Death row: The man sentenced 20 years ago... who still doesn't know the day he will die

An execution date for Keith Doolin has never been set, and two decades after his trial, he is still going through the state’s interminable capital appeals system

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

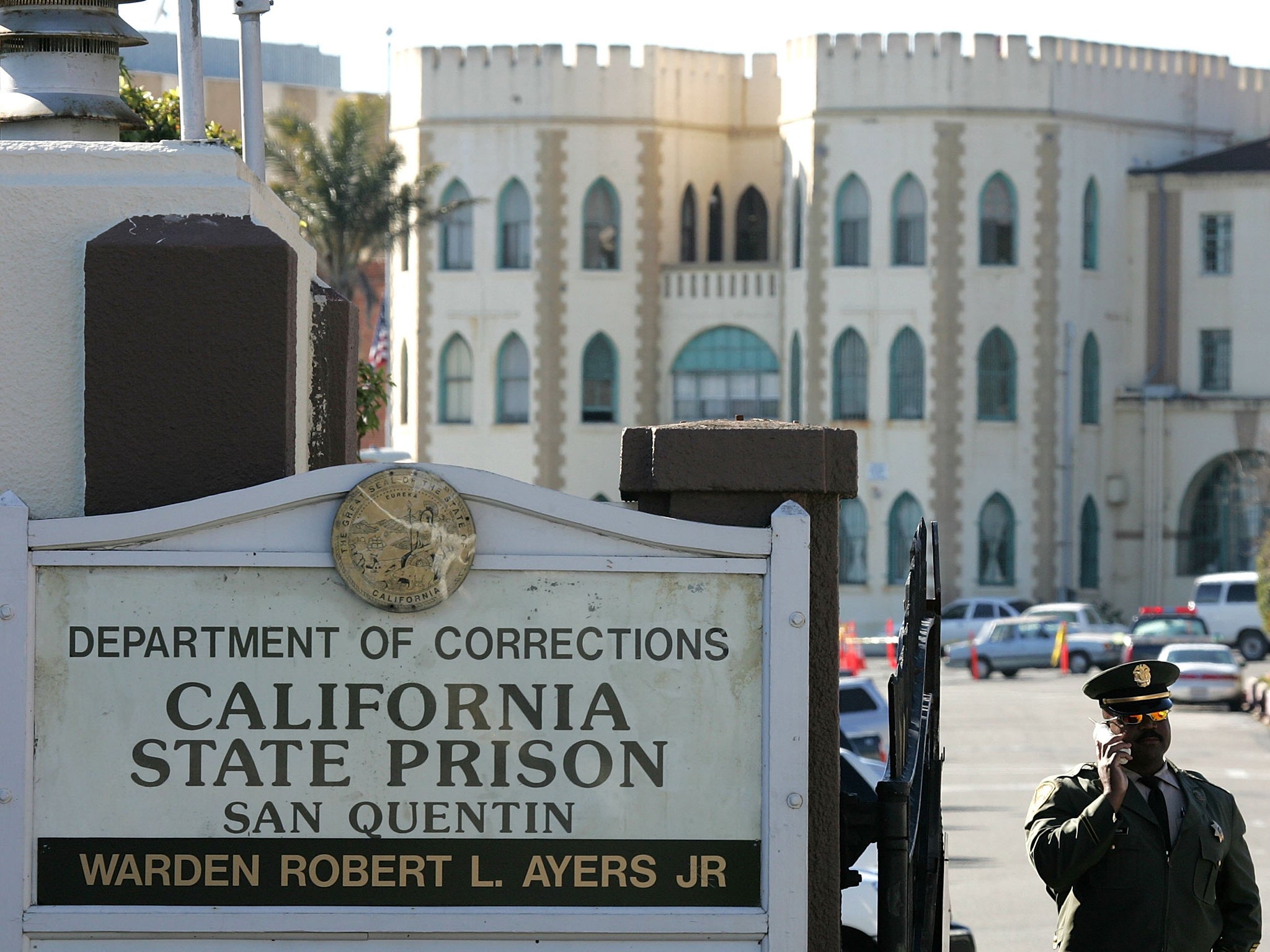

Your support makes all the difference.Keith Doolin lives on death row at San Quentin state prison in California, around 20 miles north of San Francisco. Since his conviction for the murders of two women in 1995, when he was 22, he has spent most of his time in a cell measuring six feet by nine, with a slot window too high in the wall to see out. He sleeps on a thin mattress on the hard floor. Three times a week, he is permitted to spend a few hours in the prison yard with other inmates.

An execution date has never been set, and two decades after his trial Mr Doolin is still going through the state’s interminable capital appeals system. He is far from alone in limbo: California’s death row, the longest in the US, is only going to get longer. Last week, Governor Jerry Brown asked lawmakers for $3.2m (£2.2m) to provide up to 100 more cells for death row inmates at San Quentin.

Since 1978, California has sentenced more than 900 people to death, but executed just 13. In the nine years since the last execution, 49 inmates have escaped death row not via the appeals process, but by dying of natural causes, overdoses or suicide before the state could kill them.

In the Golden State, being sentenced to death in fact means facing a long life of grim uncertainty, not only for inmates, but for their families. “When you have a loved one in prison, that’s a prison sentence for the family,” said Mr Doolin’s mother, Donna Larsen, who is still fighting to prove her son’s innocence. “The death sentence is a death sentence for the family.”

California has more than 750 inmates on death row, up from 646 in 2006, when it last executed a prisoner. The nation’s second-longest death row is in Florida, with just over 400 inmates. There are 20 condemned women at the Central California Women’s Facility near Fresno, and as many as 731 men at San Quentin, housed separately from their fellow prisoners in three dedicated cell-blocks capable of accommodating no more than 715 at a time.

According to the Los Angeles Times, those cells housed 708 inmates last week, with the remainder at court hearings, medical facilities or in out-of-state prisons. In its funding request, the governor’s office described the cell shortage as “critical”, adding that, should the expansion plan be delayed, “San Quentin would not have beds to accommodate the condemned.”

California is one of 32 US states that still has the death penalty, but executions here were halted following a 2006 court ruling, which forbade the state from using its three-drug lethal-injection method. So far, the California authorities have failed to agree on an alternative.

At the ballot box in 2012, 52 per cent of California voters decided in favour of keeping capital punishment. Last year, however, a federal judge ruled that the state’s death penalty was unconstitutional due to its costly and dysfunctional appellate process, which leaves death row inmates waiting for decades to learn their ultimate fate: a delay the judge called cruel and unusual. The office of California’s Attorney General has challenged the ruling; if it is upheld by an appeals court, the case could find its way to the US Supreme Court.

The wife of death row inmate Jarvis Masters, who received a death sentence 25 years ago for a murder he and his lawyers still insist he took no part in, compared the mental anguish of having a loved one on death row to having a child diagnosed with a terminal illness.

“You wait, knowing that sometime in the near future your child is going to die,” said Mr Masters’ wife, who preferred not to be named. “Time goes by, and then the doctors come back and say, ‘Maybe the child’s not going to die. We’re going to do some research and get back to you.’ Meanwhile, your child is still on their deathbed and you’re stuck in limbo. It goes on and on, year after year, and your whole life is on hold without any sense of closure for anyone involved.”

Texas, the most prolific death penalty state, has executed more than 160 prisoners since 2006, and since 2012 has used a single drug, pentobarbital, in its lethal injections. “California can and should have done the same thing,” said Kent Scheidegger, legal director of the California-based Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, who supports capital punishment. He added: “The number of people leaving death row would be greater than the number coming in, if Governor Brown had done what he should have done and got it working again.”

The funding requested by the governor would be used to accommodate the estimated 20 new death row inmates expected per year. Death row prisoners are typically kept in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day, in units that require additional staff and security, making each prisoner significantly more expensive to house than an inmate in the prison’s general population.

“The death penalty costs California an enormous amount,” said Robert Dunham, Executive Director of the Death Penalty Information Centre. “That amount only increases as people continue to be sentenced to death, and the state remains unable to provide them with representation in the appeals process. Those costs would disappear if the death penalty disappeared.”

The interminable wait for an execution that may never occur is bad not only for inmates, but also for their victims and their victims’ loved ones, Mr Dunham said. “What crime victims don’t need is re-traumatisation. And they don’t need false assurances of finality that do not come to pass.”

In 1981, Aba Gayle’s daughter Catherine Blount was murdered by Douglas Mickey, who has spent more than 30 years on death row for the crime. When he was first convicted, Ms Gayle said, she was full of anger and thoughts of revenge. But eventually she exchanged letters with her daughter’s killer, visited him at San Quentin, and changed her mind.

“It took me 12 years to get to the point where I could forgive him,” she said. “I didn’t want to live with those horrible, negative feelings any longer. It has really changed my life, but I would have missed that opportunity had he been executed.”

Now 81 and a passionate anti-death penalty campaigner, Ms Gayle and her family intend to plead for clemency on Mr Mickey’s behalf if an execution date is ever set. “There’s a moratorium on executions, capital punishment has been declared unconstitutional, and yet district attorneys keep seeking the death penalty and sending more people to death row. It’s crazy,” Ms Gayle said. “I have now met many of the wives and mothers of death row inmates, and it doesn’t take long to figure out that there are a lot of victims in this. it’s not just the family of the murdered person.”

Even supporters of capital punishment admit that no death penalty at all would be better than the death sentence indefinitely deferred. “If I really believed that the situation in California could never be fixed, then I would probably be in favour of getting rid of [capital punishment],” Mr Scheidegger said. “But it is entirely fixable.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments