Falkands: Departure of Argentina's President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner could signal thawing of relations with UK

Poll fuels hope of less combative stance with UK

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Eduardo Ochoa was 19 when he was deployed to Patagonia in Argentina in case the Falklands War spread to the mainland. More than three decades later he is a stalwart at a protest camp in the historic Plaza de Mayo, demanding recognition – and benefits – for his service. It’s seems a forlorn cause and the protesters hopes of success have become as tattered as their banners and ragged, flapping tent.

Yet he, like many others here, harbours hopes of a different kind – that the imminent departure of President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner from the nearby pink palace, or Casa Rosada, will help end the cantankerous sparring between Argentina and Britain and allow them to make progress towards solving the seemingly endless dispute over the future of the South Atlantic archipelago. “Here the politicians all know they have talked to England in the wrong way for the past many years,” he said.

“They pretend that it’s good politics, but underneath they all know it’s the wrong approach. They need to find a new way to deliver advantages for both sides. We can settle this.”

In her eight years in office, Ms Kirchner has consistently baited Britain over the disputed islands, including the day she ambushed the Prime Minister David Cameron at the United Nations and thrust a letter into his hand demanding the start of status negotiations.

What happens now will depend in part on the outcome of the presidential election. The only non-Peronist contender, Mauricio Macri, has already pledged to turn down the rhetoric and symbolically abolish the junior minister position in the foreign ministry that exists purely to pursue Argentina’s goal of reclaiming the islands, known in the country as Las Malvinas.

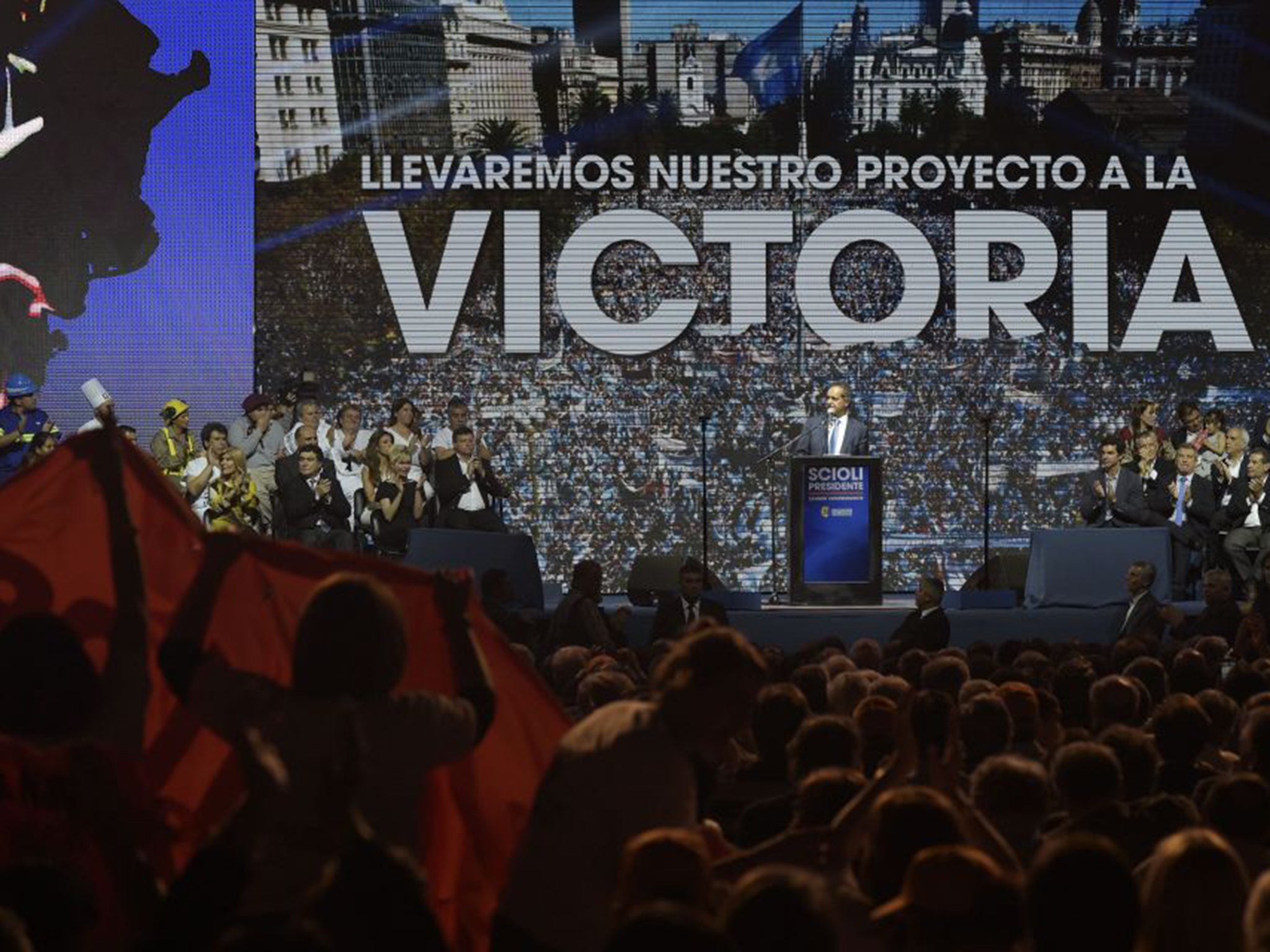

Polls suggest, however, that it is Ms Kirchner’s preferred choice, Daniel Scioli, who will prevail, if not today then in a run-off with Mr Macri in November. He, like Ms Kirchner, is of the populist, Peronist movement. Yet there is widespread expectation that he too would seek to adopt a fresh and less belligerent tone in the hope of bringing Britain to the table.

“I think he [Mr Scioli] will try to put all this nationalistic posturing and discourse in a new perspective,” Marcos Novaro, the director of a Cipol, a political think tank in Buenos Aires, suggested. “There is a strong sense of frustration with the hard policies” of Ms Kirchner. “Everyone has the sensation that Argentina gets into these quarrels for no reason ... and that’s true with the Malvinas.”

Ms Kirchner – who cannot run this time, having served two consecutive terms – certainly gained a reputation for her combative style. It was this that led to a stand-off with US hedge funds that own tens of billions of pounds in loans on which Argentina defaulted in 2001. Ms Kirchner labelled the funds “vultures” and has refused to compromise. Whether to negotiate on the loans will be a key issue for the new leader, as will the economy, with inflation around 25 per cent.

With Mr Scioli the continunity candidate, it is believed he may have more luck getting such economic changes through the country’s Congress, but any attempt to reach an accord over the Falklands, especially one short of full sovereignty, would be a tough sell with Congress and with voters. But the door may just be open a crack, Mr Novaro said. “It’s possible a new government with little effort can show that if you ... don’t offend, and don’t insult, Argentina can take the right direction and everyone will applaud him.”

Ernesto Justo Lopez, a retired ambassador to Guatemala and Haiti, and chief of staff at the defence ministry a decade ago, has a slightly different perspective on Ms Kirchner’s record on the islands, arguing that her aggressive stance has been successful at least in terms of garnering support for the cause from neighbours in Latin America and the Caribbean and from delegates at the Special Committee for Decolonization at the UN.

“This has been very important for us,” said Mr Lopez, who spends part of each Friday chewing the cud with other former diplomats at the Café con Peron in downtown Buenos Aires under the gaze of a life-size figure of former President Juan Domingo Peron himself. And while he agrees that Mr Scioli as president might seek a less cantankerous approach with London, he isn’t certain how much it will help.

“Do you think there will be results because of changed manners, or will it come again to substance?” he asks. “Maybe Scioli’s approach will be gentler, but the issue at heart has to do with content. Great Britain defends the principle of self-determination [for the population of the islands] and we defend the principle of territorial integrity… it’s difficult for us to agree.”

Enrique del Percio, a professor at a local Jesuit university, recalls that the Malvinas issue is the only one that unites all Argentines. It even brings warring football fans together when they break into Malvinas songs, especially the one where they all jump up and down and cry: “Whoever doesn’t jump is an Englishman!”

Regaining the islands was included as a national goal in the last constitutional reforms of 20 years ago.

It is a third member at the table, Luis Tibiletti, who served as Homeland Security Secretary under Nestor Kirchner, the late former president and husband of Ms Kirchner, who suggests one “very crucial” new factor has not come into consideration: the election as Labour Party leader of Jeremy Corbyn, who, he knows, has been less than clear on whether he would have sent troops to defend the islands in the 1982 war.

“Cristina is leaving so maybe the Argentine manners will change and maybe with the arrival of Mr Corbyn ... the manners of British Prime Ministers will change also,” he offers with a twinkle that suggests he knows that this may be grasping at straws.

He recalls that before the war, relations between Argentines and island residents were mostly cordial and that for years London and Buenos Aires had wrestled with compromise proposals, including one that envisioned a kind of shared sovereignty and so-called “double flagging”.

“It is not impossible to resolve this,” Mr Lopez suggests, inciting vigorous nods around the table. Not impossible, but difficult.

“If the politicians want it, they can make it happen,” Mr Ochoa back at the protest camp insists. “But they are not talking right now.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments