The mystery of the missing Amazonian rubber slaves

Two men brought to the UK to highlight their tribe's fate never made it back home

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

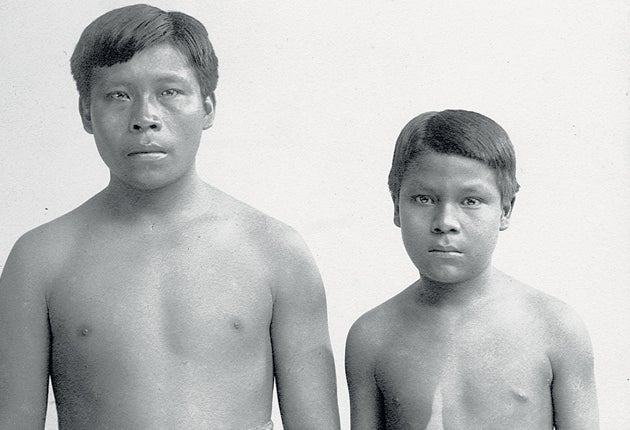

Your support makes all the difference.Omarino was exchanged for a pair of trousers and a shirt. Ricudo was won in a game of cards.

The British public first met the embattled gazes of the two men 100 years ago when their faces appeared in the pages of the Daily News. The British consul Roger Casement had brought them to Britain from their homes in the Colombian Amazon to highlight the fate of their people.

In the United States, Henry Ford's Model T cars, with their revolutionary vulcanised rubber tyres, were flying off production lines. Thousands of miles to the south, the tribes of the Amazon rainforest were being enslaved, tortured and murdered in the thousands to feed the boom in the rubber that grows on trees there.

Now, Fany Kuiro, from the same Witoto Indian tribe as Omarino and Ricudo, has appealed to the world to find out what happened to her two "indigenous brothers... so that our ancestors' spirits can rest in peace".

Mr Casement, an Irishman, had been working as the British consul in Rio de Janeiro when he was sent by the British government to investigate atrocities in the Amazon at the hands of the Peruvian Amazon Company and its British directors. "Alas! Poor Peruvian, poor South American Indian!" he wrote in his diary. "The world thinks the slave trade was killed a century ago! The worst form of slave trade and slavery – worse in many of its aspects, as I shall show – than anything African savagery gave birth to, has been in full swing here for 300 years.

"The dwindling remnant of a population once numbering millions is now perishing at the doors of an English company, under the lash, the chains, the bullet, the machete to give its shareholders a dividend."

Mr Casement wrote in great detail of the horrific treatment of the Amazonian Indians, estimating that at least 30,000 people in the Putumayo region of Southern Colombia had been tortured, murdered or forced into slavery.

"We are sent far, far into the forest to get rubber, and if we do not get it, or if we do not get it quickly enough, we are shot," Omarino told the Daily News, a popular national newspaper founded and edited by Charles Dickens. "London is very wonderful, but the great river and the forest, where the birds fly, is more beautiful. One day we shall go back."

The men did make it back to South America in the end, but the last known record of their whereabouts shows them separated from their homes by thousands of miles of thick rainforest.

Mr Casement's papers show that he handed them to the family of George Babbington Mitchell, the British consul in Iquitos, the largest city on the Peruvian Amazon.

Mr Mitchell wrote to Mr Casement in March to tell him that Omarino had taken a job on a ship heading north towards Colombia. Ricudo managed to find his wife, but Mr Casement never learnt the couple's whereabouts.

Many of the Amazon's uncontacted tribes that so fascinate social anthropologists are thought to be descendants of survivors of the rubber-boom atrocities, who fled to remote areas of the forest to escape the killings, torture and disease that decimated the indigenous population.

In some areas, 90 per cent of the Indian population was wiped out. But it was not the actions of Mr Casement and other campaigners that brought an end to the enslavement of the tribespeople. The Amazon rubber boom ended because more profitable plantations were established in South-east Asia from seeds smuggled out of Brazil by the British "bio-pirate" Henry Wickham. As for Mr Casement, he was knighted in 1911 in recognition of his efforts on behalf of the oppressed people of the Amazon and the Congo, where he did similar work.

But his experiences there made him a strident anti-imperialist and ultimately an Irish republican. In 1916 he was arrested and tried for treason in the wake of the 1916 Easter Uprising. During the trial, a second and less lofty diary appeared in the popular press, which purportedly revealed him to have been a promiscuous sex tourist with a fondness for young men.

As W B Yeats's poem "The Ghost of Roger Casement" recounts, he was hanged within three months.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments