they are wasting their time. The hair is post-truth, but unlike global warming, it is not a Chinese hoax. Buried within those lacquered swirls and curls is an intellectual history that deserves to be better known.

The semiotics of the Trump tresses were recently brought into focus by the furore around a single paragraph written by the late American philosopher Richard Rorty, in Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America. Rorty, with some degree of prescience at the end of the last century, predicted that “the non-suburban electorate will decide that the system has failed and start looking around for a strongman to vote for – someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and postmodernist professors will no longer be calling the shots.”

It’s a tempting theory. Fascism will return: Mussolini, Hitler… Trump. Even President Obama seems to have concurred. It’s adjacent to the argument set out by Jean Baudrillard, the “pope” of post-modernism, who said that America divides into two: there are the coasts where everyone is slim and drives small cars, and the bit in the middle where everyone is fat and drives big cars. Surprisingly, whenever I put this theory to anyone on the East or West coast, they think about it for a second, then nod and say, “Yes, that’s right.” I have only mentioned it once to a guy in Montana, who owns a dozen different guns and shoots and eats bear for breakfast (literally), and he said not to mention it to any of his fat neighbours. Hip on the coasts (anti-Trump), hick (pro-Trump) in the middle: it’s a map of America that has become popular post-election, almost a cliché.

Rorty was brilliant at theorising. I remember him coming over to England a few years back and driving everyone crazy because he didn’t agree with anyone about anything and was imperturbable except when he discovered anyone agreeing with him. His great early work was Philosophy and The Mirror of Nature, in which he argued that “holding up the mirror to nature” (as Hamlet recommended) or “carrying a mirror along the highway” (Stendhal) was a vain enterprise. Truth, as Nietzsche put it, was an illusion about which we have forgotten that it is an illusion. All that was left was irony or “pragmatism”. Which, in a more political phase, Rorty hitched up to “leftist thought” and postmodernist professors. Democrats were ironists while Republicans were nostalgic literalists. I am sure Rorty would have been very relieved to know that I disagree.

The presidential hairstyle shows that this narrative is wrong. Clearly the hair is not hip, but neither is it hick. The hair is an ironic exercise in postmodern self-referentiality. If we want to understand anything about the success of Trump we need to forget about hipsters and hicks and everything we thought we knew about Democrats and Republicans. And about nineteenth-century America. You think it was all Shane and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly? Think again. From Plato’s Academy through to the Parisian café, we have always associated freewheeling philosophical speculation with Europe, and America, in contrast, with hardcore empiricism and gunslingers.

Even Americans think like this. Consider Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris: all the smart American writers have to go to Paris for inspiration. But ideas are perfectly capable of migrating in the other direction or just springing up unbidden – yes, even in America. Rorty used to hark back to John Dewey (1859-1952) as his main source and inspiration for “pragmatism”. Louis Menand, in The Metaphysical Club takes us on a magical mystery tour around such post-Civil War thinkers as William James (The Varieties of Religious Experience) and Charles Sanders Peirce, who is seen by Umberto Eco as the founder of semiotics, in which there is always a massive preponderance of unanchored signs, symbols and “icons” over any cold, hard, objective correlative.

The 19th century in the US was the golden age of the utopia and of transcendentalism, long before the Beatles and the Maharishi. The late 20th century saw the infusion, into this heady mix, of European post-structuralism and deconstruction, which – like Richard Rorty – seeks to overthrow realism, to heap scorn on A J Ayer’s holy trinity of language, truth, and logic (mere “logocentrism” to Derrida’s way of thinking). Rather like Trump’s hair, everything tends to become an “aporia” (a confusing tangle of thought, or insoluble puzzle).

If we are to make any sense of the current intellectual drama being played out in the US, beyond mere hoopla, we need to resort to Ludwig Wittgenstein, an Austrian who became a student and then colleague of Bertrand Russell at Cambridge. In his first major work, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, he argues that “the world is everything that is the case” and that the point of language is to provide a “picture” that mirrors, perhaps in its very grammar, the structure of the world. He was inspired by discovering a car magazine in the trenches of the First World War, in which the different parts of the car had arrows pointing to them and names attached – “ostensive definition”.

This, he thought, was the main function of language. This is how we learn new languages, after all, and what we exist to do – as in the Garden of Eden – to give names to all the animals and plants (and cars etc). But in his later Philosophical Investigations Wittgenstein backs away from this clear, if perhaps naive, perspective and proposes instead his theory of “language games”. Games have to be taken seriously because there is nothing but games, governed by different sorts of rules. Only one of them is the habit of mimesis, as captured in the picture theory of the Tractatus. Others include songs, prayers, exclamations, hypotheses, commands, play-acting, and philosophy itself, which is a form of tautology. And you might add, presidential tweets.

Donald Trump is, like Richard Rorty, indifferent to the mirror of nature. He doesn’t see himself labelling the parts of the car at all. He is playing a very different kind of game. He has adopted the philosophy of pragmatism in its most extreme form, according to which language has only an ironic relation to truth but exists fundamentally to persuade people to do things. To cast a vote, for example, in someone’s favour. So it is that when I read yet another article in the New York Times accusing Trump (at some level quite correctly) of another falsehood, it strikes me that they really need to consult the Philosophical Investigations, because Trump is playing another kind of game entirely. Perhaps, as Wittgenstein suggests, “play-acting”.

Journalists are judging him by a set of rules which he does not even acknowledge. This stark division was neatly summed up for me the other day in an article in The New Statesman by Helen Lewis who, in her rejection of Trump, argued that “any discussion of politics relies on basic agreed facts, from which flow a common reality”. There is no common reality in the world of Trump, nor facts. Trump’s intellectual development was inflected by American pragmatism and European postmodernism, but mainly, at their confluence, by his studies at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in “Real Estate”, which should more properly be known as “Hyperreal Estate”. Or just plain “Unreal”.

No one in real estate feels constrained by the demands of mirror theory or mimesis. Whatever is in bad nick has “potential”. And what is in really bad nick has “great potential”. If it’s falling down it’s “picturesque”. As Charles Sanders Peirce neatly explained, language here is only a “stimulus pattern”. The laments of the New York Times and the New Statesman remind me of the argument between Jules Verne and HG Wells regarding their different versions of how to get to the moon. Verne used a rocket, Wells preferred gravity-defying paint. “Mais il invente! ” Verne objected. “He makes shit up! ” to give a rough, contemporary translation. So too the new President. He is playing a non-mimetic game, in which the point of language is not to describe or report anything but to be a “performative”, like the inauguration itself, designed quite simply to make him into a President. His hair doesn’t care about truth, it’s all about form and style and semiotics. What, as Peirce asked, if “the facts” were given “a certain swerving?” And what if they were also given a blow-dry, colouring, and a tubful of gel?

Hillary Clinton and the Democratic party generally are still, like Helen Lewis, deeply attached to a mirror theory of language and the concept of a “common reality”. They need to get over it and start playing some different language games. It is obvious that Trump won the election thanks to his shrewd exploitation of two extremely successful and paranoid genres, the western and noir (crime fiction/thriller). Trump has passed himself off as a sheriff (or action hero) riding into town (in this case Washington) to get rid of all the bad guys. As a friend said to me, “But that’s the best narrative there is, so Trump has won, we might as well give up!”

Certainly, for Democrats and Trumpophobes across the world to confine themselves to saying, as of a pantomime villain, “Oh no he isn’t! ” won’t quite cut it. They need another genre. I recommend science fiction. I think Keanu Reeves should run the next time around as ''the One” who, as in The Matrix, can save us from the evil giant insects who are sucking the life out of humankind and turning reality into “the desert of the real”.

Just so long as he has a decent head of hair.

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’ (Bantam Press, RRP £18.99). He teaches at Cambridge University. Follow him @andymartinink

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments