Inside the Puerto Rican town that lays bare the failures of America's relief effort

The Mayor of Loiza has one truck to distribute water. No one has thought to give her a satellite phone. Not a single US soldier has shown up. And residents are being asked to register for assistance online when there is no electricity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The seaside city of Loiza might be Anyplace, Puerto Rico, right now – no power, scant food and drinking water, telephone poles lolling broken on house-tops. Add standing water, mixed with sewage, stewing under the sun. Even the swollen iguanas know something is off with nature.

Strung along the northeastern shoulder of Puerto Rico, it does, however, have something many other communities clamouring for assistance in the wake of last month’s hurricane do not: it’s barely twenty minutes from the international airport in San Juan and therefore the rest of the world. That should make it a first stop of any island-wide effort to distribute emergency aid.

And yet it seems to be no advantage at all. More than two weeks after Hurricane Maria struck, Loiza and its 29,000 inhabitants, many of whom were already living in dire poverty, are still largely on their own. There are no US soldiers handing out bottled water in the town square or keeping order when the sun goes down and you can’t see beyond the toes of your boots.

There is still only one available truck for city officials to attempt to get what supplies they do have – nothing is more urgent than bottled water – to all 44 communities that make up the city. Most astounding of all, nobody has yet thought to give the city’s increasingly desperate mayor, Julia Nozorio Fuentes, a satellite phone. She has no connectivity to the rest of the island. None.

That this is the situation so close to where much of the US aid and manpower is coming into Puerto Rico is a parable of the predicament of the island as a whole. President Donald Trump, who paid a brief visit there on Tuesday, has declared that the emergency response has been going swimmingly. In Loiza, like in so many other places, they beg to differ, obviously.

“The only thing we have seen here were the military helicopters that were flying above us to protect the president when he was here,” Luis Daniel Pizarro, whose job for the town is to coordinate federal programmes, noted sourly. “I think that once people see a military presence or military order on the streets, it will become a little more relaxed.”

The town was entirely cut off for three days after the storm by water. “We became an island within an island,” said Mr Pizarro. That’s in part because several sections of it are below sea level, especially its most impoverished districts. It also sits on the wide estuary of the Rio Grande de Loiza river. Water careening from the mountains and a surge from the ocean converged to create a historic flood. It hardly helped that for nearly a week, the only road to San Juan was buried under thick drifts of orange sand driven by the winds off the beach.

A few things are starting to get better. There are only about 60 people left at the elementary school that became the town’s main emergency shelter when Maria struck, down from nearly two hundred. Some of the floodwaters that inundated thousands of homes have receded.

Yet, in other ways, they may be getting worse. The water that remains is fetid with human waste and a breeding ground for mosquitoes and disease. Those who had money before the storm are running out because the banks are closed and without electricity the cash machines are dead. Social welfare benefits are not coming through. And people are just tired and discouraged.

“Can I speak frankly?” Mr Pizarro asked, guiding The Independent through some of the worst-hit areas. “I am very disappointed. We are fifteen miles from an international airport and we still have almost nothing. The water is not reaching us, it’s not enough. We keep hearing that aid is coming to the ports and the airport and for some reason it is not being distributed fast enough.”

Daisy Calderon is one of those still at the shelter. For the first ten days after the storm she and everyone else had to sleep on the concrete floors of its classrooms. Even camp-beds couldn’t be found. She sees the same problem – food and water may have come to Puerto Rico but bad distribution means it has not come to them. “The situation is horrible,” she said. “They think they are helping but if they are not able to get the help to us than they are not doing their job.”

Ms Calderon, 47, and her family mean to get back to their house soon. But she says everything there has been ruined, including all her clothes. She used to make money doing people’s hair in her kitchen. But without electricity, which won’t be back for months, that’s impossible. Her husband delivers food to schools. But the schools will remain closed for weeks or longer. She said the only money for the family will be the $350 (£266) a month they get in federal food stamps.

“We think it is going to get more serious. People are very destroyed,” warned Mayor Fuentes, whose first floor office in city hall, a modest cement building painted yellow, is besieged every day by residents demanding food and drinking water. At about 5 foot tall, she is almost at her wit’s end. Every night at 8pm she drives to the next big town where the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Fema, has an office just to beg – beg – for more help for her people.

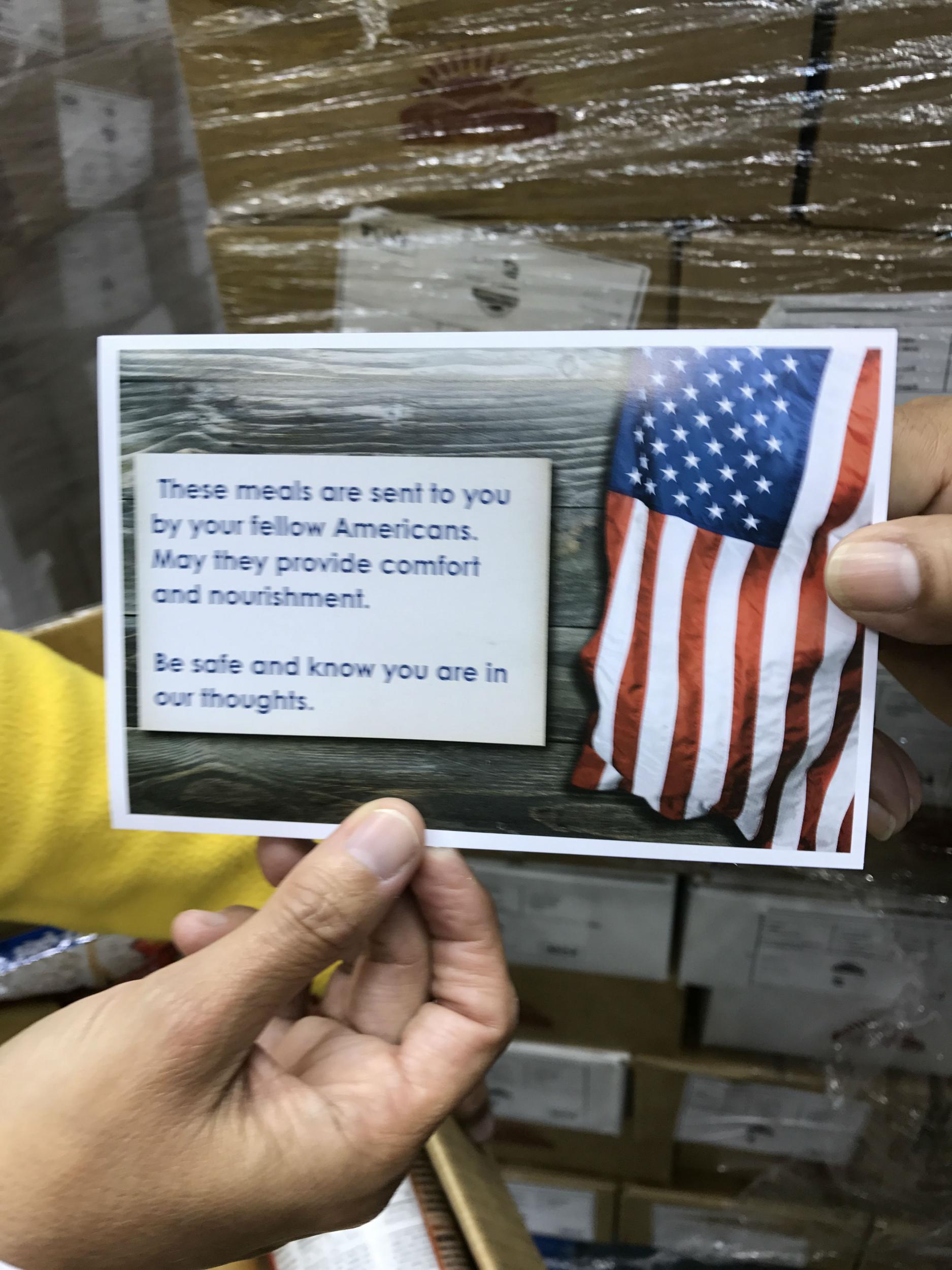

“I think they are trying but the strategy they are using is not the correct one,” she explained. “They have to come to the towns directly. They have to distribute in every town.” Some food boxes have been coming in from Fema, but far too few of them. And according to the mayor what’s inside them – apple sauce, sweet treats, two cans of Italian ravioli – is all wrong. “They don’t want that kind of food. They don’t need snacks. They need rice. People are desperate.”

She needs more trucks and more water. And she needs Fema to understand better that Loiza is not Orlando or Houston. For now, it is asking residents who need help fixing their homes – almost everyone – to apply online, obviously a laughable request. Even if everyone in Loiza was computer literate, there are no computers to register on. And there is no electricity.

Asked what she thought of Mr Trump’s assurance that the relief effort is going well, Mayor Fuentes seemed unsure whether to speak or bite her tongue. “That’s what Donald Trump says, but he didn’t come to Loiza, he went to a town that is rich,” she finally offered, referring to his stop on Tuesday in one of the more prosperous parts of San Juan. “We are poor, very poor.”

Back at the shelter, Melanie Pizanno Quinones, 19, spends most her days trying to keep her 18-month daughter, Kamila, out of trouble and monitoring her sugar levels. Kamila has diabetes. She is grateful to be there – the windows, doors, the roof are all gone from her home – but she too voiced dissatisfaction with the relief effort. “There is not enough food,” she said.

The day we visit, the shelter was filled with rumours about Mr Trump and his visit, prompted, it seemed, by a moment captured by the media of him hurling rolls of kitchen towel into a crowd in San Juan. No one in Loiza had seen the reports, but word had been filtering out.

“They are saying he threw paper towels in the face of the governor,” Ms Quinones said. “That’s what they are saying here. They are saying he is not going to help the people, that he doesn’t like the people here.” She paused and seemed to make up her mind. “Trump is doing nothing. You are throwing paper towels when people here are dying. He is doing nothing to help us.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments