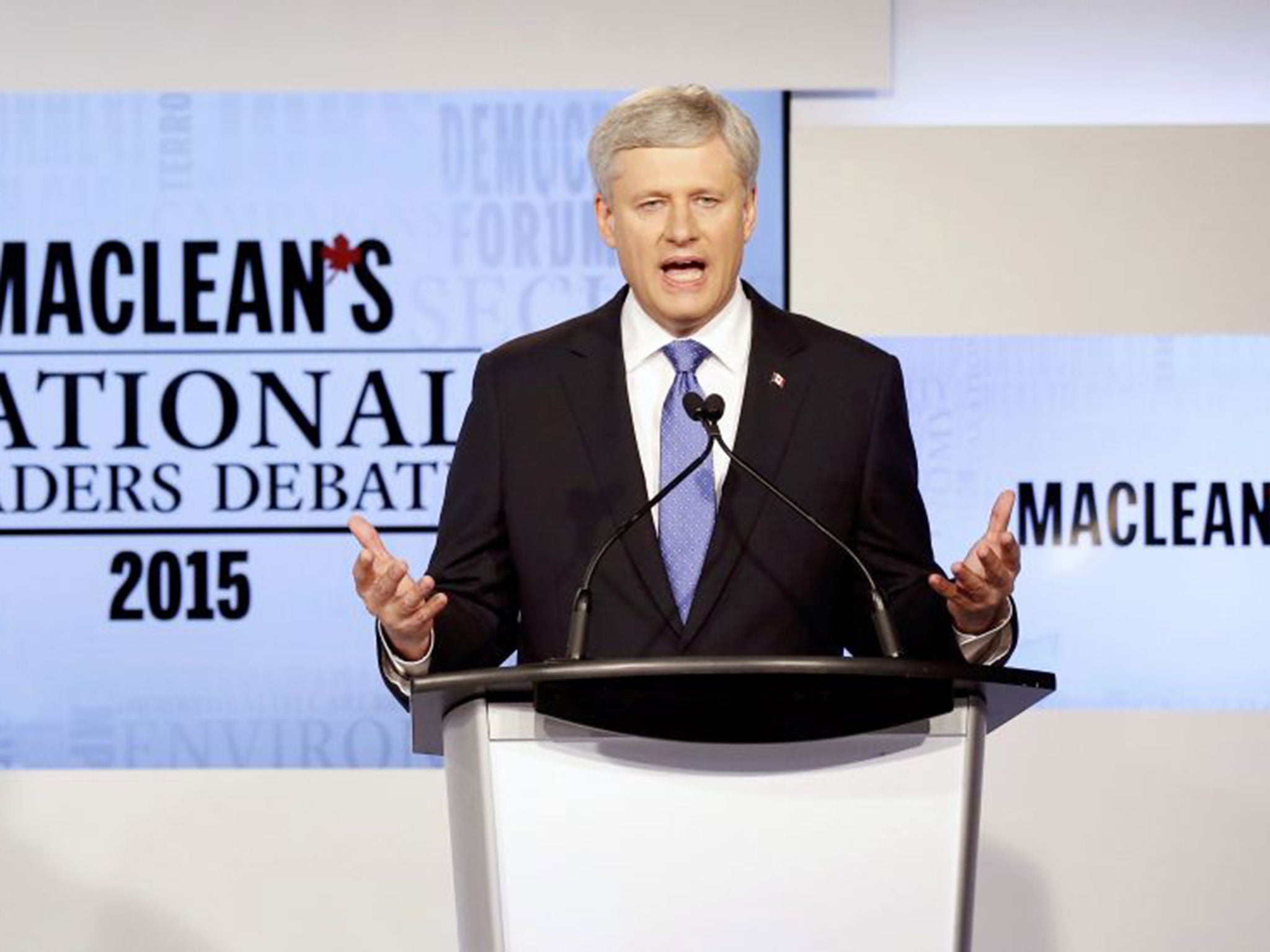

Stephen Harper: Canadian Prime Minister accused of taking country too far to the right

Harper's personality and policies have angered and alienated a broad swathe of Canadians

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Secretive, vindictive and patronising are not words in keeping with the popular stereotype of Canadians. Yet that’s how citizens of the world’s second-largest country are increasingly portraying the Prime Minister, Stephen Harper, these days.

The Conservative leader, who has been in charge for nine years, called an election on 2 August with hopes of extending his right-wing reign. But his personality and policies have angered and alienated a broad swathe of Canadians.

A mock campaign poster making the rounds on social media sums up the collective mood of his critics, using his image – complete with his trademark hockey-helmet hair – in the same style as Barack Obama’s 2008 election poster, but replacing the word “hope” with “nope”.

The week has certainly not gone smoothly for Mr Harper. He started it by releasing a video of himself describing his love for the entertainment streaming service Netflix, and his particular fondness for the show Breaking Bad. In a move clearly designed to make the most of the popular service’s name, he said that his party would never implement a tax on it, or other streaming services, unlike “some politicians” who might be looking to make the move. But the Prime Minister was undercut by the fact that, after the message was released, both the Liberal Party and the New Democratic Party – the main rivals – said that they, too, had no plans to do such a thing.

The hashtag #HarperANetflixShow then started up on Twitter – with users imagining (mainly mockingly) artwork and titles for a show starring Mr Harper if one were to run on the service.

In the election, called for 19 October, Mr Harper faces the Liberal Party leader, Justin Trudeau, who’s trying to follow in the footsteps of his father, Pierre. The Conservatives have attacked Mr Trudeau, 43, who had polled previously as the frontrunner, for being “just not ready” to lead.

Mr Harper, 56, has been using only his rival’s first name to portray him as merely a boy. His other main competitor, the New Democratic Party’s Tom Mulcair, 60, is referred to by his last name – the strategy being to divide the opposition vote. Recent polling has shown the gap between the Conservatives and the New Democrats as close, with the Liberals in third place.

On Thursday, Mr Harper faced off against Mr Trudeau and Mr Mulcair, as well as the Green Party leader, Elizabeth May, in the first televised leaders’ debate of the campaign. While nobody was able to land a knockout blow, Mr Harper faced criticism from all sides on his handling of the economy. “Mr Harper, we really can’t afford another four years of you,” said Mr Mulcair.

While Mr Harper has been in charge, the Canadian dollar has plummeted and the economy is in recession. His focus on making the Great White North a petrol state by exploiting the oil sands in Alberta at the expense of the environment is blamed by some for this. Nevertheless, during the debate he defended his job-creation figures amid a weak global economy and while campaigning he has emphasised a balanced budget and tax breaks. A poll in May, however, found that 73 per cent of respondents thought their economic fortunes had not improved since 2010.

Dan O’Halloran, 73, a retired civil engineer who lives in the east coast city of Halifax, said he finds Mr Harper too cold and controlling. “He comes over as rather distant and aloof – not a character one would warm to quickly,” Mr O’Halloran said as he set out for an afternoon cruise from Halifax Harbour.

If Canadians are seeing less of themselves reflected in their country’s leader – an example being Catherine Finn, a 72-year-old who died last month in Toronto, who even had an obituary urging people to “do everything you can to drive Stephen Harper from office, right out of the country, and into the deep blue sea if possible” – could this spell the end of the Harper era?

“Some of the opposition is based on policy objections, and some on simple partisanship and politics,” Peter Loewen, who teaches political science at the University of Toronto, said. “A good bit of it is just fatigue – he’s been prime minister for nearly 10 years and that’s a long run for any politician. But, above all that, he is a person who some people view as cold and distant, even conniving.”

Mr Harper has also called the election early, making the campaign twice as long as usual to benefit his party with its larger contingent of wealthy supporters. “The Conservatives have more money in the bank and can outspend the two main opposition parties,” Peter McKenna, a political science professor at the University of Prince Edward Island, said.

Under Mr Harper, Canada has moved to the right in most areas. A largely liberal nation where Greenpeace was formed and the concept of peacekeeping created, it was the first to withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol, opted out of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification and has zealously supported Israel.

Mr McKenna said Mr Harper has largely abandoned the country’s tradition of international diplomacy and sees little need to get along with other nations or respect the UN.

And Mr O’Halloran said he doesn’t agree with Mr Harper’s shift to hardline right-wing policies, particularly in relation to the Middle East. “He is far too one-sided in favour of Israel and against the Palestinians, and I believe Canada should be more balanced.”

At home, Mr Harper has reduced the size of government while being pro-military, hard on drugs, tough on crime, and is accused of being a fearmonger about foreign terrorists and dismissive of the environment – even forbidding some federal scientists from speaking out publicly.

And last month, Mr Harper’s government succeeded in preventing Canadians from voting if they’d been living outside the country for five years. This was too much for the veteran actor Donald Sutherland.

“This new ‘Canada’, this Canadian government that has taken the true Canada’s place, has furiously promoted a law that denies its citizens around the world the right to vote,” Sutherland, who grew up in Nova Scotia, wrote in The Globe and Mail. “Why? Is it because they’re afraid we’ll vote to return to a government that will once again represent the values that the rest of the world looked up to us for? Maybe.”

“Canadians are starting to see through the cynical political nature of some of these moves,” said Mr McKenna. “Harper’s anti-democratic and authoritarian streak have also rubbed Canadians the wrong way. They want something different. He will have a harder time this time.”

But what will be the outcome? “There is a fair amount of talk about change, but in politics a week is a long time and I would not make any predictions,” said Mr O’Halloran.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments