Republican Debate: Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio and the significance of the 'He doesn't speak spanish' GOP jibe

What Cruz said was the kind of grammatically unorthodox thing you might say when flustered, when non-fluent and or when trying to sound tough

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is a dark period in American history. It's one to which some Americans seem eager to return. It's one when people were barred, shamed or even punished for speaking languages other than English. That was especially true outside the home.

Speaking a foreign language or limited English was very widely believed to be an indicator of suspect national loyalty, limited intelligence or ability. Speaking a foreign language simply was not regarded as a useful skill.

And there were a whole range of dominant but nonetheless inaccurate theories about the way that children and adults actually acquire a second or third language that claimed an English-only lifestyle was best. Schools, businesses and all sorts of institutions in the Southwest and West barred kids from speaking Spanish and encouraged their parents to do the same at home.

Even worse, Spanish-speaking in particular became a target of American cultural purists who subscribed to some seriously circular logic. These folks — the majority of America — truly believed that which was white was that which was American. And therefore, that which was culturally white should be emulated and, when necessary, enforced.

That sense of cultural and intellectual superiority also provided some of the justification for a everything from voter suppression to economic exclusion, school segregation and human rights abuses. Just in case you are not aware, like African Americans around the South and Southwest, Mexican-Americans in those regions were almost uniformly subject to poll taxes and civics tests designed to keep Latinos from voting.

That went on in some places as recently as the 1960s. And there are Latinos living in the Southwest who can tell you stories right now about widespread paddlings and corner-time dolled out by teachers and nuns for speaking Spanish at school as late as the 1970s. In 2006, a Kansas family with a last name that happens to be Rubio filed suit after school officials there tried some of the very same tactics. So, while less common, some remnants of these ideas remain.

It is nothing to celebrate. It has left the United States far behind other countries in terms of the share of adults who can operate in two languages or more. Millions of Americans who could have grown up speaking any number of languages and reaping the possible brain-boosting simply did not.

(Of course, some still dispute the idea that bilingualism is good from the brain. Click here and the link below for more on the two views.)

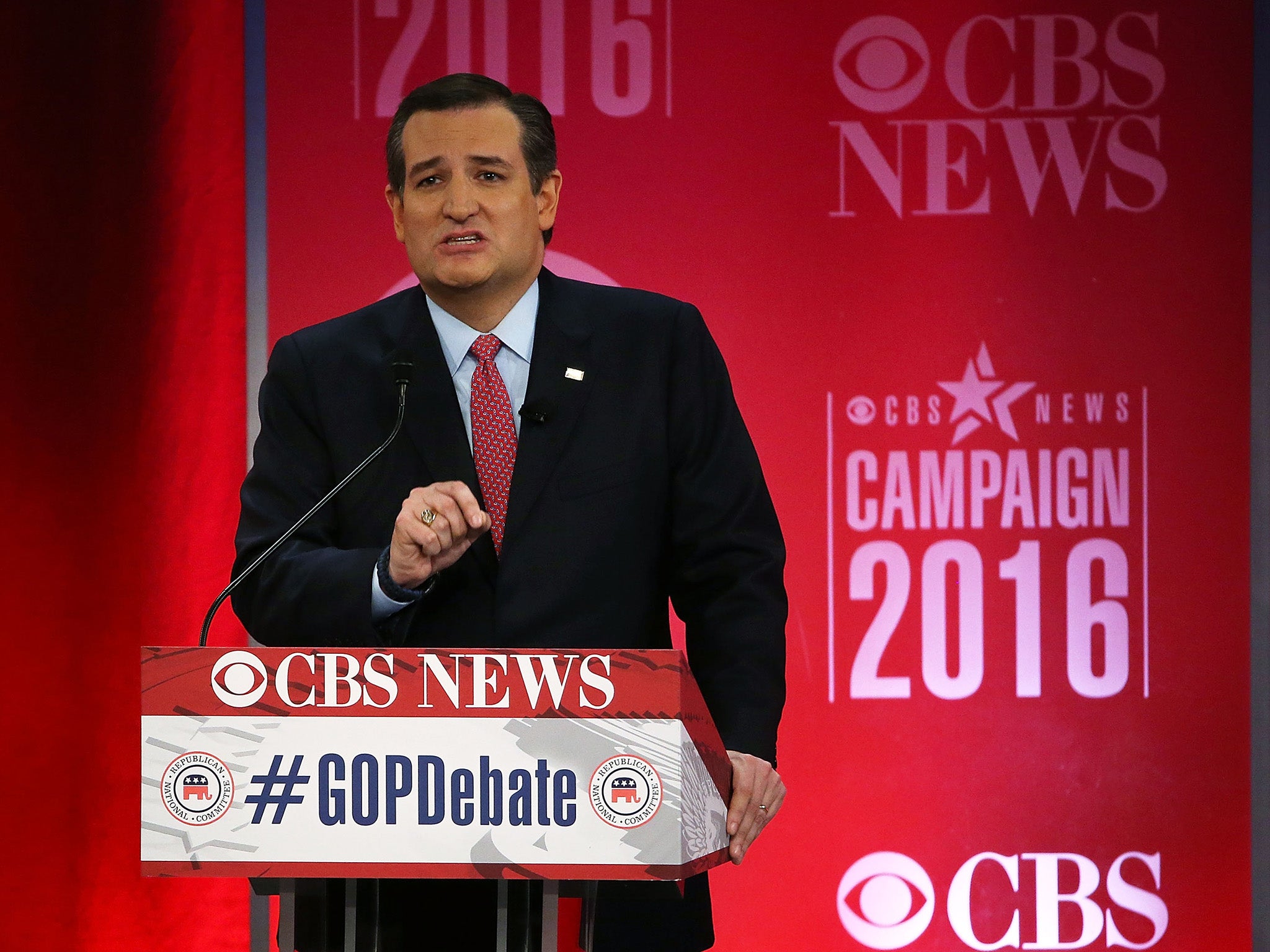

Now what, you ask, does that have to do with a heated moment during Saturday's Republican debate during which Ted Cruz started speaking Spanish?

Well, possibly, quite a lot. Cruz may have been born in Canada — much to Donald Trump’s delight — but he grew up in Texas during the final decades when the ideas described above could be repeated in public without so much as a single side eye. Cruz has said before that his Spanish is “lousy,” and back in 2012 when Cruz was running for the Senate, his Spanish-speaking opponent tried to needle Cruz into a Spanish-language debate.

Cruz refused, saying something that lots of Texas Republicans seemed to like: Most people don’t speak Spanish. The goal was probably to throw the championship debater, Cruz, off his game, but also to associate Cruz with a particularly modern kind of alleged cultural failing. Cruz’s opponent knew that might have meaning in a state with a lot of Latino voters.

The inability to speak fluent Spanish has become a source of embarrassment for some Latinos. Sometimes, that’s the subject of something a little more serious than teasing. There are some — emphasis on some here — Spanish-speaking Latinos who regard the inability to speak Spanish as an indicator of capitulation to old-school, self-loathing, and bigotry-fueled pressure to assimilate by emulating white Americans.

Now, some things in American life have so changed that, for many months, there were more than a few Republican politicos who regularly insisted that the ability of former Florida governor Jeb Bush (R) — the white son and brother of a former president, married to a Mexican-American — to speak Spanish was going to help him win a big chunk of the Latino vote. So let's not deny that there's a politics of language in 2016.

That brings us to that moment in the debate.

Cruz told viewers that Rubio made statements on Univision — the nation’s highest-rated Spanish-language network — indicating that Rubio, if elected, would not rescind one of Obama’s most consequential executive orders. It gave a deportation reprieve to millions of so-called “Dreamers.” The implication was that Rubio says and does things behind your backs, overwhelmingly white and English-Speaking only Republican voters, of which you may not be aware.

Rubio didn’t clearly deny the claim. But he sure did lash out in one heck of a way.

“Well, first of all, I don’t know how he knows what I said on Univision, because he doesn’t speak Spanish,” Rubio said.

Rubio, a son of Cuban immigrants, may be only a year younger than Cruz. But when it comes to the social politics around Spanish that shaped his formative years, things really could not be more different. Rubio spent most of his childhood in South Florida, a region where Cuban-American cultural influence, respect and perhaps even dominance made the act of learning, speaking and transmitting Spanish to subsequent generations fundamentally different. Bilingualism was expected. It’s long been understood as a meaningful skill, but also a way to build, preserve and promote Cuban-American identity.

Rubio almost certainly knows all about the full array of fraught social, political and emotional issues that rotate around Spanish-speaking skills for some Latinos. He almost certainly heard about that most-awkward and, shall we say, ill-advised moment back in May when Bloomberg’s Mark Halprin tried to force Cruz to speak Spanish on demand during an interview. Halprin seemed to think Cruz should prove his Latino bona fides and language was the way to do it.

And, Rubio, like Cruz’s Senate challenger, probably saw it as a great way to throw Cruz, the master debater, off-kilter, maybe even to change the subject. They were, after all, tangling over one of the issues about which polling data indicates a goodly portion of Republican voters may have some doubts about Rubio. He is not a solid immigration hard-liner.

Likely sensing some of all of this, Cruz absolutely clapped back. This is something he’s been goaded about and even criticized for in the past. You can basically see that in the briefly crestfallen look on his face.

The only real surprise was that Cruz’s reply came quick. And, it came out in Spanish.

"Marco, si quieres ... ahora el mismo, díselo ahora, en Espanol, si quieres." (That translates roughly to "Marco, if you want ... right now, say it right now, in Spanish, if you want.")

So, we’re going to have to be frank and tell those of you who don’t speak Spanish that what Cruz said was the kind of grammatically unorthodox thing you might say when flustered, when non-fluent and or when trying intentionally to sound tough. We can’t say for sure which of those three really dominated Cruz’s response here. Only Cruz really knows.

(Side note: Do take a moment to view the video up above. Behold the face and body language of Donald Trump, who is standing between Cruz and Rubio during this exchange. Volumes could probably be written about it alone. There will, almost certainly, be GIFs.)

For now, we’ll leave you with this: America, this was one of those moments full of history and emotion and deep social meaning that a good portion of the audience likely did not fully comprehend. But, it’s worth noting because that entire exchange was made possible by decades of misguided, scientifically unsound and bigoted thinking that plenty of Americans continue to laud every day.

Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments