Cheap rivets blamed for massive loss of life as 'Titanic' sank

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Titanic might have gone down more slowly and more of its passengers could have been rescued if the shipyard that built it, Harland & Wolff in Northern Ireland, had not skimped on the quality of the rivets holding its hull sections together, say US researchers.

The authors of a book, What Really Sank the Titanic, claim the shipyard over-reached in attempting to build three new liners at once for the White Star Line: the famously opulent Titanic, which sank with the loss of 1,500 lives 96 years ago this week, the Olympic and the Britannic. Unable to find all the good quality iron rivets it needed, it eventually resorted to buying batches of lower-quality iron.

Theories about shoddy rivets popping prematurely after the ship struck an iceberg have been around for years; officials at Harland & Wolff have consistently dismissed them.

But this time the authors, both metallurgists, say they have found fresh evidence from archives in London and from the shipyard as well as from analysing rivets from the wreck.

By the first part of the last century, other shipyards had mostly already switched to all-steel rivets. Although steel was used for the central sections of hull of the Titanic, the design called for iron rivets for bow and aft sections. Most of the cracks that opened after its collision with the iceberg were in the iron-riveted forward part of the hull.

It appears that the yard, unable to find all the best-quality rivets needed, made of so-called No 4 bar, eventually settled on some rivets of No 3 bar, which is considered inferior because of greater levels of impurities, notably of slag.

In their book, Timothy Foecke and co-author Jennifer Hooper McCarty, say many of 48 rivets taken from the seabed show they contained slag. They commissioned a blacksmith to make rivets according to the 1912 specifications, of 4- and 3-bar quality. The former withstood 9,000kg of pressure under laboratory conditions, but the rivets with slag popped at 4,000kg.

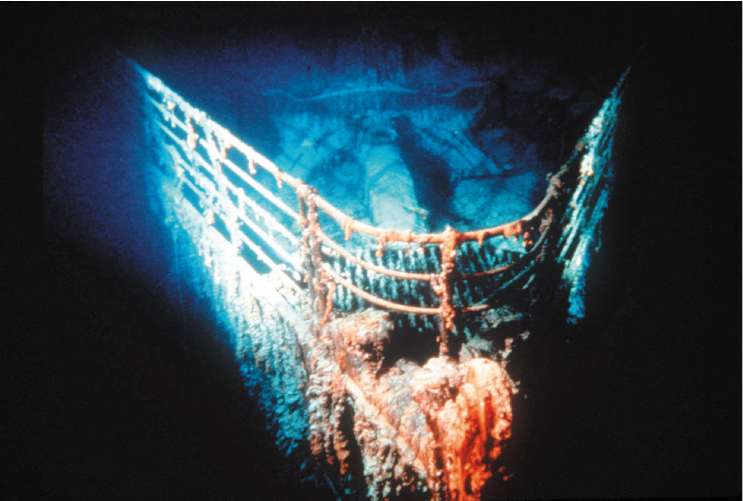

The pace of research into the sinking of the Titanic, which stands as one of the world's worst maritime disasters, picked up after the first of multiple expeditions to the wreck site in 1985. Factors cited that may have contributed to the tragedy have ranged from the frigidity of the water, the small size of the ship's rudder, which may have made evading the iceberg more difficult, and the fact that another ship in the area did not pick up distress signals because its radio had been shut down for the night.

But this latest book is likely to disturb both the shipyard and bereaved relatives because of the implication that without the alleged construction short-cuts the ship might at least have sunk more slowly, allowing for a much-diminished death toll.

A spokesman for Harland & Wolff declined to comment. He referred inquiries to David Livingstone, a retired naval architect who worked at the company for more than 40 years.

In a telephone interview, Mr Livingstone was sceptical about the findings: "All sorts of conspiracy theories come up and unfortunately the people who hold them will never change their minds. All we can ask is that the people proposing these theories show us the evidence and present it to be examined by their peers. If it is verified, so be it. But that is not the case here."

Mr Livingstone questioned in particular whether the researchers could say where exactly on the ship the 48 rivets they tested had come from. They could, he noted, have been not in the hull sections but from "secondary structures" on the vessel not designed to withstand high pressures.

But the authors say their archival research backs their contention that the shipyard was overwhelmed by the demands of building three ships at once and therefore directors were forced into compromising on quality, not only using sub-par iron but also hiring extra riveters of less certain talent.

Ms Hooper McCarty saw minutes of Harland & Wolff board meetings. "The board was in crisis mode," she said. "It was constant stress. Every meeting it was, 'There's problems with the rivets and we need to hire more people'."

Tim Trower of the US-based Titanic Historical Society, said: "This is fascinating. This puts the final nail in the arguments and explains why the incident was so dramatically bad."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments