Meet Redneck Revolt, the radical leftist group arming working-class people so they can defend minorities

The Independent spent the day on Long Island with members of the armed leftist group

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is 9am on a Sunday, and a group of radical leftists are gathered at a shooting range in rural Long Island having target practice.

From a distance, it looks like a scene from any small, conservative town in America: A group of guys palling around in a snow-covered parking lot, taking turns firing down the range while swigging cups of hot coffee to ward off the cold.

Up close, however, it looks quite different. The guns are not American-made, but Russian; forged in the Soviet era. One has a hammer and sickle etched into the bolt. The men are genial but reserved, keeping their distance from the other groups around them. And one of them is complaining bitterly about his coffee. It came in a Styrofoam cup.

“What’s wrong with Styrofoam?” his friend wants to know.

“It takes, like, 50,000 years to decompose!” he replies.

The environmentalist’s name is Mike, a Long Island native and self-described Marxist-Leninist. He was born in conservative Suffolk County to a clerical worker and industrial maintenance technician. He says he grew up “dirt poor," and was radicalised by a lifetime spent thinking: “There’s got to be an answer for why this is so shitty.”

One night earlier this year, after a couple of beers, Mike decided to find some like-minded radicals on Long Island. He posted on a Facebook page called “Long Island Socialists,” and heard back from the page’s administrator almost immediately. That’s how he found Redneck Revolt, and how came to be standing on the gun range that day.

Redneck Revolt is a national activist organisation that advocates for the downfall of capitalism through the elimination of racism. Its founders believe strongly that working-class liberation can only occur when workers unite, regardless of race. So in 38 different locations around the country, Redneck Revolt mobilises poor, rural white people to stand up for people of colour.

And yes, they carry guns.

Indeed, Redneck Revolt may look like many other social-justice groups – its website contains frequent mentions of “trigger warnings” and “solidarity” – but it is far from it. The members of Redneck Revolt don’t want you to sit in a circle, hold hands, and sing Kumbaya. They want you to know you have an enemy – it’s just not who you think it is.

In an open letter that the group frequently uses for recruitment, it urges working-class white people to “look around” and wonder: “Who lives in the houses or trailers in the same neighbourhoods as us? Who works next to us in the factories, or cooks alongside us at the restaurants?”

“It sure as hell isn’t rich white people,” the letter continues. “It’s Brown people, Black people, and other working-class white people. They are the ones that are in similar situations to us, living paycheck to paycheck, stretching to feed their families like we do. So why then would we view them as so different from us that we literally view them as our enemies?”

The message seems to be catching on. From the group’s humble beginnings in Colorado and Kansas, it has spread to nearly 40 branches nationwide. Members participate in everything from community gardens to counter-protests at right-wing marches. Some even try to find new members at these marches, in a process known as “counter-recruiting”. The group counter-recruits in many traditionally white spaces, such as NASCAR races and gun shows.

The Suffolk County branch, to which Mike belongs, isn’t big on counter-recruiting these days – they’re getting enough interest as it is. Instead, they host potlucks with neighbouring leftist organisations and protest prison conditions with Black Lives Matter. Last month, they hosted a vigil for victims of the opioid crisis with members of the Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL). They also grow their own community garden, and go out every Thursday to feed the homeless.

But Kevin – another Suffolk County member, who sports wire-frame glasses and a short, brown ponytail – says they don’t consider what they do charity.

“Charity is the lowest rung of what we do,” he told me. “What we want to do is help people organise themselves – reorganise the conditions of their lives, so they don’t have to depend on someone else for a meal.”

According to Redneck Revolt’s mission statement, organising people also requires organising a defence of their communities. Hence, the gun range.

The Suffolk County branch group meets up for weekly sessions at the range, the name of which they asked to be kept secret. They often bring along other leftists groups, like the PSL, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), or the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Mike says those are some of his favourite days on the range.

“I think it’s very cool that we can bring groups together that normally wouldn’t have anything else in common,” he told me. “And seeing a whole bunch of leftists with guns is cool.”

Not everyone thinks the guns are cool, of course. Redneck Revolt has gotten pushback from liberal groups who think the weapons sully their image. But the members maintain that the firearms are necessary to protect themselves, and the communities of colour they want to help serve.

“We are willing to take on personal risk to defend those in our community who live under the risk of reactionary violence because of their skin colour, gender identity, sexuality, religion, or birth country,” the group’s mission statement reads. “For us, that means that we meet our neighbours face-to-face, and stand alongside them to face threats whenever possible.”

This summer, the Suffolk County branch rallied to the cause of Keenan and Anthony – two young, black men who were killed in a dirt bike crash on a local highway. Witnesses said they saw a 27-year-old white man purposely run over the two bikers with his minivan. The suspect, however, was charged only with one count of reckless endangerment. He pleaded not guilty.

Shortly after the charges were announced, Redneck Revolt joined the Justice for Keenan and Anthony Coalition with the PSL and a local Black Lives Matter chapter. The coalition lobbied the district attorney to upgrade the charges, marching in a protest that momentarily shut down the same highway where the bikers were killed. The charges in the case were upgraded to second-degree manslaughter and criminally negligent homicide last month.

For some, this may be an even more confusing concept than the guns: Why would an anti-capitalist movement of poor, rural white folks dedicate so much time and energy to fighting racism?

George, one of the founding members of the Suffolk County branch, showed me how he would explain the topic to a fellow working-class white person.

“Say it’s a landscaper,” George said. “He’ll blame [his low wages on] Latinx landscapers who are standing outside the 7-Eleven trying to find work. I would say, at the end of the day both guys are trying to support their families. And it’s the employer who’s screwing you by hiring somebody at a lower wage.”

The Redneck Revolt pitch is surprisingly simple: Both poor white people and poor people of colour are actually fighting against the same enemy – the rich.

“With some of the people,” George said, “a light will go off.”

Redneck Revolt is not, of course, the first group of white people to organise on behalf of people of colour. The group pulls inspiration from the Young Patriots Organisation (YPO) – a group of white workers who gathered nearly 60 years ago in Chicago to defend the rights of poor people of all races.

The YPO partnered with the Black Panthers in their fight for economic justice, in what came to be known as the Rainbow Coalition. While the group itself eventually dissolved, modern politicians of colour – from Jesse Jackson to Barack Obama – have used the moniker to describe the population that elected them to office.

But the idea of an armed, leftist group also conjures up a more ominous association: antifa. The little-known phrase – short for anti-fascist – gained attention this summer when dozens of antifa activists arrived in Charlottesville, Virginia to counter-protest a white nationalist rally.

Unlike many counter-protesters, some antifa activists came armed. A few engaged in violence. The back-and-forth between antifa activists and right-wing militias eventually lead President Donald Trump to declare that “both sides” were to blame for the ugly scene at the neo-Nazi rally.

Redneck Revolt members also came to Charlottesville – and they came armed. Their presence at the rally made national news, including a Fox News headline warning: “The Left has gun-toting militias of its own”.

But Redneck Revolt claims it did not come to Charlottesville seeking confrontation. According to a blog post on their website, Redneck Revolt members came to offer protection for the community and show opposition to white supremacy.

Mainstream liberals, the members will tell you, aren’t doing enough of either of those things.

“Any of the groups out now aren’t touching neo-Nazis and stuff,” George told me. “Because they’re either afraid, or they think that you – that [prominent white nationalist] Richard Spencer, maybe his parents weren’t nice to him and he just needs a hug. And that’s not the case at all.”

The better alternative, George explained, is to do what many antifa activists advocate: “If [white supremacists] have rallies, you show up to said rallies and just let them now that s*** is not going to fly.”

But Redneck Revolt does not consider themselves an antifa group. George explained the difference as mainly one of tactics: Antifa are willing to engage in property destruction, cover their faces in “black bloc”, and occasionally punch Nazis on the street.

“We don’t do that,” George said firmly. “We do everything within the law.”

Indeed, if Redneck Revolt is the revolution, then the revolution is decidedly chill. Members of the Suffolk County branch shake off their Sunday mornings at the range with a weekly book club, where they sip home-brewed coffee and discuss radical texts like Caliban and the Witch. The evening is consumed by a planning meeting, where they decide which charitable projects to take on next.

This week’s meeting took place at Kevin’s house – an old horse barn that someone had turned into a one-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment. The tiny space was packed with books, on everything Soviet military strategy to modern nihilism. The walls were strung with old postcards and tea lights, and a fading evening light streamed in through colourful fabric scraps sewn into curtains.

Almost everyone at the meeting had brought beer. Mae, one of the few female members of the group, had also brought Taco Bell, and was eating it on the floor. The group spent half of the meeting just catching up; strong New York accents bouncing off the walls as they cracked jokes about their decidedly un-radical hometown.

“I don’t think you have to have much skill to work at the shooting range,” Mike joked at one point, during a discussion about one of the surly rangers. “You just have to be a dick, and probably pretty racist.”

Everyone laughed.

The Suffolk County branch was founded this April, as an offshoot of a leftist reading group at Stony Brook University. That’s where George found two kindred spirits in his fellow founding members, Kevin and Josh. A lot of the reading group members were Bernie Sanders supporters, George said, but “we read Che [Guevara] and stuff like that”.

The friends knew they wanted to start a leftist organisation on Long Island, and George liked Redneck Revolt for its strong anti-capitalist message. George is a Communist – a belief system he, like Mike, developed from living in poverty his entire life.

“When I was younger, maybe 16 or 17, I thought if you work hard you can do anything, you’ll be successful,” he told me from the kitchen of his in-law’s home. “Now, I work 65 hours a week and I have nothing to show for it. If it wasn’t for my in-laws, I’d be homeless.”

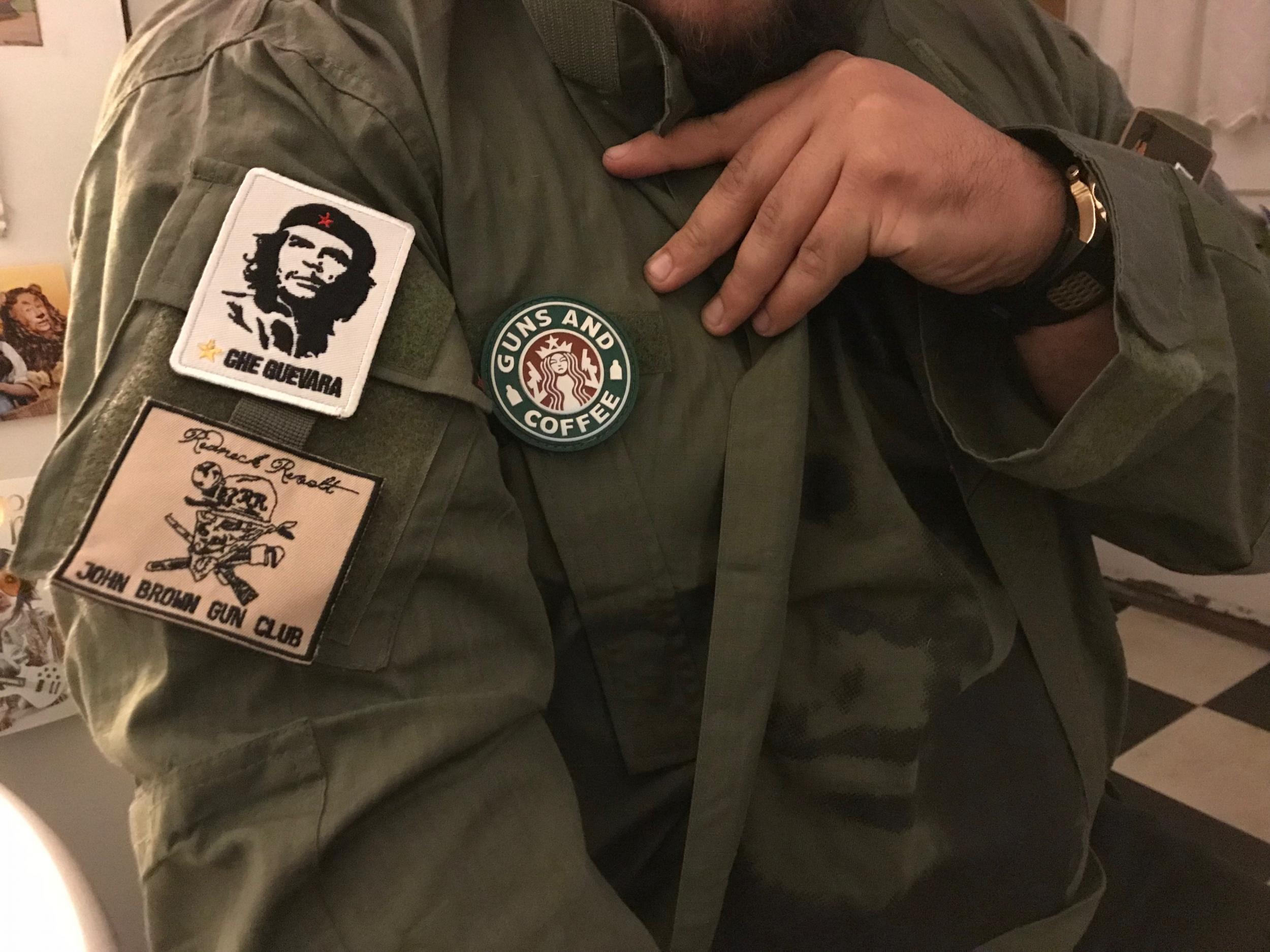

The soft-spoken 30-year-old, who sports “Guns and Coffee” and “AK-47” patches on his coat sleeve, admitted he was also drawn to Redneck Revolt for its emphasis on guns. But he and his fellow group members agreed that now was not the time to broadcast this to the larger community.

“To burst on the scene like gun-toting leftists straight out of the gate would be foolish,” Kevin told me. “The most fundamental thing is healing the community and building up their power.”

The focus of the organisation, Kevin explained, “always comes back to serving the community”. That’s why their first act as a group was to start the community food garden, the yields of which they donated to a local school and the anti-violence organization Food not Bombs.

At that week’s meeting, the group planned how they would give back during the holiday season. They’d already started organising a drive to collect winter coats for the homeless. At this meeting, they decided to hand out the coats themselves, rather than giving them to a charity to distribute.

“Take the charity party out and put the solidarity in!” one member declared.

The room buzzed with the nervous excitement of a new, promising project coming to fruition. Kevin had moved on from beer and was handing out homemade moonshine in wine glasses – the only clean cups left in the house. The group decided it was time to edit their mission statement.

Alex, an applied mathematics student at Stony Brook, played scribe, taking down the group’s suggestions from his perch on the couch. Under the “strategies” section of the mission statement, they agreed to focus on holding town halls, reading groups, and skill shares. They set a goal of working with the disabled population, the homeless population, and opioid crisis victims.

Under the “objectives” section, Mike suggested that too many of their aims were focused on economic issues, rather than social ones. The group agreed. They added “break down all socially restrictive structures” to their to-do list.

At times, the gathering seemed to be as much a support group as it was a planning meeting. The members revelled in talking about their radical ideas, bouncing them off of the few like-minded people who lived on the island.

Before he joined Redneck Revolt, Kevin told me, “I felt isolated because I didn’t know any other real leftists.”

“None of us did,” Mae added.

But the group can also cause friction with the surrounding community. The conservatives on the island don’t like them, of course, but many the liberals also take issue with their tactics. Even the church they volunteer with on Thursday nights doesn’t like hearing about their socialist beliefs or their time on the gun range, George said.

The name Redneck Revolt also rubs some people the wrong way. George described a comment war that ensued on their Facebook page, when a white woman suggested the phrase “redneck” would prevent them from reaching communities of colour.

Other people chimed in, offering their criticisms of the group, until someone wrote: “While you were all fighting over how the name alienates people, Redneck Revolt was at the Riverhead Jail with Black Lives Matter holding a demonstration.”

For emphasis, he added: “You guys are just talking about petty bulls***.”

It seems to be that feeling – that ability to do something meaningful, in a world that feels stacked against you – that keeps members of the Suffolk County branch coming back every week. It may even be what motivates poor, rural white people to keep joining Redneck Revolt branches around the country.

One of the youngest Suffolk County members explained that feeling to me simply. His name was Ben, and he had recently dropped out of college after the cost became too much to bear. He made a living stocking liquor store shelves, and then selling rare silver coins. He joined the Suffolk County Redneck Revolt branch soon after it started.

“The very fact that you’re putting in effort and doing something, rather than sitting at home and maybe writing an angry Facebook post every few weeks – It just makes me feel good about myself,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments