Road fatalities in Colorado have plummeted since marijuana was legalised

Since Colorado changed its laws, 'drugged driver' panic has only intensified

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Since Colorado voters legalised pot in 2012, prohibition supporters have warned that recreational marijuana will lead to a scourge of “drugged divers” on the state’s roads. They often point out that when the state legalized medical marijuana in 2001, there was a surge in drivers found to have smoked pot. They also point to studies showing that in other states that have legalized pot for medical purposes, we’ve seen an increase in the number of drivers testing positive for the drug who were involved in fatal car accidents. The anti-pot group SAM recently pointed out that even before the first legal pot store opened in Washington state, the number of drivers in that state testing positive for pot jumped by a third.

The problem with these criticisms is that we can test only for the presence of marijuana metabolites, not for inebriation. Metabolites can linger in the body for days after the drug’s effects wear off — sometimes even for weeks. Because we all metabolize drugs differently (and at different times and under different conditions), all that a positive test tells us is that the driver has smoked pot at some point in the past few days or weeks.

It makes sense that loosening restrictions on pot would result in a higher percentage of drivers involved in fatal traffic accidents having smoked the drug at some point over the past few days or weeks. You’d also expect to find that a higher percentage of churchgoers, good Samaritans and soup kitchen volunteers would have pot in their system. You’d expect a similar result among any large sampling of people. This doesn’t necessarily mean that marijuana caused or was even a contributing factor to accidents, traffic violations or fatalities.

This isn’t an argument that pot wasn’t a factor in at least some of those accidents, either. But that’s precisely the point. A post-accident test for marijuana metabolites doesn’t tell us much at all about whether pot contributed to the accident.

Since the new Colorado law took effect in January, the “drugged driver” panic has only intensified. I’ve already written about one dubious example, in which the Colorado Highway Patrol and some local and national media perpetuated a story that a driver was high on pot when he slammed into a couple of police cars parked on an interstate exit ramp. While the driver did have some pot in his system, his blood-alcohol level was off the charts and was far more likely the cause of the accident. In my colleague Marc Fisher’s recent dispatch from Colorado, law enforcement officials there and in bordering states warned that they’re seeing more drugged drivers. Congress recently held hearings on the matter, complete with dire predictions such as “We are going to have a lot more people stoned on the highway and there will be consequences,” from Rep. John Mica (R-Fla.). Some have called for a zero tolerance policy — if you’re driving with any trace of pot in your system, you’re guilty of a DWI. That would effectively ban anyone who smokes pot from driving for up to a couple of weeks after their last joint, including people who legitimately use the drug for medical reasons.

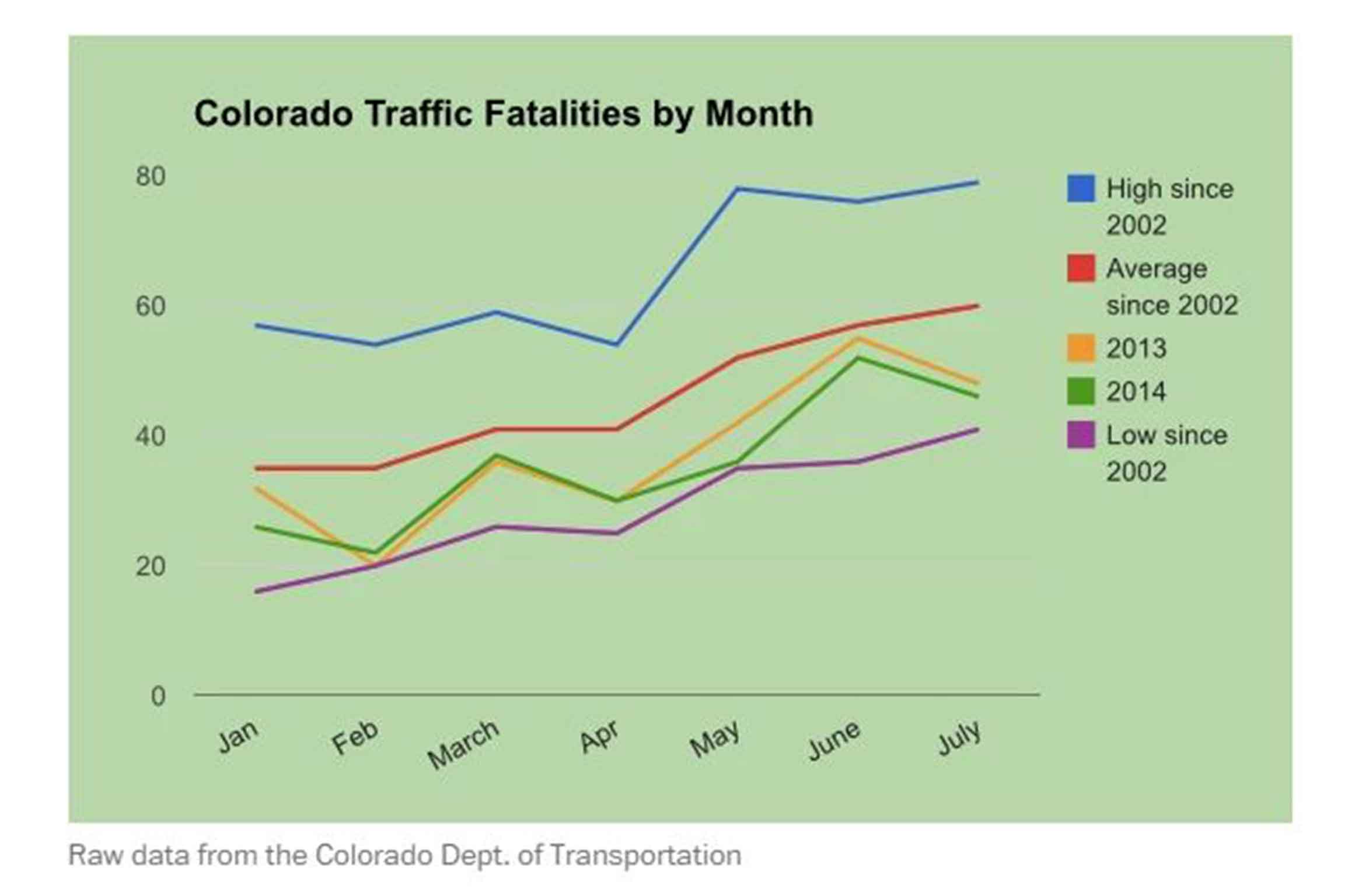

It seems to me that the best way to gauge the effect legalisation has had on the roadways is to look at what has happened on the roads since legalisation took effect. Here’s a month-by-month comparison of highway fatalities in Colorado through the first seven months of this year and last year. For a more thorough comparison, I’ve also included the highest fatality figures for each month since 2002, the lowest for each month since 2002 and the average for each month since 2002.

As you can see, roadway fatalities this year are down from last year, and down from the 13-year average. Of the seven months so far this year, five months saw a lower fatality figure this year than last, two months saw a slightly higher figure this year, and in one month the two figures were equal. If we add up the total fatalities from January through July, it looks like this:

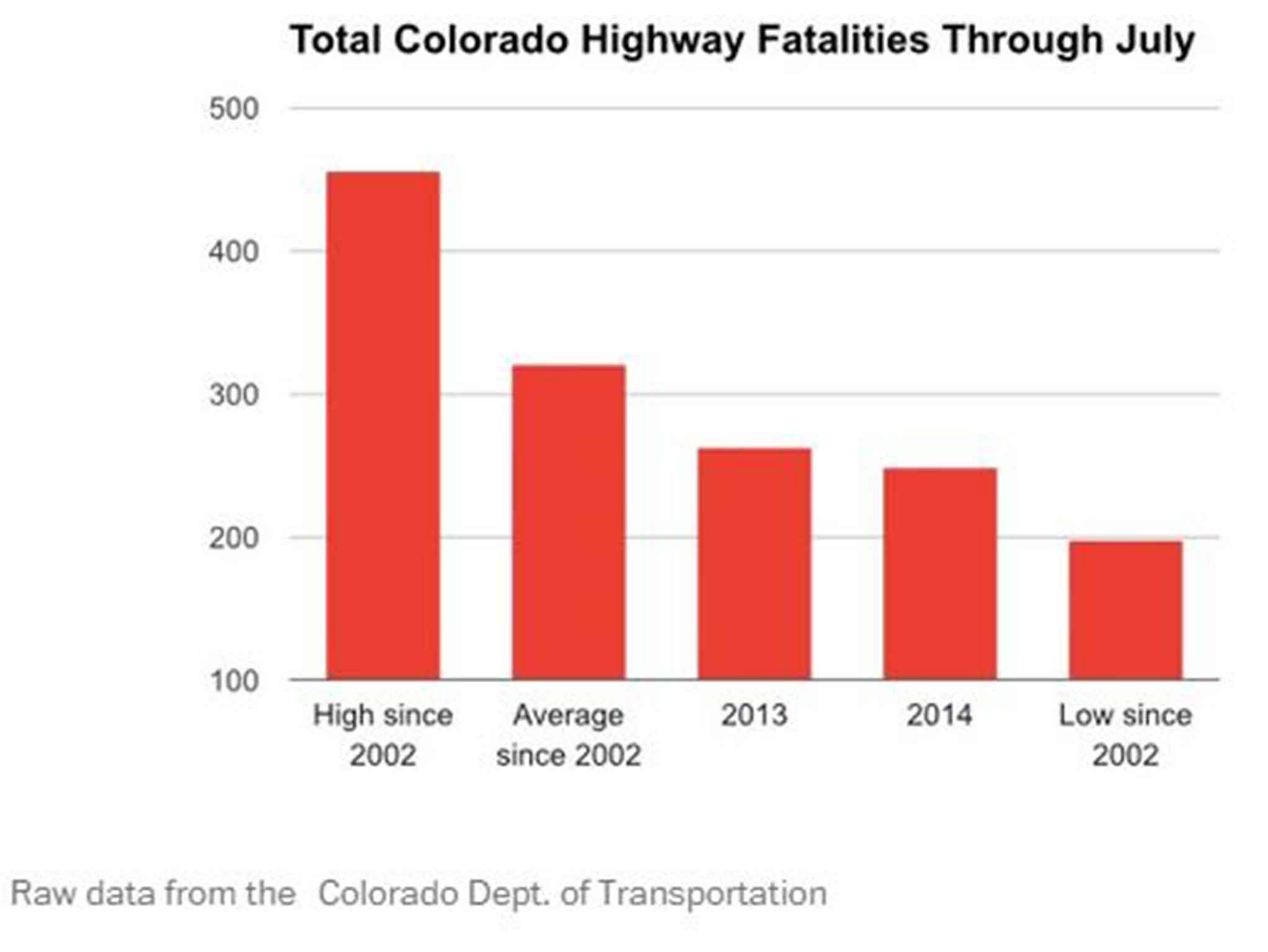

Here, the “high” bar (pardon the pun) is what you get when you add the worst January since 2002 to the worst February, to the worst March, and so on. The “low” bar is the sum total of the safest January, February, etc., since 2002. What’s notable here is that the totals so far in 2014 are closer to the safest composite year since 2002 than to the average year since 2002. I should also add here that these are total fatalities. If we were to calculate these figures as a rate — say, miles driven per fatality — the drop would be starker, both for this year and since Colorado legalised medical marijuana in 2001. While the number of miles Americans drive annually has leveled off nationally since the mid-2000s, the number of total miles traveled continues to go up in Colorado. If we were to measure by rate, then, the state would be at lows unseen in decades.

The figures are similar in states that have legalised medical marijuana. While some studies have shown that the number of drivers involved in fatal collisions who test positive for marijuana has steadily increased as pot has become more available, other studies have shown that overall traffic fatalities in those states have dropped. Again, because the pot tests only measure for recent pot use, not inebriation, there’s nothing inconsistent about those results.

Of course, the continuing drop in roadway fatalities, in Colorado and elsewhere, is due to a variety of factors, such as better-built cars and trucks, improved safety features and better road engineering. These figures in and of themselves only indicate that the roads are getting safer; they don’t suggest that pot had anything to do with it. We’re also only seven months in. Maybe these figures will change. Finally, it’s also possible that if it weren’t for legal pot, the 2014 figures would be even lower. There’s no real way to know that. We can only look at the data available. But you can bet that if fatalities were up this year, prohibition supporters would be blaming it on legal marijuana. (Interestingly, though road fatalities have generally been falling in Colorado for a long time, 2013 actually saw a slight increase from 2012. So fatalities are down the year after legalisation, after having gone up the year before.)

That said, some researchers have gone so far as to suggest that better access to pot is making the roads safer, at least marginally. The theory is that people are substituting pot for alcohol, and pot causes less driver impairment than booze. I’d need to see more studies before I’d be ready to endorse that theory. For example, there’s also some research contradicting the theory that drinkers are ready to substitute pot for alcohol.

But the data are far more supportive of that than of the claims that stoned drivers are menacing Colorado’s roadways.

CLARIFICATION: I wrote that “we can test only for the presence of marijuana metabolites, not for inebriation.” That isn’t quite accurate. This is true of roadside tests. But a blood test taken at a hospitals can measure for THC, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana. That said, even here there are problems. Regular users can have still have remnant THC in their blood well after the effects have worn off. Regular users can also have levels above the legal limit and still drive perfectly well. In Colorado, a THC level of 5 nano grams or more brings a presumptive charge of driving under the influence. However, references to “marijuana-related” accidents in studies, by prohibitionists, and by law enforcement could refer to any measure or trace of the drug. So when officials and legalisation opponents talk about increases in these figures, it still isn’t clear what any of this means for road safety.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments