Special report: Martin Luther King is today revered in death as he was feared in life

The sniper’s bullet only served to increase his power, writes Rupert Cornwell

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Only a small handful of presidents – Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, perhaps Franklin D. Roosevelt – now occupy a more exalted place in America’s pantheon of national heroes than Dr Martin Luther King Jr.

The black civil rights movement threw up many leaders, from Ralph Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth, Dr King’s associates in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), to Rosa Parks and John Lewis, as well as more militant and confrontational figures such as Louis Farrakhan, Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael. None, though, has ever commanded the veneration accorded to Dr King.

Forty-five years after he was cut down by a sniper’s bullet on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis on 4 April 1968, his reputation and myth have steadily grown. When he died he was still feared and detested by many whites as America’s old racial order was starting to crumble. An infinitesimal minority of bigots still feels that way. But today, streets, boulevards and buildings across the country bear his name – as does a full federal holiday on the third Monday of the new year, marking 15 January 1929, the day he was born.

Dr King’s identification with the civil rights movement began in Montgomery, Alabama, where he became a pastor in 1954. The following December, a black seamstress named Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat at the front of a bus to a white man, and was arrested. There followed the Montgomery Bus Boycott, organised by Dr King, one of the earliest civil rights protests.

Over the next decade, he became the most influential force in the movement. In 1957, he helped found the SCLC and became its first president. He was present at many of the confrontations that thereafter made headlines, from Albany in his native Georgia to Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, when the brutal repression of generally peaceful protesters by the city’s police chief, Eugene “Bull” Connor, made headlines around the world.

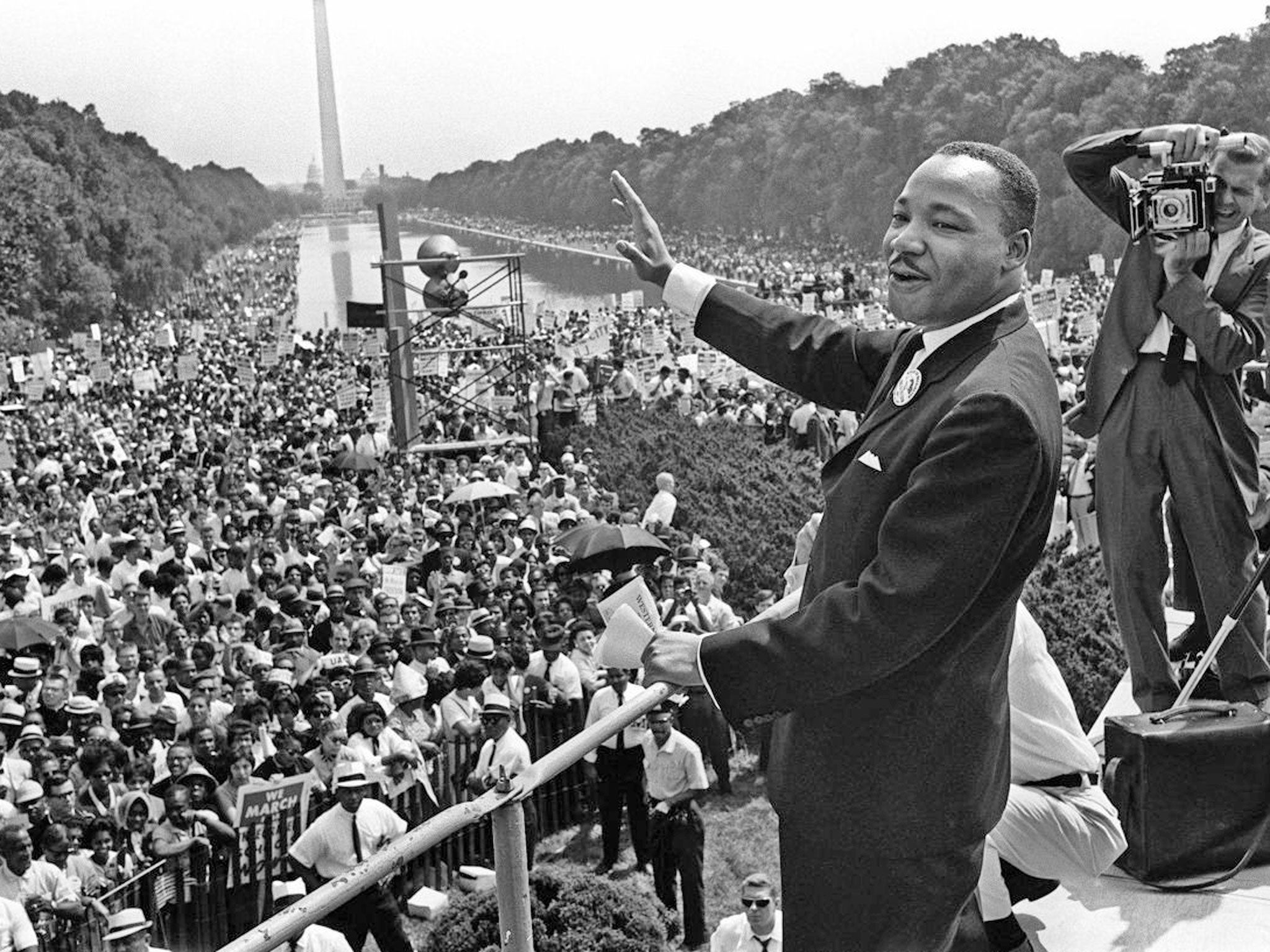

Unlike Albany, Birmingham achieved results that contributed to a rising tide of expectation as Dr King led the celebrated “March on Washington” on 28 August 1963. Originally intended to highlight the economic, rather than political, woes of blacks in the southern states, the mass rally on the Mall is forever remembered for Dr King’s electrifying “I Have a Dream” speech.

Thereafter, he was the unquestioned leader of the mainstream civil rights movement. Others advocated more forceful means, but Dr King remained true to his principle of non-violence. The protests he organised might have been intended to provoke, but they were peaceful, and his insistence was always to turn the other cheek. At times this strategy seemed to falter, while Dr King attracted the suspicion (and close surveillance) of the FBI and the Johnson administration with his opposition to the Vietnam War.

Today, however, Dr King is an ever-more admired figure, for his insistence on non-violence, his personal courage, and the soaring, relentlessly upbeat oratory that reflected his country’s innate optimism in spite of all that the most turbulent decade in modern US history could throw at it.

By the time of his death, the main legal building blocks of the civil rights revolution were in place: the 1954 Supreme Court ruling desegregating schools, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, outlawing discrimination in every part of American life, including the ballot box. But the race riots that erupted after his murder, in cities across the country, were evidence of how much still had to be done to bridge the gap between promise and reality.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments