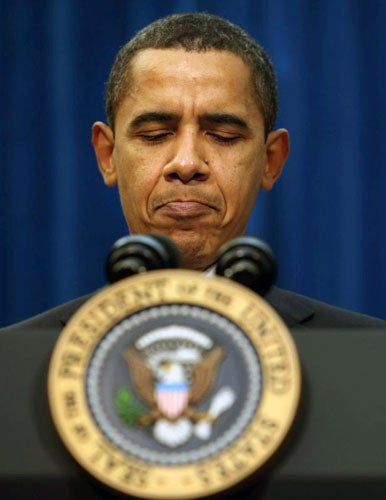

The $165m bonus question threatening Obama's rescue deal

National outcry at payouts to traders who helped bankrupt AIG may hurt President

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There have been financial show trials aplenty on Capitol Hill since the crisis engulfed the US, but none surely as pivotal as today's scheduled grilling by a Congessional panel of Edward Liddy, the chairman of the AIG insurance giant whose $165m (£117.5m) bonus payments to certain executives suddenly threaten to derail President Barack Obama's entire economic strategy.

Amid the trillions of dollars spent or promised to rescue the US economy, the bonus money is a mere speck of dust. It is minuscule, set alongside the $170bn of bailout funds AIG has already received, or the staggering $61.7bn the company lost in the final quarter of 2008 alone. But the payouts have unleashed a flood of national outrage that, if it does not soon abate, could turn Congress against the President, send his popularity among the people tumbling, and sweep away his plans for economic recovery.

In politics, power is the perception of power, and Mr Obama still has a good deal of that essential commodity, a 60 per cent approval rating, according to the latest polls. But the AIG affair, now the lightning rod for public disgust with Wall Street and all its works, is exposing the limits to that power.

Visibly furious, the President ordered Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner on Monday to "pursue every legal avenue" to claw back the bonuses (which seem to have been paid just before the weekend). "How do they justify this outrage to the taxpayers who are keeping the company afloat?" Mr Obama asked.

That, of course, is the question Mr Liddy must answer when he appears before the House sub-committee on capital markets. But in a slightly different, and scarcely less embarrassing form, it is starting to lap at the doors of the White House as well.

As commentators and administration critics alike point out, the existence of bonuses for workers in AIG's financial products unit that brought the group to the bankruptcy, has been known about for months, well before the Obama administration came to office in January. Why then did it not take action to stop them before they were paid, as part of the most recent $30bn of government aid for AIG, unveiled a fortnight ago? "Where was the Secretary of the Treasury?", Richard Shelby, the top Republican on the Senate Banking Committee, asked yesterday. "Why didn't Treasury step in and let the American people know, just try to block it?"

The awkward answer is, the Treasury probably could not have blocked it. Government lawyers have apparently concluded that the bonus contracts, negotiated a year ago, are legally binding. To tear them up now might not only generate a a slew of lawsuits, but also raise fears that other contractual obligations undertaken by the government and other parties in the crisis could be ripped up without warning.

Others argue the bonuses may be essential, to keep expert staff at the unit responsible for the reckless trading. "The sobering thought is that AIG built this bomb," Andrew Ross Sorkin wrote in The New York Times this week. "And it may be the only outfit that knows how to defuse it." But such subtleties are lost on the population at large, battered by job losses, a home foreclosure crisis and the evaporation of trillions of dollars of personal wealth on the stock market. Nor do they elicit the slightest sympathy on Capitol Hill.

Yesterday, Congressional Democrats were vowing that one way or another, the bonuses would be clawed back, possibly even by a change to the tax code, making all bonuses over $100,000 paid at companies that had received federal bailout money taxable at 100 per cent.

For his part, Harry Reid, the Democratic majority leader in the Senate, is promising to force AIG employees – said to number about 400 – who had received the bonuses to give some of the money at least back to the Treasury.

Perhaps more realistically, Nancy Pelosi, the House Speaker, tried to shame the bonus recipients into submission, calling on those "whose irresponsible risk-taking had brought our financial system to the brink of collapse" to voluntarily give up these "excessive retention payments".

But the biggest danger for Mr Obama comes from the opposition Republicans. After their stinging defeat in November's elections, Republican leaders are riding the popular fury at AIG and the banks to rebuild the party's appeal. Their biggest opportunity will come when the administration asks Congress for yet more funds to prop up financial institutions, as it almost certainly will in the months ahead.

Back in December, a narrow majority of Americans approved the government bailout programme. Now, according to the same CBS poll, they are opposed by a solid majority, of 53 per cent to 37 per cent. Three-quarters of the public believe the banks' problems were caused by the greedy and irresponsible conduct of management. These findings explain Mr Obama's chastising of AIG. But they also suggest that Congress could be extremely unwilling to cough up more bailout money, just when Fed chairman Ben Bernanke, the senior presidential economic adviser Larry Summers and others warn that until the financial sector is made healthy again, the broader economy will not recover.

Republicans are using the imbroglio to reinforce their argument that the government should stop meddling in the private sector. Having voted against last month's $787bn stimulus plan, they are likely to take the same approach to a new bank bailout. And this time, some Democrats seem inclined to join them.

"The American people don't know what to believe about all this, and neither do I," said Paul Kanjorski, the Democratic chairman of the House committee that will interrogate the AIG chief today. "I'm losing patience with the whole operation."

For President Obama, the stakes grow higher every day. Fairly or unfairly, the AIG afffair, and by extension the other woes of the banking and financial system, risks being seen no longer as a poisoned inheritance from the Bush administration, but as an "Obama problem". Unless a line is swiftly drawn under the episode, he may not be able to refocus attention on his far more important budget proposals. These pave the way for sweeping reforms of health care, education and energy policy that will redraw the national economy. But the longer they linger in abeyance, the less likely they will pass Congress in anything like the form they will arrive in.

Crippled insurer pays out: How employees were rewarded

Seventy-three employees of AIG's catastrophic derivatives trading business have been given "retention bonuses" of more than $1m, including 11 people who left the company.

Those were yesterday's revelations, the latest in a trickle guaranteed to stoke the fury of politicians and the public, who face paying out $170bn to wind down one of the most disastrous business ventures in financial history.

AIG says it needs to keep paying these traders because only they know how to unpick the costly insurance contracts they wrote for trillions of dollars in mortgage investments and other derivatives. The public is asking why.

After all, it was their miscalculations that brought a once-proud insurance company to its knees and threatened to wreck the entire global financial system.

The traders wrote insurance contracts called credit default swaps, in effect insurance designed to pay out only if a bond defaulted. In the financial meltdown after Lehman Brothers collapsed, many more bonds threatened to do so, and AIG didn't have the money to meet its obligations.

Stephen Foley

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments