The Big Question: How did the polls get the result in New Hampshire so wrong?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

Because the UK went to bed on Tuesday night thinking that Barack Obama had pulled off a revolution in American politics. Obama, who had won unexpectedly well in the Iowa caucuses last week, then surged into the lead over Hillary Clinton in the New Hampshire opinion polls. By this week all the polls put him clearly ahead, one by 13 percentage points. Nor was it just the opinion polls and the exit polls in the New Hampshire primary. It was the higher attendance and enthusiasm at Obama's campaign events, compared with what all reporters agreed was a flatter and duller mood at Clinton's. Then we woke yesterday to the news that Clinton had won.

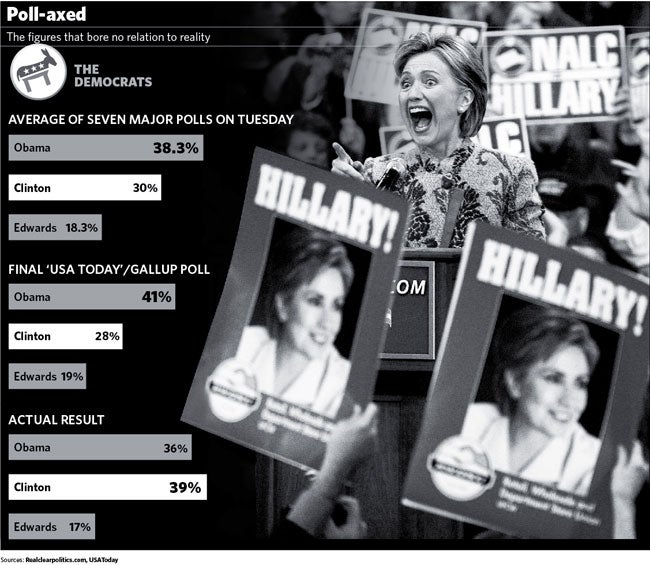

How wrong were the opinion polls?

The average of the polls conducted by seven different organisations on Saturday, Sunday and Monday had Obama on 38 per cent, Clinton on 30 per cent and John Edwards on 18 per cent. When people cast "real votes in real ballot boxes" on Tuesday, Obama was two points lower on 36 per cent, Clinton nine points higher on 39 per cent and Edwards a point off on 17 per cent. That is an average error for the two main candidates of nearly six points. In opinion poll history, that is a clunker. Often in a tight race, an error of two or three points can make all the difference, but getting within two or three points of the actual result is not bad for the fuzzy science of opinion research. The exit polls were wrong too, giving Obama a smaller four-point lead.

Are opinion polls inherently unreliable?

Anyone looking at opinion polls for the first time is taken aback by the apparent flimsiness of the data upon which such confidently-asserted predictions are made. How can you tell what might happen by telephoning 1,000 people at random across the whole country? In the case of state-wide polls in America, the samples are often much smaller. In New Hampshire, CBS News interviewed 323 LVs – "likely voters" – on Saturday and Sunday and put Obama seven points ahead. Rasmussen, on the other hand, interviewed 1,774 LVs. Rasmussen put Obama... seven points ahead. The theory is that, if a population is reasonably homogeneous, a surprisingly small sample, provided it is selected well and the results are adjusted for the known quirks of human behaviour, is adequate.

Could it be sampling error?

Any individual poll is subject to sampling error (it is quaint to British eyes to see the old "plus or minus four points" rubric on American polls – we gave up such pedantry some years ago), but the point about this week is that they all got it wrong. Undue attention was given to a Zogby poll for Reuters and C-Span that gave Obama a 13-point lead, but the other six final polls gave him leads of between five and nine points. However, the accuracy of the Republican primary opinion polls suggests that the pollsters' methods are fundamentally sound.

What about the Republican primary?

There were six polls conducted among likely voters in the Republican contest in the last three days of the campaign. John McCain's average support was 32 per cent; Mitt Romney 28 per cent; Mike Huckabee 12 per cent; Rudy Giuliani 9 per cent; and Ron Paul 8 per cent. McCain emerged five points higher on 37 per cent; Romney four points higher on 32 per cent; Huckabee a point down on 11 per cent; Giuliani and Paul were exactly in line on 9 and 8 per cent respectively. You will notice, as with the Democrats, that the numbers tended to be higher in the actual votes on Tuesday – that is because there were no "don't knows" in the polling booths. But in the Republican race, the shifts did not disrupt the basic pattern. Taking the "don't knows" into account, the opinion polls taken among Republican voters produced an average error between the two front runners of only half of one percentage point (in other words, the polls suggested a McCain margin of victory of four points; it was actually five). That's as spot on as opinion polls can be.

So what happened?

Whatever it was, it was a phenomenon restricted to those New Hampshire voters who took part, or said they were "likely" to take part, in the Democratic primary. Some people on the Democratic side behaved in a way that they have not behaved in recent years, and so the pollsters failed to adjust their numbers to reflect a new phenomenon. It seems likely that these unusual factors reflect the novelties of the candidates in the Democratic race – namely sex and race. There have been women in big-party presidential politics before, but running for only vice-president (Geraldine Ferraro in 1984). And there have been black candidates before, most recently Jesse Jackson (although Colin Powell nearly ran at least once), but never up front with a realistic chance of winning a main party's nomination.

Any theories behind the upset?

Within hours, the internet was awash with possible explanations for the discrepancy. First up was the "politically correct answer" theory: that some people said they would vote for the African-American candidate because they assumed that was what they were expected to say, and then voted for the white woman in the privacy of the booth. It is a version of the "shy Tory" phenomenon over here, when people did not want to admit that they would vote for the unfashionable Conservative Party.

It is questionable whether that is the case with Americans. Obama's supporters are more like Labour supporters in the Tory years – outspoken and enthusiastic, but much less likely to turn out when the time comes. The enthusiasm generated by the Obama campaign affected the answers some people gave to pollsters, but it was Hillary's supporters who were much more likely to turn out. Older people are more likely to vote, and it could be that her campaign energised older women especially in ways that the pollsters did not pick up.

Will future polls be more accurate?

Errors in opinion polls tend to arise when specific groups of voters start to behave differently. Over here, Labour supporters have become less likely than Conservatives to turn out to vote, especially in safe seats. Hence, the opinion polls have tended to overstate Labour's share of the vote for at least the last three general elections. It's doubtful that the voters of New Hampshire's Democratic primary are very different in their electoral attitudes from those of Michigan (15 January) or even South Carolina (26 January) and Florida (29 January). So, given that there is no time for the pollsters to change their methods by then, it might be wise to add nine points to Hillary Clinton's opinion poll numbers, and deduct two from Obama's.

Will the pollsters and pundits get it wrong next time?

Yes...

* Errors in opinion polls tend to be consistent, so they will go on getting it wrong as long as Obama and Clinton are the main candidates

* The time difference will be just as cruel to the British media in Michigan, South Carolina and Florida – and more so in California

* Everyone will overreact and write Obama off completely, when he was only three points behind in one of Clinton's strongest states

No...

* Errors in opinion polls tend to be consistent, so we should be able to make some allowances for biases in the Democratic race

* No one is going to make any outcome-specific generalisations for a long time – not until at least the middle of next week

* Everyone will end up telling us next to nothing about what is likely to happen, thus making the election seem more exciting

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments