Friendship Nine's civil rights-era convictions overturned by South Carolina court

The men were the first to choose prison over fines for ignoring a segregation order and sitting at a whites-only lunch counter

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

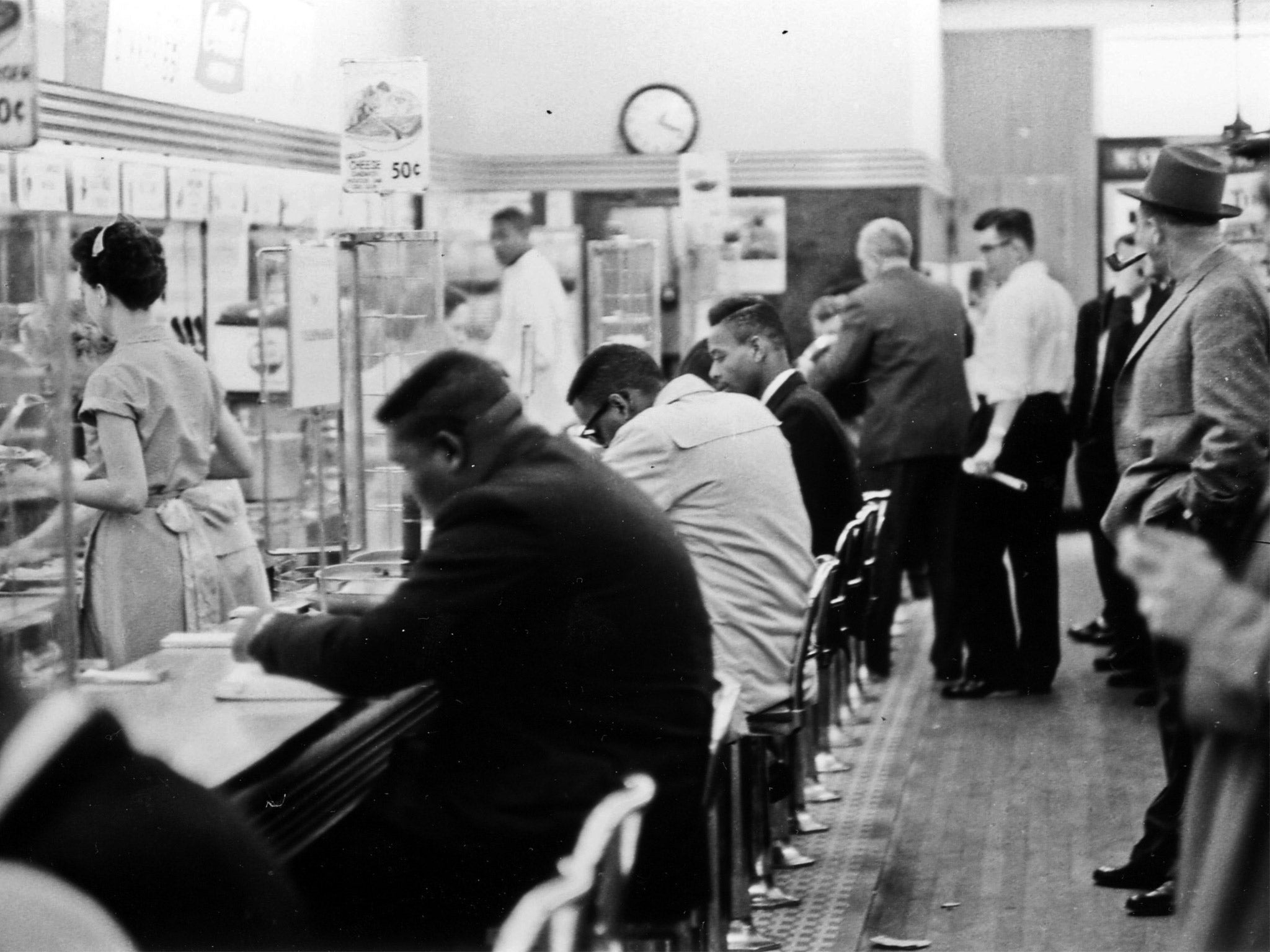

Your support makes all the difference.It will be 54 years ago on Saturday when the ‘Friendship Nine’ walked into McCrory’s in Rock Hill, South Carolina, and took their seats at its whites-only lunch counter only to be arrested, convicted of ignoring a segregation order and thereafter sent to serve thirty days on the county prison farm.

Criminals, however, they are no longer. In an emotional session in Rock Hill’s courthouse early today the convictions of all nine men, so named because most of them attended the now shuttered Friendship College, were overturned and each man was legally absolved.

The sit-in on 31 January 1961 is still remembered as having given inspiration to non-violent protests that were to follow all across the South as the civil rights struggle raged in the early Sixties. The nine young men were the first in the movement to choose incarceration for their alleged crimes over fines.

The survivors among the Nine came to court and listened as their convictions were rolled back by Judge Charles Hayes, the nephew of the judge who presided over their original trials. The court house itself is not far where McCrory’s used to be. And their lawyer today was the same man who defended them back then, Ernset Finny Jr, who was to rise to become the Chief Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court.

“We cannot rewrite history,” Judge Hayes, told the court, “but we can right history”.

The motion to have the convictions reversed was first made by local prosecutor Kevin Brackett. “There is only one reason these men were arrested... and that is because they were black,” he noted. “It was wrong then, it’s wrong today.”

Among the men who is still living and who attended the session is Clarence Graham, 72. He said that neither he nor his friends had been out for “hero worship” either in 1961 or indeed now in spite of the renewed media spotlight on the case. “It wasn’t for any glory,” he said. “We were simply... students who were tired of the status quo, tired of being treated as second-class citizens.”

He said the case offered a lesson to those still fighting for equality in America. “Even though we were treated unjustly, still non-violence prevailed. You think we’re going to sit down and rest now? No, no, no. We’ve got to lead by example.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments