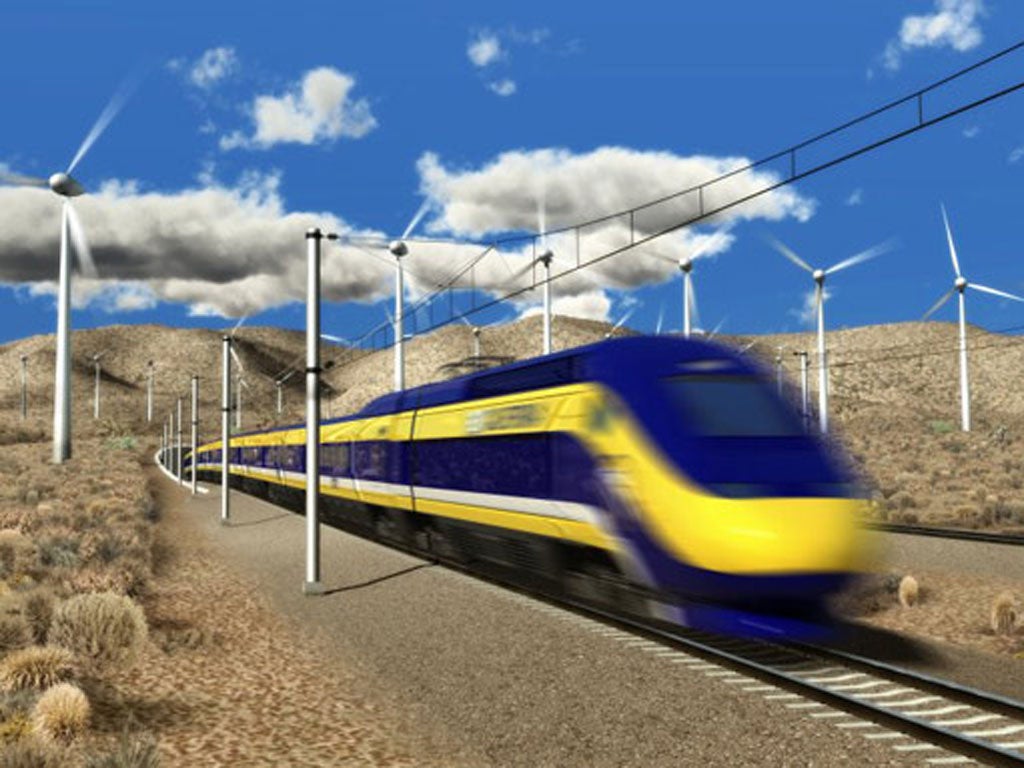

The bullet train to nowhere: California's rail nightmare

It was billed as a futuristic solution to a gigantic state's transport problems - but now it is seen as a white elephant. Guy Adams reports on a $68bn PR disaster

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With its vast pool, leafy trees and spotless lawn, the garden of Jeff Taylor's family home feels like a corner of Eden. "If you turn on the water and shut your eyes," he says, pointing to an array of artificial streams and waterfalls, "it sounds like you're up the road in Yosemite."

But not for long. Clutching a slab of A4 paper, Mr Taylor, a professional landscape architect, waves at the horizon. "I spent almost 10 years building this place, with my own hands," he says. "It's my home. It's irreplaceable. And all of it, every last bit, is about to be destroyed."

Mr Taylor has the great misfortune to have created his suburban dream in a residential neighbourhood of Bakersfield, a medium-sized city in California's Central Valley, which has been chosen as the starting point for one of the most ambitious - and controversial - engineering projects in America's recent history.

In the next 12 months, ground is due to be broken on a project to link California's major cities with an eco-friendly, state-of-the-art high-speed rail network, similar to Japan's bullet trains or France's TGV. And according to the architect's plans Mr Taylor is holding, it'll run straight through his back garden. "Half the neighbourhood will be gone," he says. "We'll be paid what they call 'fair market value' for our homes and left to fend for ourselves. Of course, most people round here are under water on mortgages and can't get any more credit, so they won't be able to afford a new house. Most will end up in apartments and some people will be ruined."

Mr Taylor's troubles began in 2008, when California's voters approved plans to spend between $35bn and $40bn (£22bn and £25bn) on an 800-mile rail network linking San Diego, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Sacramento. Glossy PR brochures promised that space-age trains would cross the state at 220mph.

The plan would revolutionise infrastructure in a region that relies on clogged freeways and expensive planes, providing a major economic boost and creating (in the words of supporters) thousands of jobs in a modern reworking of FDR's "new deal" - which helped lift America out of the Great Depression.

Then reality struck. It quickly emerged that the rail line would run through several earthquake zones and at least one major mountain range. Thousands of homes would be destroyed and construction further complicated by California's highly strict environmental-protection laws and the myriad lawsuits they would no doubt spur.

Costs ballooned. In 2011, the High Speed Rail authority admitted that its proposed project would now cost more than $100bn and cover just 520 miles. It would no longer run to San Diego and Sacramento. This year, the authority changed its plans again: the network will now cost $68bn and cover a mere 480 miles. It will still connect Los Angeles with San Francisco, but will run in a circuitous loop - instead of a straight line - that heads inland via Bakersfield. And it won't be completed until 2035.

Then there's the small issue of money. Put bluntly, California doesn't have any. In fact, its government is billions of dollars in debt. The rail network must therefore be financed by a mixture of federal grants, private investment and bonds. And the only major cash injection that has been forthcoming is $3.2bn from Washington, which can only be spent in the depressed Central Valley region.

It has therefore come to pass that the first step towards California's swanky high-speed rail network will be a 130-mile section of stand-alone track, linking Bakersfield with a town just north of Fresno. This section will allegedly be completed in 2018 and cost $6bn: the $3.2bn federal grant plus $2.8bn of bond money authorised by the state Senate in a tight vote this month.Bakersfield has two claims to fame. Last year, Time magazine dubbed it the "most polluted city in America", thanks to its surrounding oil fields and position downwind of San Francisco's smoggy Bay Area. And in 2010, a Gallup poll revealed it to be the seventh "fattest" city in the nation, with 33.6 per cent of adult residents clinically obese. Meanwhile, Fresno was recently declared, in research of adult IQ rates carried out by The Daily Beast, to be the "dumbest" of the country's 55 largest cities.

To cynical observers, the notion of spending billions of dollars to link a famously fat city to a famously stupid one raises one simple question: why? Critics have widely dubbed it the "bullet train to nowhere".

California's political elite doesn't seem to care. Last week, Governor Jerry Brown threw a glamorous launch party in Los Angeles where he declared that "millions of people" would use the route. Unions say it will create thousands of jobs.

But public scepticism is growing, fast, shaped by a lobbying campaign by conservatives, who claim that spending tens of billions on a high-speed rail, when California faces a crisis in its public finances, represents the height of fiscal irresponsibility.

"Let's say you have an old car," says Girish Patel, a Bakersfield business leader who is one of the project's noisiest critics. "The tyres are shot, it's leaking oil. The engine's out. The tail light's shot. The front light isn't working. And if you were to pull up into a repair shop and say, 'Guys, I want a brand new stereo'. Would that make sense? Because that's what California's doing. It's a frivolous luxury."

Nimby-ish homeowners and entrepreneurs are littering the Central Valley with protest banners. "People round here are angry," says Aaron Fukuda, who has a small farm outside Hanford. "Owning a home is part of the American Dream and for that to be taken away by the swipe of a pen... it's not something you take lying down."

Around 450 homes and 1,400 people will be displaced by the 130-mile route, along with around 400 businesses employing 2,500 workers.Their likely route of opposition is at the ballot box. In 2014, Mr Taylor and his allies are sponsoring a ballot measure to stop construction in its tracks. Latest polls suggest it has a decent chance of passing. "If we have anything to do with it," Mr Taylor says, "The bullet train to nowhere is going exactly nowhere."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments