Medellin's falling homicide rate and social investment brings fresh hope to the former murder capital of the world

The once dangerous Colombian city has been transformed into a safe haven thanks to investment in public transport and police operations against the drug cartels

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As Ofelia Sanchez boils black pudding on a makeshift stove outside her hillside home in Medellin, she barely notices the acrid smoke that stings the eyes.

When she arrived in Comuna 13 – a shanty community of 140,000 – in 1995, she and her family had almost nothing, and her sons were soon drawn in to the endemic crime that made it the most dangerous neighbourhood in the city.

“My sons are in jail,” Mrs Sanchez, 56, says. “We didn’t have anything to eat so they got involved with the local gang. “We didn’t have enough to live on but I made great efforts, and now I run a little shop here.”

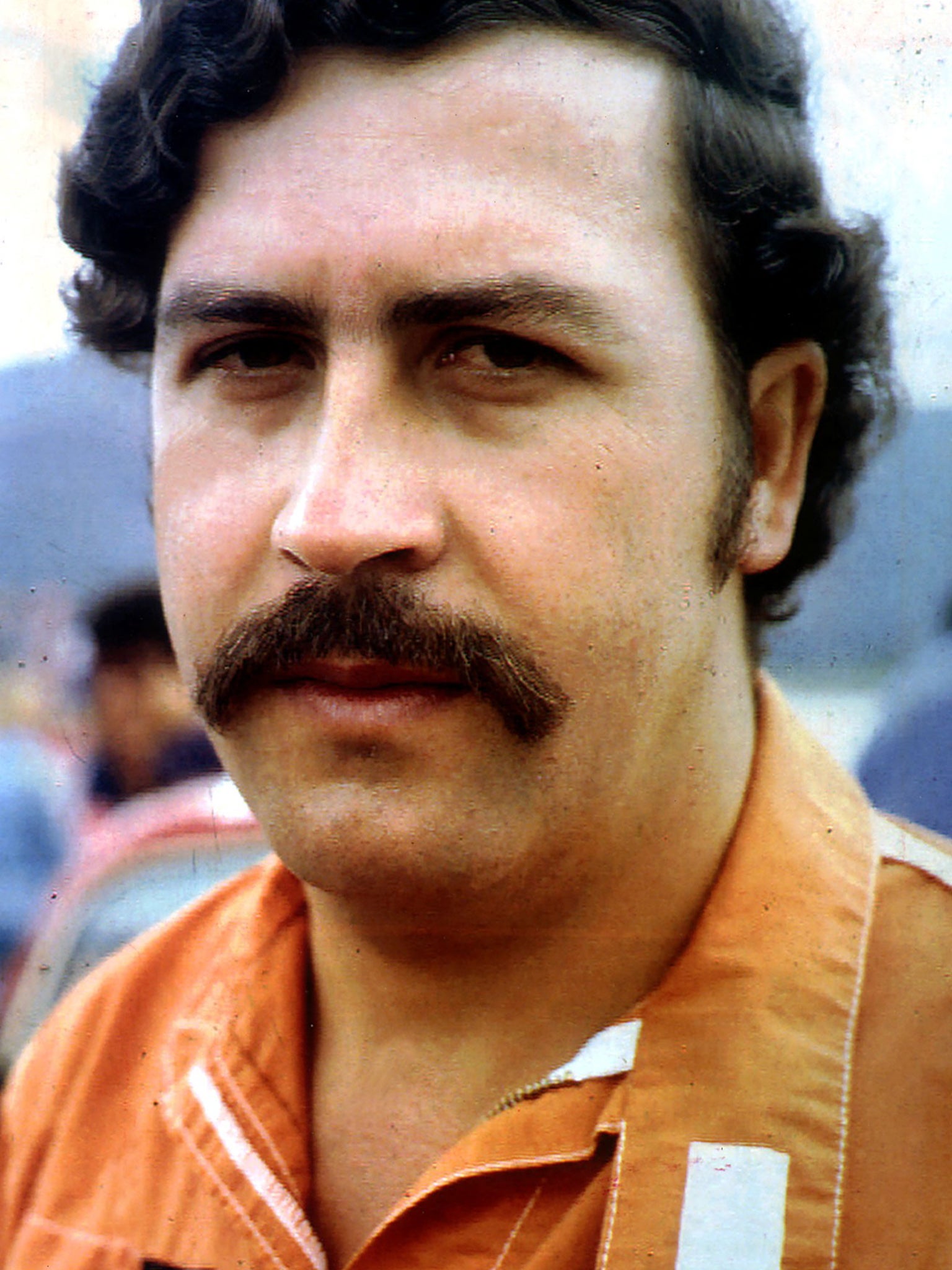

It was only 20 years ago that criminal factions led by powerful drug lords – including the infamous Pablo Escobar – made Medellin the most murderous city in the world, with a homicide rate of 381 per 100,000 inhabitants.

Escobar and Colombia’s notorious cartels drew on the desperation and poverty of families who had been forced from other regions by rebels linked to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), one of a number of groups that has been battling the government in a conflict that has lasted 50 years. In fleeing to Comuna 13, splayed across the lush Andes mountains that frame Medellin, Mrs Sanchez and many others were escaping worse violence elsewhere. “It was horrible,” she said, as she recalled leaving Urabá, 64 miles north of Medellin. “I was forced to move by paramilitaries. I only had the clothes I was wearing.”

After years of conflict, though, Medellin has started to recover. The killing of drug mafia kingpin Escobar in 1993 was followed by investment in public transport, opening up the city to its once terrorised residents. With a new metro system that linked the suburbs, a cable car system that integrated Comuna 13, and outdoor escalators that improved access within the community itself, Medellin was able to reclaim its public spaces.

In 2013, the Urban Land Institute named it Innovative City of the Year, and a recent survey of the most dangerous cities put Medellin at 49th out of 50. Its murder rate fell to 26.8 per 100,000. “We’ve become an example for Colombia,” said Carlos Carmona, 34, who is from Bello, a suburb of Medellin. He said times have changed from when he grew up, hearing gunshots every night.

While Medellin appears to be winning its battles, the country is making progress in peace talks launched in 2012 and brokered in Cuba with Farc leaders - although it is a long and delicate process.

As recently as 2007, Olga Luz Jiminez Vasquez arrived in Comuna 13 after she was displaced by guerrillas and paramilitaries. By then, Medellin had invested heavily in improving safety and public access but rebels were still maintaining their grip elsewhere in the department of Antioquia. “I was forced to move from Campamento where three mayoral candidates were assassinated,” Mrs Vasquez, 49, said. “It’s better here.”

Since February, police have launched their biggest operation since bringing down Escobar to capture the new drugs mafia boss Dairo Antonio Usuga, known as Otoniel. And former president Alvaro Uribe has urged the government not to rush into an agreement with Farc, opposing an amnesty over fears of impunity for the rebel leaders. For all sides, it is clear there is a long way to go.

“There is still much to be done before we can say that almost everything is ready,” said Commander Pablo Catatumbo, a Farc rebel leader, at the International Convention Centre in Havana last month.

But in Medellin, the changes of the past 20 years have been encouraging, bringing fresh hope to the “city of eternal spring”. “I’m not going to say it’s like Switzerland now but it’s changed, you can feel it,” said Mr Carmona. “I can’t say there are no more gangs but at least they are not opposing the government as they know the social investments benefit the whole city.” Mrs Sanchez and her husband Joaquin Emilio Cassas agreed. “We can see the progress,” she said. “We lost our house, our animals but I’m not sad,” Mr Cassas added. “The community is good. We don’t have so much violence. There’s peace here.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments