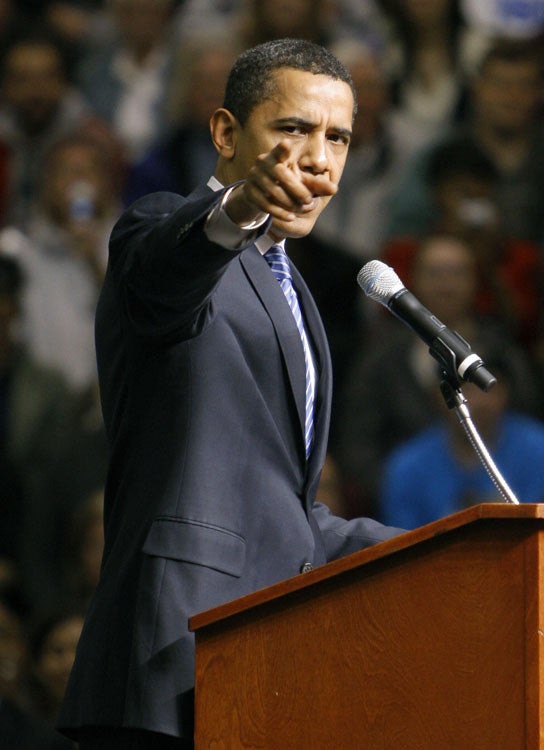

An American President: My friend, Barack Obama

As the Illinois Senator stands on the brink of the Democratic nomination, Cass R Sunstein, his colleague for 15 years, offers a fascinating insight into what makes this trailblazing politician tick

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Not so long ago, the phone rang in my office. It was Barack Obama. For over a decade, Obama was a colleague of mine at the University of Chicago Law School. He is also a friend. But since his election to the Senate, he does not exactly call every day.

On this occasion, he had an important topic to discuss: the controversy over President Bush's warrantless surveillance of international telephone calls between Americans and suspected terrorists. I had written a short essay suggesting that the surveillance might be lawful. Before taking a public position, Obama wanted to talk the problem through.

In the space of about 20 minutes, he and I investigated the legal details. He asked me to explore all sorts of issues: the President's power as Commander-in-Chief, the Constitution's protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, the Authorisation for Use of Military Force and more. Obama wanted to consider the best possible defence of what Bush had done. To every argument I made, he listened and offered a counter-argument. After the issue had been exhausted, Obama said that he thought the programme was illegal, but now had a better understanding of both sides. He thanked me for my time.

This was a pretty amazing conversation, not only because of Obama's mastery of the legal details, but also because many prominent Democratic leaders had already blasted the Bush initiative as blatantly illegal. He did not want to take a public position until he had listened to, and explored, what might be said on the other side. This is the Barack Obama I have known for nearly 15 years – a careful and even-handed analyst of law and policy, unusually attentive to multiple points of view.

The University of Chicago Law School is by far the most conservative of the great American law schools. It helped to provide the academic foundations for many positions of the Reagan administration. But at the University of Chicago, Obama is liked and admired by Republicans and Democrats alike. Some of the local Reagan enthusiasts are Obama supporters. Why? It doesn't hurt that he's a great guy, with a personal touch and a lot of warmth. It certainly helps that he is exceptionally able. But niceness and ability are only part of the story. Obama also has a genuinely independent mind, he's a terrific listener and he goes wherever reason takes him.

Those of us who have long known Obama are impressed and not a little amazed by his rhetorical skills. Who could have expected that our colleague, a teacher of law, is also able to inspire large crowds? The Obama we know is no rhetorician; he shines because of his problem-solving abilities, his creativity and his attention to detail. In recent weeks, his speaking talents, and the increasingly cult-like atmosphere that surrounds him, have led people to wonder whether there is substance behind the eloquent plea for "change" – whether the soaring phrases might disguise a kind of emptiness and vagueness. But nothing could be further from the truth. He is most comfortable in the domain of policy and detail.

I do not deny that sceptics are raising legitimate questions. After all, Obama has served in the Senate for a short period (less than four years) and he has little managerial experience. Is he really equipped to lead the most powerful nation in the world?

The United States is in the midst of a kind of Obamamania, in which a series of wonderful speeches and unexpected victories have created a storm of enthusiasm, sometimes verging on hysteria. Some people think that the fervour is thin, and could abate as fast as it has arisen. Even if it persists, the very enthusiasm that accounts for Obama's political success might have unfortunate effects on his ability to lead, if elected. It will undoubtedly raise expectations to an unrealistic degree, both domestically and internationally.

Obama speaks of "change", but will he be able to produce large-scale changes in a short time? What if he fails? An independent issue is that all the enthusiasm might serve to insulate him from criticisms and challenges on the part of his own advisers – and, in view of his relative youth, criticisms and challenges are exactly what he requires.

Fortunately, the candidate's campaign proposals offer strong and encouraging clues about how he would govern; what makes them distinctive is that they borrow sensible ideas from all sides. In this sense, he is not only focused on details but is also a uniter, both by inclination and on principle.

Transparency and accountability matter greatly to him; they are a defining feature of his proposals. With respect to the mortgage crisis and the debate over credit markets, Obama rejects heavy-handed regulation and insists on disclosure, so that consumers will know exactly what they are getting. It is highly revealing that he worked with Republican (and arch-conservative) Tom Coburn to produce legislation creating a publicly searchable database of all federal spending.

Obama's healthcare plan places a premium on cutting costs and on making care affordable, without requiring adults to purchase health insurance. (He would require mandatory coverage only for children.) Republican legislators are unlikely to support a mandatory approach, and his plan can be understood, in part, as a recognition of political realities. But it is also a reflection of his keen interest in freedom of choice.

Obama acknowledges that large increases in the minimum wage might "discourage employers from hiring more workers". It should not be surprising that in terms of helping low-income workers, he has long been enthusiastic about an approach, pioneered by Republicans, that supplements wages but does not threaten to throw people out of work. In combining concern for the disadvantaged with an appreciation of free markets, he rejects old-style leftism, and his approach sometimes overlaps with the Third Way thinking associated with Tony Blair and Bill Clinton.

But Obama is not a compromiser; he does not try to steer between the poles (or the polls). Both internationally and domestically, he is willing to think big and to be bold. He publicly opposed the war in Iraq at a time when opposition was unpopular. He favours high-level meetings with some of the world's worst dictators. He would rethink the embargo against Cuba. He wants to hold an unprecedented national auction for the right to emit greenhouse gases.

These are points about policies and substance. As president, Obama would set a new tone in US politics. He refuses to demonise his political opponents; deep in his heart, I believe, he doesn't even think of them as opponents. It would not be surprising to find Republicans and independents prominent in his administration. Obama wants to know what ideas are likely to work, not whether a Democrat or a Republican is responsible for them. Recall the most memorable passage from his keynote address at the 2004 Democratic Convention: "We coach Little League [baseball] in the blue [Democratic-voting] states, and, yes, we've got some gay friends in the red states. There are patriots who opposed the war in Iraq, and there are patriots who supported the war in Iraq."

In his book The Audacity of Hope, he asks for a politics that accepts "the possibility that the other side might sometimes have a point". Remarking that ordinary Americans "don't always understand the arguments between right and left, conservative and liberal", Obama wants politicians "to catch up with them". Rejecting one of the most intense and seemingly unbridgeable divisions in American politics, he writes of "the middle-aged feminist who still mourns her abortion, and the Christian woman who paid for her teenager's abortion". After he received an email from a pro-life doctor, Obama recalls how he softened his website's harsh rhetoric on abortion, writing: "[T]hat night, before I went to bed, I said a prayer of my own – that I might extend the same presumption of good faith to others that the doctor had extended to me."

In short, Obama's own approach is insistently charitable. He assumes decency and good faith on the part of those who disagree with him. And he wants to hear what they have to say. Both in substance and in tone, Obama questions the conventional political distinctions between "the left" and "the right". To the extent that he is attracting support from Republicans and independents, it is largely for this reason.

Obama's unusual background undoubtedly plays a significant role here. He is, after all, a child of a woman from Kansas and a man from Kenya, an African-American who spent several years being raised by his white grandparents. A former community organiser with extensive experience in the inner city, he became president of the Harvard Law Review and worked for much of his career at the University of Chicago. He knows that simple divisions badly disserve human realities.

From knowing Obama for many years, I have no doubts about his ability to lead. He knows a great deal, and he is a quick learner. Even better, he knows what he does not know, and there is no question that he would assemble an accomplished, experienced team of advisers. His brilliant administration of his own campaign provides helpful evidence here. But there is some fragility to the public fervour that envelops him. Crowds and cults can be fickle, and if some of his decisions disappoint, or turn out badly, his support will diminish. Some people think it might even collapse.

My own concern involves the importance of internal debate. The greatest American presidents benefited from robust dialogue and from advisers who were willing to say: "Mr President, your thinking about this is all wrong." Because Obama himself is exceptionally able, and because so many people are treating him as a near-messiah, his advisers might be too deferential, too unwilling to question. There is a real risk here. But I believe that his humility, and his intense desire to seek out dissenting views, will prove crucial safeguards.

In the 2000 campaign, George W Bush proclaimed himself a "uniter, not a divider", only to turn out the most divisive President in memory. Because of his own certainty, and his lack of curiosity about what others might think, Bush polarised the nation. Many of his most ambitious plans went nowhere as a result.

As president, Barack Obama would be a genuine uniter. If he proves able to achieve great things, for his nation and for the world, it will be above all for that reason.

Cass R Sunstein teaches at the University of Chicago Law School and is an informal adviser to Barack Obama

For rolling comment on the US election visit: independent.co.uk/campaign08

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments