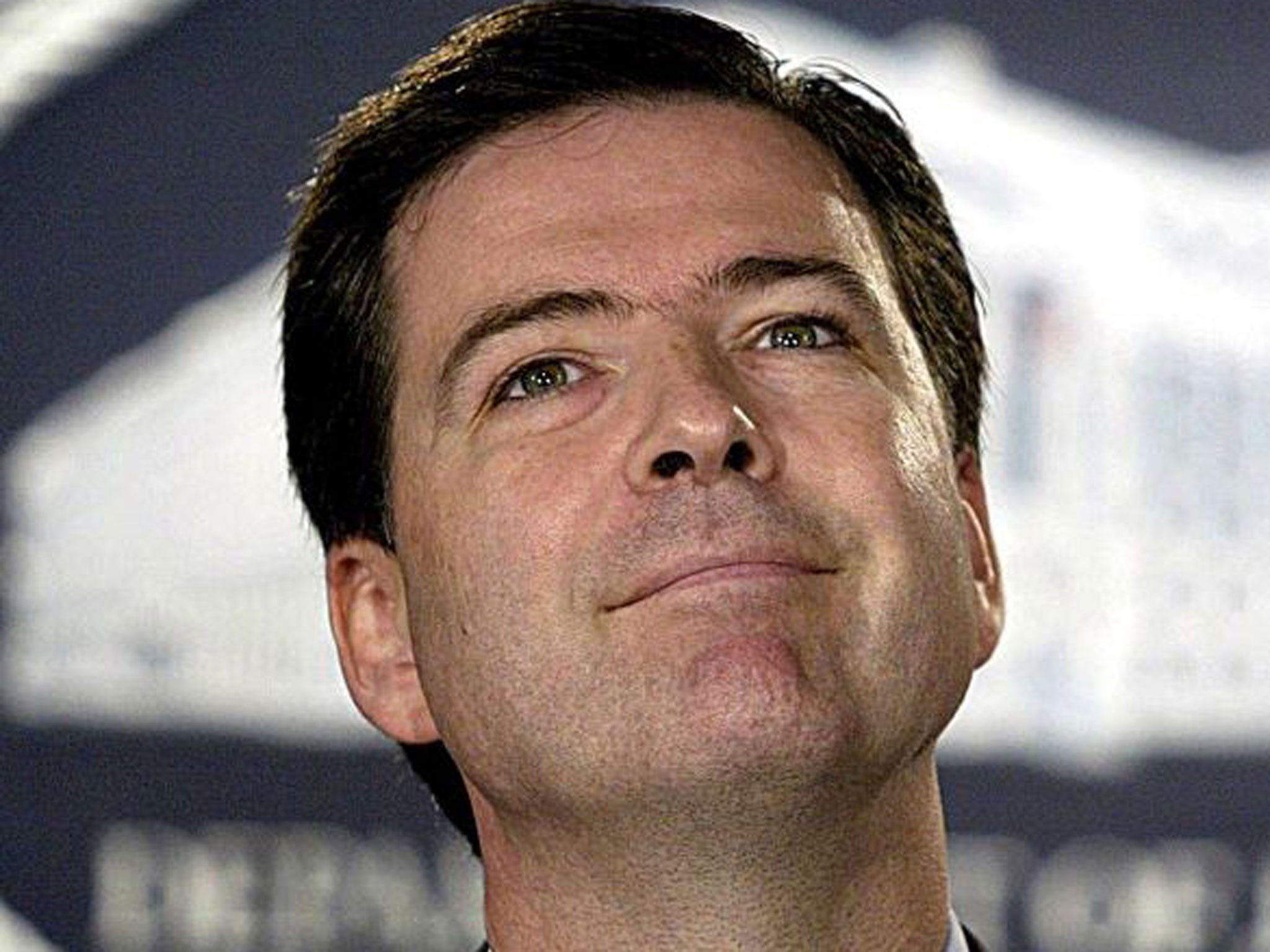

James Comey: The 6ft 8in tall Republican set to lead the FBI

Can he negotiate Washington’s partisan bickering in an era of no money?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.President Barack Obama and the man he wants to lead the FBI have several things in common. The pair are of a near identical age. (Jim Comey is 52; the President hits that mark in August.) The blood of the University of Chicago runs in both men’s veins: Comey took his law degree there; Obama later taught in the university’s law school for a dozen years. Like Obama, Comey apparently fancies himself at basketball. And, not least, both have the same favourite theologian: the Protestant Christian liberal-realist Reinhold Niebuhr.

Obama confessed his admiration for Niebuhr to a columnist a year before his election, and many of his better moments in office have borne that out: a determination to do what is right, tempered by pragmatism and the clear-headed recognition that all humans make mistakes, that evil will always be with us. And so it may be at the FBI for Comey – who even wrote a thesis on the thinker and ethicist widely considered the most important American theologian of the 20th century, stressing Niebuhr’s belief in a Christian’s duty of public service and public action.

But set aside the spiritual stuff. If ever a man had the CV to head the world’s most famous, and certainly most powerful, law enforcement agency, it is Comey. In 1987, two years after graduating, he was hired as a prosecutor by the then US Attorney for the southern district of New York, a certain Rudy Giuliani. The district, which includes Manhattan and Wall Street, is the highest-profile federal jurisdiction in the land, and Comey excelled there, prosecuting several headline-making cases, including the Gambino crime family.

By 1996, he had moved to Richmond, Virginia, where, as assistant federal prosecutor, he cracked down on the city’s then rampant gun crime. And in early 2001, he secured indictments in the long-stalled Khobar Towers case in which 19 American servicemen were killed by a truck bombing near Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, in 1996 – almost certainly an early work of Osama bin Laden and al-Q’aida.

A few months later, Comey was back in New York, by now promoted to Giuliani’s old job. His scalps this time included not only terrorists but also Martha Stewart, America’s one-woman lifestyle industry, for insider trading. Some accused prosecutors of grandstanding, of turning an insignificant event into a show trial. But Comey would have none of it. “This criminal case is about lying,” he said of Stewart, “lying to the FBI, lying to the SEC [Securities and Exchange Commission], lying to investors.” In 2004, Stewart was convicted and given a five-month jail sentence. Comey, though, had long since moved on to higher things, summoned by George W Bush in 2003 to Washington as deputy attorney general, the second ranking law officer in the land.

In practice, the job is at least as taxing as that of attorney general itself. The deputy oversees the day-to-day management of the Justice Department, which includes the FBI and federal prosecutors across the country. Inevitably it is hugely political as well – as Comey found out in a few quite extraordinary days in 2004.

The “war on terror” was at its height, and the Bush administration was seeking a required stamp of approval from the attorney general for a top-secret programme of warrant-less wiretapping within the US. Comey and his boss John Ashcroft might have been Republican appointments. But both believed the programme was illegal, as did Robert Mueller, the FBI director of the day whom Comey, if nominated and confirmed by the Senate, would now succeed.

As a rule, bureaucratic Washington, a largely one-industry town populated by brainy, self‑important but frequently tedious overachievers, is a far cry from the many Hollywood movies set there. Not, however, on the night of 10 March 2004. Ashcroft had just been rushed to hospital for emergency gall bladder surgery and was in an intensive care unit, when Comey was tipped off that Bush’s chief of staff and legal counsel were on their way to secure authorisation from an ailing, scarcely conscious attorney general to extend the wiretapping programme.

Alerting Mueller, Comey rushed to the hospital to pre-empt the move. The FBI director, meanwhile, gave personal orders to FBI agents that under no circumstances was Comey to be removed from Ashcroft’s room. The two White House officials arrived, only to retreat after Ashcroft, who somehow rose from his sickbed, and Comey confirmed their refusal. Both of them, as well as Mueller, had resignation letters prepared, if the Bush White House did not relent. In the end it did relent, and a scriptwriter’s dream that might have surpassed even Watergate’s “Saturday Night Massacre” was avoided.

As details of the confrontation emerged, the episode conferred hero status on Comey among Democrats. As a federal prosecutor, his politics had been vague, but it was generally assumed he was a standard law-and-order Bush loyalist. Now he was a Republican dissident, an anti-Cheney who dared to say no to his masters in the nobler cause of defending the integrity of the Justice Department, indeed of the constitution itself.

Even so, most Republicans too still liked him. Comey’s height, 6ft 8in, might have made him an intimidating figure, but who could dislike for long so gregarious a man, with a terrific sense of humour? And no one begrudged him when he left Washington to return to the private sector, as chief counsel first for Lockheed-Martin, then for the Bridgewater hedge fund. After all, when you’ve five children to put through college, a government salary doesn’t go very far.

But if and when Comey faces the Senate Judiciary Committee for confirmation, the hedge fund issue could return to haunt him. Republicans are furious at Obama’s perceived hostility to Wall Street: as FBI director, Comey could be in charge of investigating former colleagues. Assume, however, that he is nominated and confirmed. The FBI he would inherit would be both familiar, yet very different.

The shade of J Edgar Hoover has long since been banished, and the mission of the agency that Hoover invented and ran for decades almost as a state within a state has been transformed since 9/11. Once the priorities were organised crime – the mob, racketeering, kidnappings – and white-collar fraud. Now counter-terrorism is the prime focus. These days, the bureau is less Scotland Yard, more Special Branch and MI5. Rocky relations with the CIA, a big factor in the failure to thwart the September 2001 plot, appear to have improved. Even the FBI’s notoriously antiquated computer system has had a massive upgrade.

But if Comey does replace Mueller, who took over the bureau just a week before the attacks, the sense of continuity may be even more striking. Their careers have been similar. Both were stand-out federal prosecutors and both served as deputy attorney general (albeit in Mueller’s case briefly, and in an acting capacity only, early in George W Bush’s administration). The outgoing director was Comey’s friend and mentor during the latter’s first stint in Washington – a friendship surely sealed on that remarkable March 2004 night. Mueller’s tenure, during which he shunned the limelight and ran the bureau as the straight-arrow prosecutor has been judged a success; so much so, indeed, that Congress in the summer of 2011 agreed with rare unanimity to bend the rules and grant him a two-year extension when his mandatory 10-year term expired.

The one blot has come at the end, with the revelation that the FBI did not follow up on earlier warnings about Tamerlan Tsarnaev, the elder of the brothers who bombed the Boston Marathon. Until then, however, and contrary to every foreboding, the US had not suffered a significant attack on its soil since 9/11. And even Boston was home grown, the hardest form of terrorism to prevent – at least in the free and law-governed society that Jim Comey fervently believes the US must remain.

A Life In Brief

Born: James Brien Comey, Jr., 14 December 1960, Yonkers, New York.

Family: Son of James Brien Comey, Snr, who works in corporate real estate. His mother is a homemaker and computer consultant. He has a wife, Patrice; they have five children.

Education: Northern Highlands Regional High School in Allendale, New Jersey, then chemistry and religion at the College of William and Mary. Received his JD from the University of Chicago Law School.

Career: Served as a law clerk for United States district judge John M Walker, 1985- 1987. Served in US Attorney’s Office for the southern district of New York as the deputy chief of the criminal division, 1987-1993. Managing assistant for the Richmond division of the US Attorney for the eastern district of Virginia, 1996-2001. Deputy attorney general under George W Bush, 2003-2005. General counsel and senior vice-president of Lockheed Martin, 2005-2010. He is the senior research scholar and Hertog fellow on national security law at Columbia University and is on the board of HSBC Holdings in London. Nominated by Barack Obama in May as director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

He says: “Doubt at a high level of government is seen as weakness. And I thought doubt is strength. The wisest people I work with make decisions knowing they could be wrong.”

They say: “The integrity of Comey is pretty much unmatched with the exception of Director Mueller.” Tim Murphy, former deputy director of the FBI.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments