Argentina’s painful transition: Mauricio Macri faces contentious start to his term as president

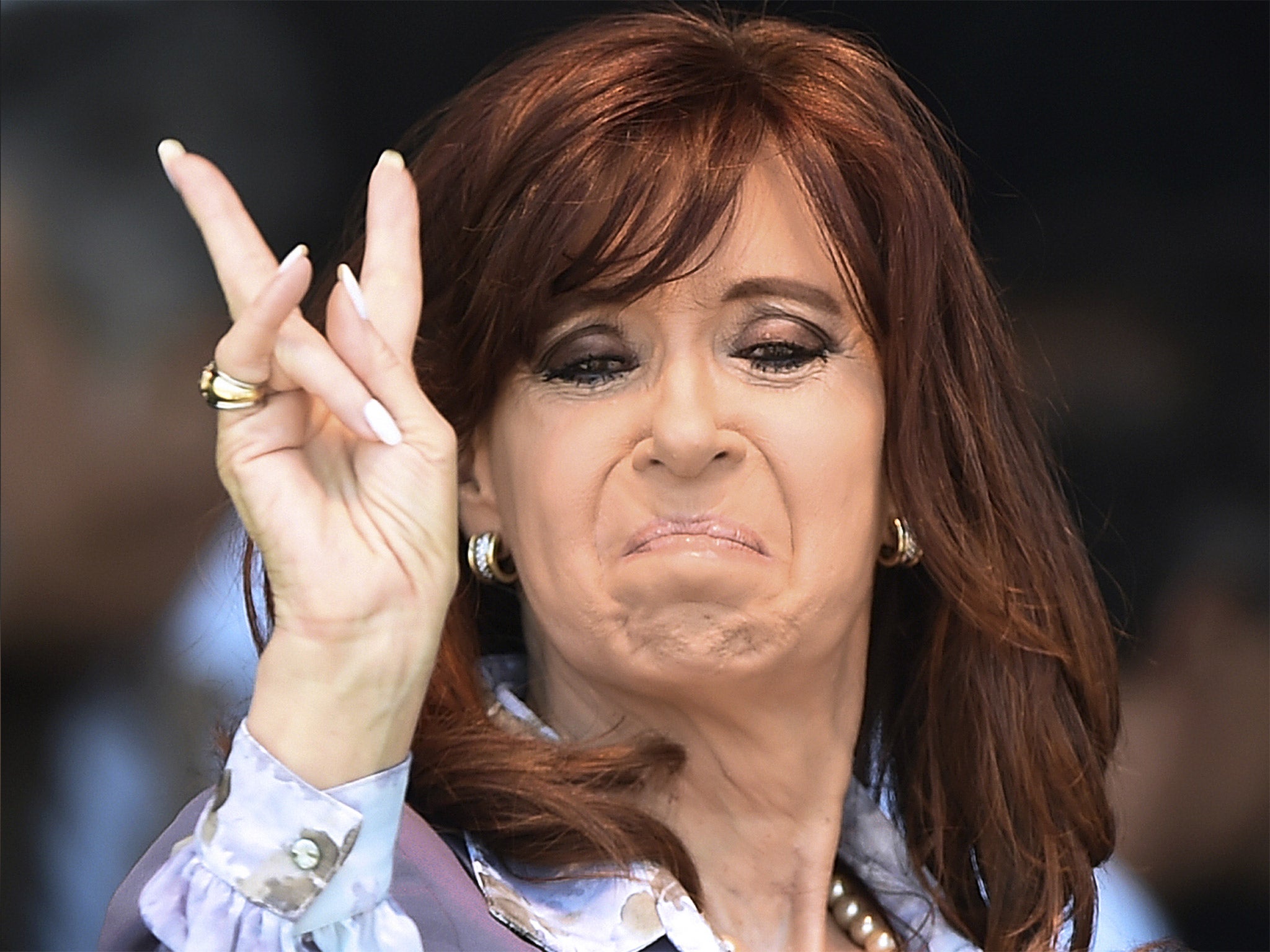

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner will not go quietly – and neither will her supporters

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Raucous backers of Argentina’s outgoing President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner poured into central Buenos Aires on Wednesday night to bid her farewell while vowing to resist sweeping social and economic reforms promised by her successor, Mauricio Macri, who will be sworn in on Thursday.

After his second-round victory last month dispatched Daniel Scioli, the ruling-party candidate, Mr Macri faces a contentious start to his term. He is only the third President since 1983 outside the Peronist movement. Its youth wing, La Campora, traditionally a key political force, has in particular vowed to block him aggressively at every turn.

Largely unanticipated at the time by the political classes in Buenos Aires, the triumph of Mr Macri, with his politically centrist and business-friendly record, comes at a time of setbacks for other leftist governments in Latin America. President Nicolas Maduro lost key midterm elections in Venezuela while President Dilma Rousseff is facing a likely impeachment trial in Brazil.

Demonstrators were crammed into the iconic Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires. Always a locus of political protest, last night it resembled a war zone, with barricades shielding both the Cathedral and the presidential palace, the Casa Rosada. The melee was both a celebration of “Cristina” and a clear expression of contempt for Mr Macri, on the eve of his taking power.

Sebastian Sanchez, 36, a member of La Campora, insisted that Ms Fernández had “protected the people” during her two terms, which followed the one-term presidency of her late husband, Nestor Kirchner. He had no enthusiasm for her successor, until now the Mayor of Buenos Aires.

“I value democracy, but he is not my President, and he is not all of Argentina’s President, and I hope he is gone within four years,” he told The Independent, hinting that Mr Macri may suffer the same fate as one previous non-Peronist President, Fernando de la Rua, who fled the country dramatically after the briefest of tenures in a helicopter in 2001.

For her part, Ms Fernández, whose record includes refusing to repay billions of dollars in debt to foreign hedge funds – or “vulture funds” as she called them – and challenging Britain repeatedly over the status of the Falklands Island, has made no effort to smooth the transition.

In the three weeks since the election, she has, in short order, appointed three new ambassadors of her liking to overseas posts and signed an emergency decree to take money from next year’s federal budget and shifting it out of Mr Macri’s hands to the provincial governors.

She also prevailed in an unseemly tussle over how today’s inauguration ceremony is going to take place. Traditionally, the President-elect is inaugurated in the presidential palace. But Ms Fernández spat in the face of protocol, causing a public fight with Mr Macri, as a result of which she has backed out of the inauguration completely.

Thus there will be no picture-perfect moment showing Ms Fernández dressing Mr Macri with the presidential sash. More than a protocol anomaly, however, the absence of that moment will stand as a symbol of the deep social and political divisions that still dog Argentina and are certain to impede Mr Macri, 56, as he attempts to enact much-needed economic reforms.

His promise of change for Argentina – economic, social and on foreign policy – is likely to prove harder to implement than his backers imagined. José Sabute, 75, a Macri supporter on Plaza de Mayo away from the Peronist crowd, says that Mr Macri has underestimated Ms Fernández. “Macri said he was going to change this and that, but now it is clear just how difficult it will be. Cristina outplayed him,” he told The Independent.

The economic challenges awaiting Mr Macri are daunting. Ms Kirchner leaves Argentina with a 7 per cent budget deficit, a rate of inflation that is believed to be around 25 per cent and assorted structural problems, not least an artificially high valuation of the national currency.

Mr Macri’s choice for finance minister, Alfonso Prat-Gay, said earlier this week that a devaluation of the Argentine peso would possibly happen as early as 14 December, entailing a lifting of existing currency controls. “The programme to unify the currency market is the first signal for the economy to start to normalise,” he told Argentinian newspapers.

Deprived of a majority in the national assembly, the toughest challenge for Mr Macri may be trying to reduce the role of the state in the economy, possibly selling off assets that the Kirchners nationalised, including the main oil company and the country’s airline.

He means also to begin unravelling the extraordinary web of social support initiatives that both Kirchners depended on to keep their base of political support. Around one in every two households in Argentina receive government support of some kind. Public sector jobs make up almost 30 per cent of all employment.

That degree of generosity was possible for a while in the mid- and late-2000s when prices for raw materials such as coal as well as soy beans were high. They have now collapsed, in part because of declining demand from China, and there is no money left to sustain the programmes.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments