Gun killings fell by 40% after Connecticut passed this law – so why are other US states not following its lead?

Despite criticism when it was launched, researchers now say that Connecticut's 'permit-to-purchase' law was actually a huge success for public safety

In the early '90s, gang shootings gripped Connecticut. Bystanders, including a 7-year-old girl, were getting gunned down in drive-bys. "The state is becoming a shooting gallery, and the public wants action," an editorial in the Hartford Courant said at the time.

So in the summer of 1994, lawmakers hustled through a gun control bill in a special session. They hoped to curb shootings by requiring people to get a purchasing licence before buying a handgun. The state would issue these permits to people who passed a background check and a gun safety training course.

At the time, private citizens could freely buy and sell guns secondhand, even to those with criminal records. Connecticut’s law sought to regulate that market. Even private handgun sales would have to be reported to the state, and buyers would need to have a permit.

Critics scoffed at the plan. They argued that a permit system would hassle lawful citizens, while crooks would still get guns on the black market. If the problem was criminals with guns, why not clean up crime instead of restricting guns?

"This will not take one gun out of the hands of a single criminal," State Rep Richard Belden complained to the New York Times in 1994.

Even some supporters of the law, which took effect in 1995, called it a "small step" — a gesture to placate residents alarmed at the gun violence.

Now, two decades later, researchers at Johns Hopkins University and the University of California, Berkeley, say that Connecticut’s "permit-to-purchase" law was actually a huge success for public safety.

In a study released on Thursday in the American Journal of Public Health, they estimate that the law reduced gun homicides by 40 per cent between 1996 and 2005. That’s 296 lives saved in 10 years.

How they analyzed the data

Of course, there’s no way to measure the true impact of Connecticut’s "permit-to-purchase" law. We can’t access the alternate universe where Connecticut’s law never existed. But we can compare Connecticut against the 39 states that didn’t have similar legislation at the time.

That’s what the researchers did, using records on gun killings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

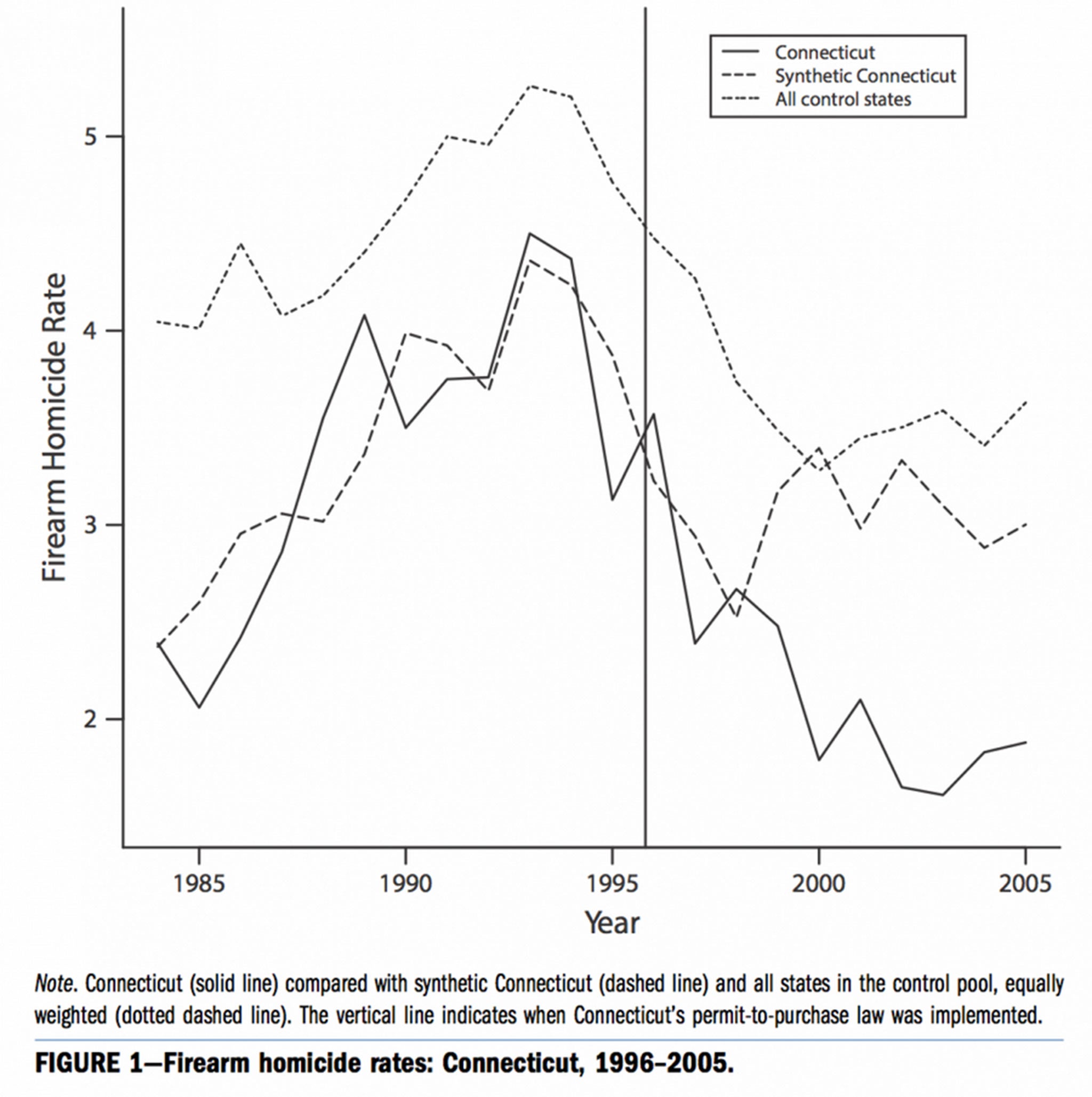

In the control states, homicide rates tumbled in the mid '90s — but in Connecticut, the gun homicide rate fell faster and farther, even after controlling for demographic changes, incomes and policing levels. This is a sign that Connecticut’s gun policy was having an effect.

To arrive at a more precise estimate, the researchers tried to predict what Connecticut would have looked like without its “permit-to-purchase” law. Taking data from statistically similar states, they made a "synthetic" Connecticut — a Frankensteinian creation that is mostly Rhode Island, with some Maryland, and traces of California, Nevada and New Hampshire.

Synthetic Connecticut and real Connecticut look the same before 1996. But they diverge soon after Connecticut’s law kicks in. In the end, there is a 40 percent gap between synthetic Connecticut and real Connecticut — between the expected number of gun-related homicides and the actual number of gun-related homicides.

The researchers give credit for that difference — 296 lives — to the protective effect of Connecticut’s permit-to-purchase law.

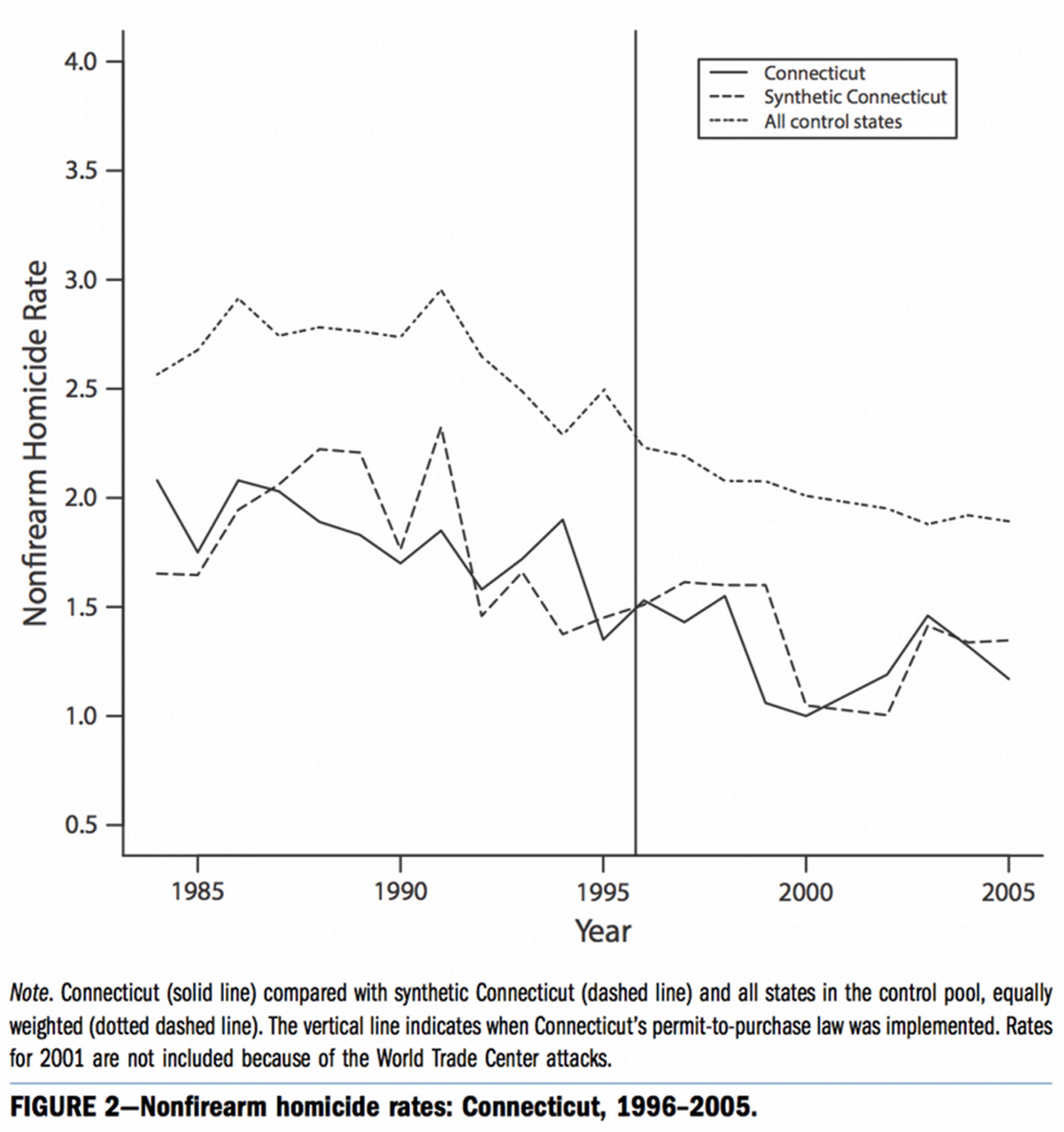

In contrast, Connecticut’s law did not seem to have any effect on non-gun homicides. Synthetic Connecticut and actual Connecticut look the same before and after 1996 — which makes sense, because gun control laws should only affect gun-related killings. This helps rule out alternate explanations. The peculiar decline in Connecticut’s gun homicide rate wasn’t the side effect of some overall decrease in murders after 1996:

How do permit-to-purchase laws work?

Federal law requires gun dealers to run background checks before selling to anyone. But it doesn’t require background checks for gun sales between private citizens. This is called the “private sale” or "gun show" loophole.

In other words, most states will let you buy a gun off a stranger on Craigslist, no background check needed.

Permit-to-purchase laws, which are on the books in 10 states, pose one way to tame the secondhand market. These laws require people to get pre-cleared by state or local authorities, who issue them a permit allowing them to buy a gun. Connecticut, for instance, requires permit applicants to pass a background check as well as a gun safety training course.

Permit-to-purchase laws make it a crime for anyone to sell or give a gun to someone without a permit. They discourage people from selling guns to criminals, who wouldn’t clear the background check for a permit.

Critics of these laws say they won’t keep guns out of the hands of criminals, because, well, criminals won’t follow the law.

That’s flawed thinking, says Daniel Webster, one of the authors on the study and director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research.

Connecticut’s gun permit law made it harder for guns to enter the black market. Lower supply means higher prices. A motivated crook could still get her hands on a gun, but it would take more time and resources. Perhaps she would have to travel to a different state, or ask a friend with a clean record to illegally obtain a gun for her.

"People assume incorrectly that criminals will do anything and everything in terms of cost and risk to get their hands on a gun," he said. "But that simply is not what the data tells us." Connecticut’s law didn’t stop criminals from acquiring guns, but it deterred enough of them that the gun homicide rate dropped.

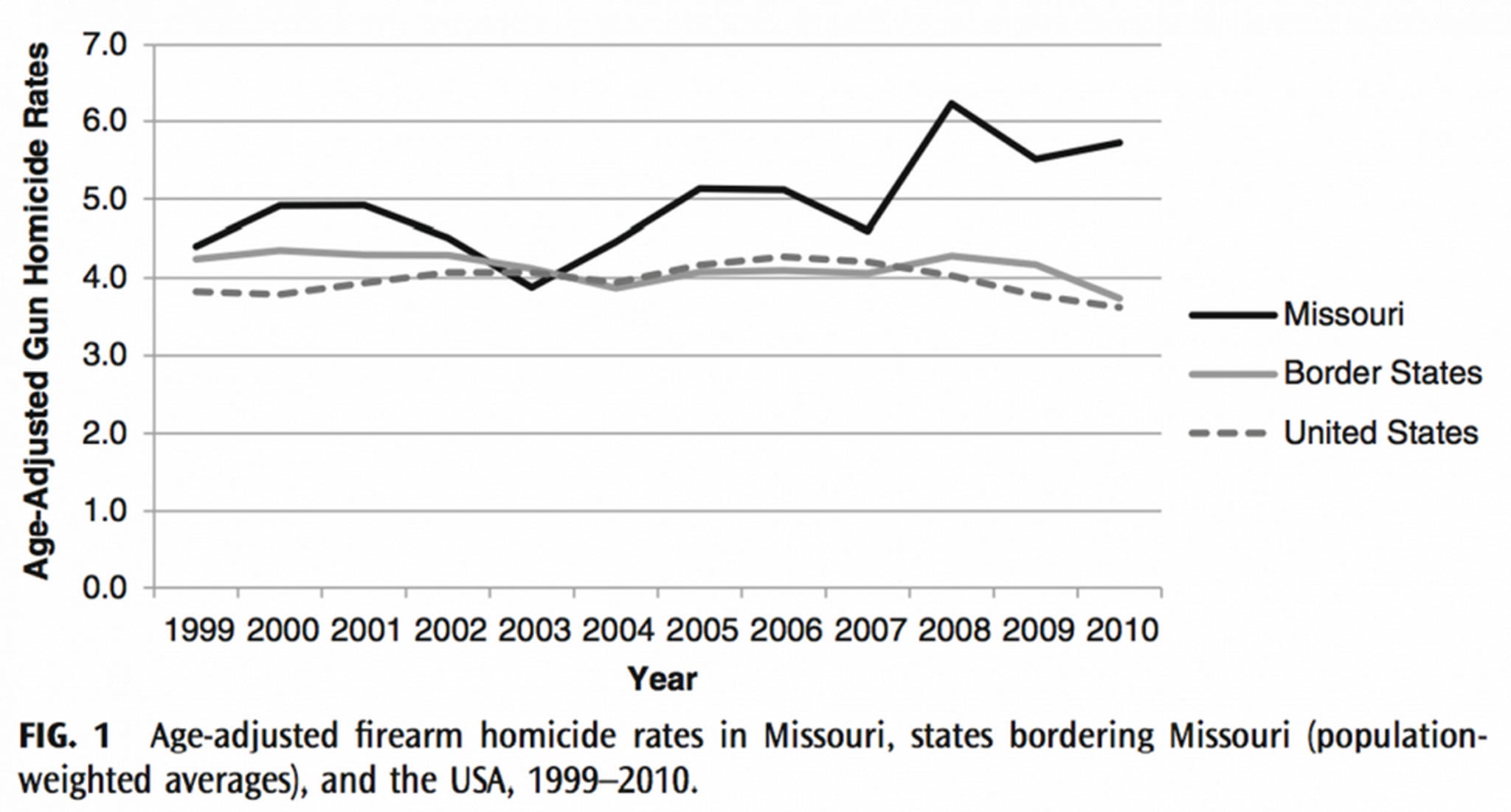

Last year, Webster and some colleagues documented the mirror-opposite effect in Missouri, which repealed its permit-to-purchase law in 2007. Soon after, police in Missouri, Illinois and Iowa were coming across more Missouri guns at crime scenes. The gun-related homicide rate in Missouri also went up. In a paper published in the Journal of Urban Health, the researchers argue that the repeal of the law was responsible for 50 additional gun deaths in Missouri per year, a 23 percent increase.

Together, these two reports offer compelling (if somewhat indirect) evidence that permit-to-purchase laws help save lives, probably by keeping guns off the black market.

An overwhelming number of Americans say that they favor universal background checks — that is, they want anyone who obtains a gun to pass a background check first. Gun-rights activists retort that these restrictions only impede the lawful ownership of guns. But that’s clearly an exaggeration. When laws make it harder for people to sell guns to criminals, well, criminals will have a harder time finding guns.

Here is the classic tradeoff between liberty and safety. Private citizens are giving up the freedom to sell a gun to whomever they want. They are also giving up the convenience of buying a gun without a lot of waiting and paperwork. Are these annoyances worth it? That depends on how many lives you think are saved by keeping guns out of criminal hands.

It’s a number we can only guess at. So far, the best estimate seems to be: a lot.

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments