Schoolboy killed playing the 'choking game' as parents warned

'What we are seeing in terms of children dying is only the tip of the iceberg of a major problem which to a large extent is unrecognised'

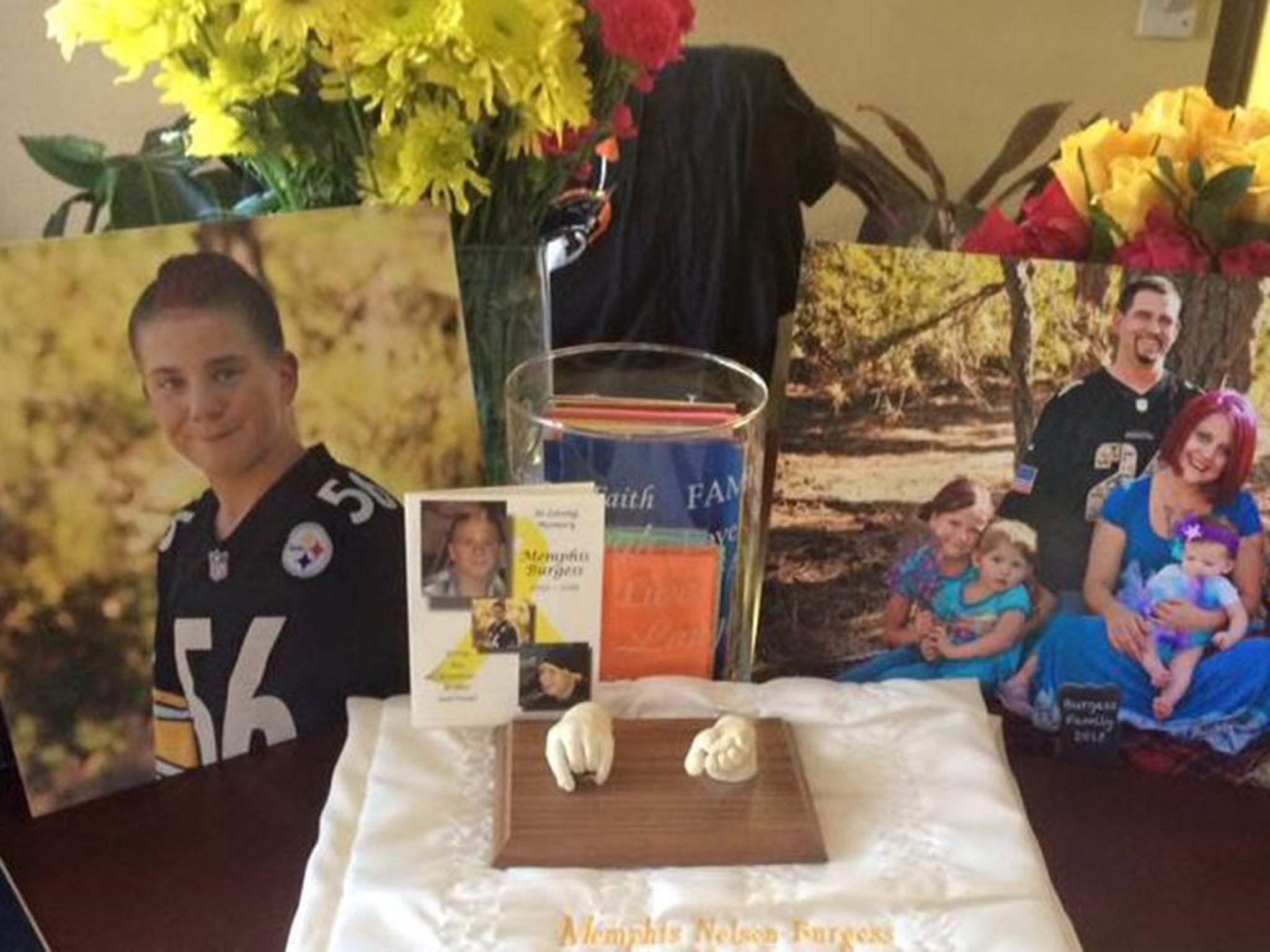

This time, it was 13-year-old Memphis Burgess.

The Colorado Springs seventh grader with the purple Mohawk and goofy grin was discovered in his closet 11 days ago, crouching on his knees, his face against the wall, as still as death.

“I thought he was messing with me,” his father, Brad Burgess, told KKTV. “I shook his shoulder. That’s when he turned around I noticed he was all blue and not breathing.”

A soft rope lay on the floor nearby.

The Burgesses don’t believe their son killed himself intentionally. They think that he wrapped the rope around his neck in an attempt to stop the flow of oxygen to his brain for a brief high. It’s a pastime known at Memphis’s school and elsewhere as “the choking game.”

This time it was Memphis Burgess. Nine years ago it was William Bowen, a 15-year-old from Frederick County, Maryland, who accidentally asphyxiated himself with a terrycloth towel. Almost a decade before that, it was Judson Thompson, 11, who was found strangled by a dog collar in his home in Manitoba.

All told, the game is thought to be responsible for more than 1,000 deaths since 1934, according to GASP, an advocacy group that aims to put a stop to the activity. The victims are almost always kids like Memphis: teenagers trying it alone, unaware of the fact that their “game” has a long and deadly history.

While the “choking game” has been around a long time, some experts fear that it could become more common because of social media, including YouTube videos portraying it.

Martha Linkletter, a 37-year-old pediatrician in Ontario, said her patients are often surprised that she’s heard of the game when she asks about it.

“They can’t believe this super-old pediatrician knows about it. They think it’s this subversive, underground thing, that ‘no parents even know what we’re doing,'” she told The Washington Post.

But Linkletter, who co-authored a study about YouTube and asphyxiation games, recalls people playing the “game” at slumber parties when she was a child. In fact, people have been asphyxiating themselves for centuries, even millennia — not seeking death, but something at its very edge, the dark, dreamy high of almost-oblivion. It’s been part of religious ceremonies and occult rituals, even sex — in the Victorian era, men would visit “Hanged Men’s Clubs” for erotic encounters that involved depriving their brains of oxygen. Then as now, the pursuit was sometimes fatal.

But cases of children taking asphyxiation to the point of death — at least, documented cases — are more recent. A 1951 study in the British Medical Journal detailed a disturbing school kids’ game called “the fainting lark”: a boy would sit on his haunches, take 20 deep breaths, then stand and plug his nostrils with his fingers and attempt to blow out deeply. The effect would allegedly make the teen pass out for a minute or two, purportedly for the amusement of his friends.

Since then, the game has taken a variety of names and forms: “choking game,” “knock out game,” “tingling game,” “space cowboy,” “space monkey,” “cloud nine,” “black hole,” “suffocation roulette.” In locker rooms or at slumber parties, one kid might forcefully breathe out over and over again while another presses on her chest, preventing her from breathing in. The tactic changes the pH of the blood, causing dizziness and euphoria, but it also causes hypoxia, or a dangerous lack of oxygen in the brain.

Or they might tie a ligature — a rope, towel, dog leash, scarf — around the player’s neck, tightening it until he’s nearly unconscious. At that point, the ligature is loosened, the player breathes in, and precious oxygen floods his brain, bringing him back from the brink.

To an outsider, the game sounds horrifying, and so extreme that only the most irrational person would try it. But it doesn’t seem that way to a teenager, Linkletter said.

“No parent thinks their kids are asphyxiating themselves until they pass out; that’s horrifying to parents,” Linkletter said. “But this is the age where kids are engaging in high-risk behaviors. That’s just what they do.”

Various surveys have found that 5 to 10 percent of middle schoolers have played the choking game.

Self-asphyxiation has a reputation as “the good kid’s high,” according to Salon — a way to achieve euphoria without drugs or alcohol. And discussion of the game online can make it seem like a joke.

While working as a pediatric resident several years ago, Linkletter surveyed dozens of YouTube videos of the “choking game” for a study in the journal Clinical Pediatrics.

“They make it look like a funny, awesome activity,” she said of the videos. “Everybody is laughing, giving high fives, even when someone is having a hypoxic seizure on the ground.… That can normalize it. It makes it seem like everyone is doing this.”

Meanwhile, many parents and pediatricians aren’t even aware of the choking game’s existence. And if they are, they assume that their child would never play it.

“It is very difficult to get at the extent of the problem because people are very reluctant, both from the medical end and the family end, to acknowledge that this practice is taking place,” said R. Carl Westerfield, former dean of education at Lamar University in Beaumont, Tex, told The Washington Post in 2006. “It’s in the closet.”

Nearly a decade later, that statement remains more or less true.

It doesn’t help that there is still little comprehensive research on the choking game — a review of available research published earlier this year found “limited and little consistent evidence about the prevalence, associated risk factors and levels of morbidity and mortality associated with engagement in [self-asphyxial behaviors]” despite the fact that it has been around for years.

Estimates of the number of choking game fatalities vary widely — 2008 CDC report put the number of deaths at 82 over the course of 12 years; GASP (whose name is an acronym for “games adolescents shouldn’t play,” counted more than 600 in the same period. Additionally, many asphyxiation deaths that may have been accidental are ruled suicides — unless parents and police are somehow aware of the choking game, they’re likely to assume that the death was intentional.

“What we are seeing in terms of children dying is only the tip of the iceberg of a major problem which to a large extent is unrecognized,” wrote one researcher in 2009.

But studies do seem to agree that most choking game fatalities come when a person attempts it alone.

“There’s no one to relieve the pressure when it goes too far,” Linkletter said.

These deaths appear to be happening more often, Linkletter said, perhaps in part because teenagers are more likely to find out about the choking game online and try it on their own. GASP has counted 672 choking game deaths in the past 10 years, more than twice as many than occurred in the decade before that.

But reports of deaths may also be more common because people are more aware of it, and less likely to rule an accidental death a suicide. There are stories from survivors like Levi Draher, a San Antonio teen who emerged from a three-day coma after strangling himself with a rope slung across his bed frame in 2006 to become a scared-straight motivational speaker, reciting his tale of near-death and resurrection in high school auditoriums across the country. Lifetime made a movie about the game in 2014 (though it’s not clear how many 14-year-olds a Lifetime movie might reach).

And then there are those who know someone who has died — relatives and friends who swear to stop the game that cost them a loved one’s life.

At a service for Memphis Burgess on Friday, one of the boy’s friends approached the grieving mother and confessed that he, too, had tried the choking game.

“He promised he would never play again,” Annette Burgess told KKTV. “So I know that [Memphis’s] life is at least going to have an impact.”

Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies